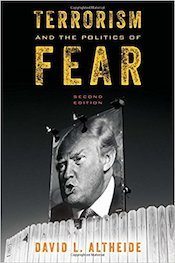

Recovering from President Trump will require planning. After the allied assault on North Africa in 1942, Winston Churchill remarked: “Now, this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” In ordinary times, the end of one presidency does not signal a fundamental shift for new leadership. These are not ordinary times; Donald Trump has systematically negated significant domestic and international policies, programs, and treaties. And now he has openly attacked the F. B. I. and the Department of Justice by releasing a memo scripted to make himself look good. It is reasonable to assume that Mr. Trump will not serve another term, whether due to intervention during the next three years for obstruction of justice, treason, or simply not be reelected. Journalists, opponents, Republican Party leaders, as well as strategic leaks from many of his own advisors and cabinet members make it clear that his disjointed policies, statements, and executive orders are slogging down in narcissistic muck. His aftermath may be just ahead, but there must be a strategy for U. S. leadership going forward. I am not referring to particular Presidential candidates, but rather to strategic healing, maintaining, reassuring, and rebuilding domestic and international alliances. There are several parts to this recovery that I have examined in my recent book, Terrorism and the Politics of Fear.

First, key organizations and institutions should join in a well-publicized national and international communication campaign to convey their commitment to key American values including equality of opportunity, non-discrimination and equal rights for women, racial, religious, and ethnic minorities, support for science and international treaties, as well as diplomatic solutions to major world problems. Key organizations should come together at a national summit meeting and issue a statement with several key points about the significant national and world issues, stressing that the majority of people in the United States—who, after all, voted against Mr. Trump—affirm a commitment to the major principles. The aim is to assure the significant groups, regions, and countries that positive steps will continue and to persevere until Mr. Trump leaves or is forced from office. The relevant organizations should include, but not be limited to, religious groups (e.g., the National Council of Churches), organized labor, the National Academy of Science, the United Nations, NATO, The European Union, major energy organizations (e.g., Sustainable Energy Organizations), International Atomic Energy Agency, and the International Court of Justice.

Second, we must understand the role of the mass media and propaganda in promoting an entertainment based politics of fear that led to the election of reality-TV star Donald Trump, who  benefitted from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The war in Iraq was partly the result of an expanding politics of fear, or decision makers’ promotion and use of audience beliefs and assumptions about danger, risk, and fear in order to achieve certain goals. Prior administrations promoted fear of terrorism and offered more social control and military operations that launched 15 years of invasions of Middle Eastern countries, sent hundreds of unmanned drone attacks that killed thousands of civilians, launched an epoch of governmental surveillance and propaganda that systematically frightened and angered millions of Americans to such an extent that they elected Donald Trump, who vowed to prevent Muslims from entering the United States, attack immigrants, and support hate groups.

benefitted from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The war in Iraq was partly the result of an expanding politics of fear, or decision makers’ promotion and use of audience beliefs and assumptions about danger, risk, and fear in order to achieve certain goals. Prior administrations promoted fear of terrorism and offered more social control and military operations that launched 15 years of invasions of Middle Eastern countries, sent hundreds of unmanned drone attacks that killed thousands of civilians, launched an epoch of governmental surveillance and propaganda that systematically frightened and angered millions of Americans to such an extent that they elected Donald Trump, who vowed to prevent Muslims from entering the United States, attack immigrants, and support hate groups.

Third, we must challenge the insidious effects of media culture promoting the politics of fear. The politics of fear is relevant for social life because it influences our activities, meanings, routines, and perspectives. These effects can be reduced through critical thinking and awareness of the social changes and the implications of blanket adjustments in security and policy. The initial step is to expand awareness of the role of media logic in social life, and the ways in which new information technologies have altered citizen awareness, political campaigning, and propaganda manipulation. This is especially challenging in our time of social media that are instantaneous, personal, and visual. Fake news and propaganda can only survive when users cannot think critically and are oriented to accepting brief, emotionally resonant messages.

Fourth, another important step involves journalism training, ethics, and responsibility. With the explosive growth of fake news by propagandists—Russians included—journalists must become more critical and bold in refusing to report on blatant lies, or at least greatly qualifying the fallacious claims. More time and space needs to be given to reports in order to provide more contexts to understand the meaning and significance of events and counteract the destructive simplicity of propagandized memes. This includes journalistic reflections on coverage and narratives of prior events as things become clearer over time. Mistakes and errors should be acknowledged.

Fifth, we must recognize that very little of any consequence occurs in our society without popular culture. This is important to defuse harmful stereotypes, especially simplistic assertions about stronger social control to protect us from danger. What we call things matters more than ever, particularly when politicians of fear seek more control by attacking safeguards of individual liberty and dignity.

Sixth, public civility is critical to protect individual freedoms. I suggest that we continue to pursue international tribunals for redress against the illegal actions of the United States and others. Tyrants and madmen are not solely to blame for their mayhem; the challenge is to prevent crowds and voters from following them. Donald Trump’s election cannot be blamed on him; 63 million people voted for him, so we must understand how so many presumably decent people could condone rants that were racist, bigoted, discriminatory, and were also dismissive of basic scientific findings about critical developments such as global warming.

Finally, we should inform our students and citizens about a wide range of media literacy. We must tell the young people about another way, about the implications of social control and bad decisions. In addition, scholars and researchers of all persuasions should attend once again to the subtle forms of propaganda, deviance, and resistance. The foundation of this moral reasoning must be citizenship and civil rights, in addition to individual responsibility. In our endeavor, let us not become what we’re trying to undo, let us not forget how moral absolutism and entertainment got us to this point. Above all, we must continue to tell our students and whoever will listen to be aware of the propaganda project, but to not be afraid.

The politics of fear has taken a toll on American life far greater than the normalization of massive surveillance and a herculean increase in the defense budget. While it is a cliché to argue that we are a product of a our past, it is instructive to make specific connections with decisions, policies, and especially the role of propaganda and the politics of fear that have helped set the 21st century agenda. To put it most directly, little of our misguided romp through the mushy quick sands of terrorism would have occurred without the misinformed stumbling into Afghanistan and Iraq that expanded the politics of fear and heightened Americans anxiety about the future. These steps can help us to begin the end of President Trump’s American disaster.