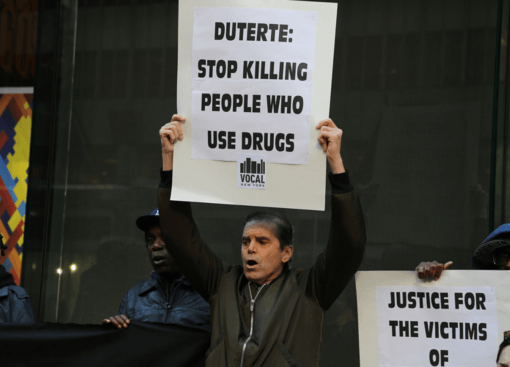

hoto by VOCAL-NY (Voices Of Com | CC BY 2.0

This week, Axios released a story revealing that President Trump privately supports the theory that imposing the death penalty upon drug traffickers will help reduce the demand for illegal drugs. This belief is flawed in several ways, but it was apparently presented to him by the President of Singapore where there is a mandatory death sentence for the crime.

In fairness, a policy novice could examine the fact that Singapore has a very low usage rate of drugs and conclude that the death penalty for trafficking is an effective deterrent. However, the results in the other countries with the same policy are far from consistent.

Harm Reduction International released the most comprehensive study on this issue in 2015. Iran executes, by far, more people for drugs crimes than any other country. There roughly 5,000 people on death row for this crime, yet Iran has one of the highest rates of opiate addiction in the world.

The opiate addiction rate of Iran is slightly surpassed by Pakistan, which also has the same policy and roughly 100 are people awaiting the death penalty for this crime. China executes the second highest number of people for drug trafficking. Their country has a fairly low rate of domestic addiction, but it is also arguably the world’s top producer of synthetic drugs, such as fentanyl, flakka, and the precursor for methamphetamine.

Overall, there are only twelve countries that treat drug trafficking as a capital offense and have available data. (Several other countries have these statutes on the books, but it is never implemented.) The majority of these countries use drugs at fairly low rates. However, when accounting for the full range of data, it is impossible to conclude that the death penalty is an effective deterrent.

Nonetheless, Trump reportedly believes that this policy has been a success in the Philippines. For one thing, the Philippines has one of the highest rates of amphetamine use in the world despite President Rodrigo Duterte’s well-publicized war on drugs. Regardless, Trump’s praise for Duterte’s anti-drug efforts is seemingly guided by willful blindness or the conflicts of interestresulting from his business dealings in the Philippines.

The Philippines doesn’t officially have the death penalty for drug trafficking. However, Duterte has supported the extrajudicial murder of suspected addicts and dealers by government forces. Human Rights Watch estimates that 12,000 people have been killed, including 4,000 victims directly murdered by the police. The others have generally been murdered by assassins working on behalf of the police. A mere allegation is enough evidence for a vigilante to earn a bounty for murder.

Duterte’s drug war is essentially a federally-approved extension of the death squad that he oversaw as the mayor of Davao. A State Department document from 2005 linked Duterte with a group known as the “Davao Death Squad,” which has been responsible for over 1,000 murders, including the bombing of a mosque and an adversarial journalist.

There is a mistaken belief that Duterte is waging this war in an earnest attempt to stamp out addiction. However, the reality is quite different as Duterte sanctioned the murder of the one person, Rolando Espinosa, who was willing to testify and name hundreds of public officials involved in drug trafficking. Unfortunately, Espinosa was murdered in his jail cell by a group of police officers. Those officers were subsequently advised by Duterte to plead guilty so he could pardon them and they’ve since been reinstated at their jobs.

Unlike nearly every other suspect in the country, President Duterte has also expected the full checks and balances of the government to protect the rights of his son, Paolo (the former Vice Mayor of Davao). Paolo is the subject of a Senate investigation involving a $161 million ship of methamphetamine from China. He is accused of protecting that shipment and Al Jazeera has reported that he’s been involved in this type of corruption dating back over a decade.

President Duterte has claimed that he would support the death of his son if he’s proven guilty. However, there’s no reason to believe he’ll allow that to happen due to his stunning record of hypocrisy with this issue. After all, President Duterte has admittedly abused fentanyl in the past. He was prescribed the drug after a motorcycle accident in 2016.

Selective enforcement has also been an issue in Saudi Arabia. U.S. government documents demonstrate that several members of the Saudi royal family participate in a drug-fueled underground party scene. Albeit, the authorities never dare to enforce the laws against the privileged elite.

Nonetheless, Saudi Arabia has the third highest rate of execution for drug traffickers. Overall, Saudi Arabia has a fairly high rate of amphetamine usage, particularly a drug known as “Captagon,” even though trafficking, along with possession, is punishable by death.

That drug has often been covered in the news reports because ISIS fighters often use it to increase aggression and stamina. On the other hand, less media coverage has focused on a Saudi prince who was arrested in Beirut in 2015 with two tons of Captagon pills.

He’s currently on trial in Lebanon, which is a far worse fate than another Saudi royal involved in drug trafficking, Prince Nayef Bin Sultan Bin Fawwaz al-Shaala. Prince Nayef was indicted in 2002 for transporting a two-ton cocaine shipment from Venezuela to Paris.

However, Saudi Arabia doesn’t have an extradition treaty with the U.S. or France and Prince Nayef has used his diplomatic ties to avoid trial. He’s an international fugitive, but he remains free in Saudi Arabia.

With that said, the U.S. government has been a catalyst for similar hypocrisy. Former Rep. Dan Burton (R-IN) wrote this op-ed in 1990 advocating the death penalty for drug traffickers. Fortunately for Burton, Congress didn’t fall in line because his son was arrested four years later for trafficking seven pounds of marijuana. He received preferential treatment from the court in the form of probation, not prison. Nonetheless, his son was busted five months later in the possession of 30 marijuana plants, but he, once again, was let off easy with a misdemeanor plea bargain.

Likewise, former Rep. Duke Cunningham (R-CA) was also a supporter of the death penalty for drug trafficking. If that name sounds familiar, he was sentenced to eight years in prison for accepting bribes from military, including prostitution services, in exchange granting cushy defense contracts. Anyhow, Duke Cunningham once pleaded to a judge for mercy on his son after he was arrested flying a planeload of 400 pounds of marijuana.

However, arguably the worst hypocrite is Donald Trump. It’s well-known that he’s conducted business with a long list of gangsters. In fact, a recent report by Global Witness found that the Trump Ocean Club in Panama was a money laundering hub for Colombian narco-terrorists.

Worst of all, this new affinity for executing drug trafficking is seemingly one of many affectations that Trump has embraced to brand himself as a strong leader. Keep in mind, Trump adamantly supported the legalization of drugs, long before he made a serious run at the presidency.

In 1990, Trump asserted to an audience at a luncheon of The Miami Herald, that our country needed to end the war on drugs. “You have to legalize drugs to win that war,” said Trump. He also pointed to the core of the issue; our politicians lack the “guts” to make the necessary changes.

Brian Saady is a freelance writer whose work covers a variety of topics, such as criminal justice, corruption, and foreign policy. He’s also the author of four books, including two that directly criticize the war on drugs. The titles are The Drug War: A Trillion Dollar Con Game and America’s Drug War is Devastating Mexico. You can follow him on Twitter and check out his website.