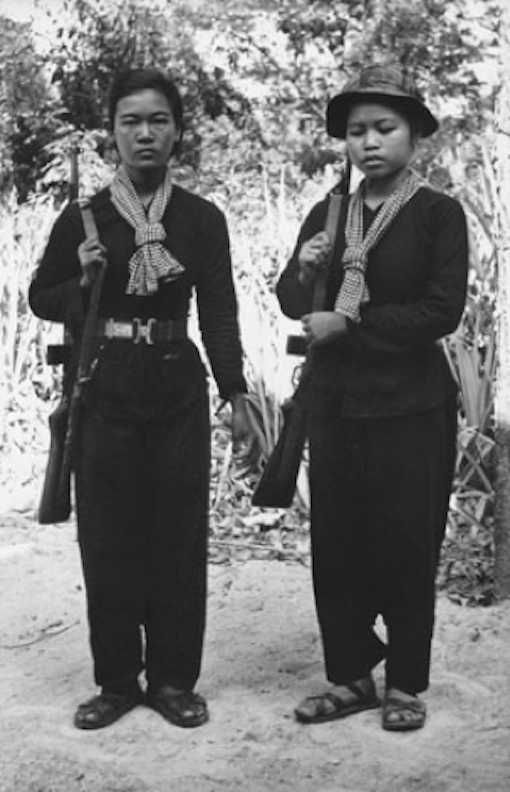

Guerilla girls, 1964-65. Photo Wilfred Burchett.

To mark the 50th Anniversary of the 1968 Têt Offensive, CounterPunch is serializing Wilfred Burchett’s Vietnam Will Win (Guardian Books, New York, 1968) over the next few weeks. Readers can judge for themselves the validity of the facts, observations, analysis, conclusions, predictions and so on made by the author. The books is based on several visits to the Liberated Zones controlled by the National Liberation Front (‘Viet Cong’) of South Vietnam in 1963-64, 1964-65 and in 1966-67 and close contacts with the NLF leadership, resistance fighters and ordinary folk. Wilfred Burchett’s engagement with Vietnam began in March 1954, when he met and interviewed President Ho Chi Minh in his jungle headquarters in Thai Nguyen, on the eve of the battle of Dien Bien Phu. He was also on intimate terms with General Vo Nguyen Giap, Prime Minister Pham Van Dong and most of the leadership of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam during the country’s struggle against French colonialism and American imperial aggression. Wilfred Burchett was not writing history as a historian, with the benefit of hindsight, access to archives etc. He was reporting history as it was unfolding, often in dangerous places. He was an on-the-spot reporter, an eyewitness to history. In his reporting, he followed his own convictions, political and moral. The book he wrote after his first two visits to the Liberated Zones, Vietnam: Inside Story of the Guerilla War (International Publishers, New York, 1965) concludes with this short sentence: “The best they [the Americans] can do is to go home.” Vietnam Will Win confirms that.

Unfortunately, it took another seven years (1968-75) of death and devastation – and the extension of the war into Cambodia and Laos – for the U.S. to finally leave Vietnam in ignominy in April 1975. So here, chapter by chapter, Wilfred Burchett exposes the futility of fighting a people united in their struggle for independence, liberty and unity. It also explains, soberly and factually, why they were winning and how they won.

George Burchett, Hanoi

Winning Hearts and Minds

If there was one matter on which all Americans in South Vietnam were virtually unanimous at the turn of the 1967-68 year, it was that “pacification” was still a failure. Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker and his CIA-trained deputy Robert Rower could cite statistics of “Vietcong” killed by body count, miles of roads opened and bridges “secured”; acres of rice land taken out of “Vietcong” control; the fact that elections had been held; an increased number of “defectors” under the “open arms” program – and add all this up to get a total of progress. But even the most optimistic of the official U.S. propagandists admitted that victory in the decisive battle for the “hearts and minds” of the people was more remote than ever and this knowledge permeated all the end-of-the-year survey articles of the Saigon correspondents.

Even Hanson Baldwin, military editor of the New York Times, who strained facts and the indulgence of his readers to the ultimate degree to present an optimistic picture of the military situation, wrote after one of his rare visits to South Vietnam: “Most authorities agree that the job of eliminating the underground government and terrorist apparatus in South Vietnam, and of what amounts to nation-building, is just starting, that it has made very limited progress…” Baldwin tries to comfort his readers by adding that this job “now appears to be on the right track” but “none are hopeful that it can be accomplished quickly.”[1]

This was after over 13 years of a United States shadow government in South Vietnam, after six years of direct U.S. military intervention in all-out war against the NLF guerrillas and after almost three years of massive intervention, with U.S. “advisers” running administrative affairs from the ministerial level down to civil affairs officers at provincial and district level.

How is it possible that the expenditure of unlimited billions of dollars and the unrestricted use of the most complete and efficient repressive machinery ever conceived have not prevented the NLF from winning the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people? It was because this battle was won by the NLF years ago, and the U.S. counteroffensive has never been able to reverse the decision. How do you go about winning hearts and minds when you have neither dollars nor guns, or at least very few of the latter? The official U.S. answer is that it was done by “terror,” and it is not by accident that Baldwin refers to the “terrorist apparatus” which has to be eliminated. And terror – l prefer the NLF term “revolutionary violence” – has been an element in the NLF success in winning the hearts and minds of the people, especially in the darkest days of the Diem dictatorship when for a time, police control was nearly total and any district chief had complete power of life or death over every single person within his administrative competence. It was violence selectively applied that brought the first rays of hope, just as it did in the blackest days of Nazi occupied Europe when a French patriot assassinated a notorious Gestapo agent. Violence has been used selectively to wipe out, usually after repeated warnings, some of the worst local tyrants, with a most salutary effect on his deputies or successors in almost all cases.

In an earlier book[2] I had mentioned the execution of a certain Chan, who headed Ngo Dinh Can’s secret police[3] in the three north-central provinces of Quang Ngai, Quang Nam and Binh Dinh. In Chan’s safe, a bag was found containing 432 human ears, in each case the left ear stapled to a document giving the owner’s name and a receipt for 5,000 piastres. The right ear had been forwarded to Can’s headquarters as proof that the victims, former resistance cadres, had been killed, and for each one Chan received 5,000 piastres. So violence or terror was visited upon Chan on May 18, 1960, by an “armed propaganda group.” His body was left on the road with a piece of paper stuck to it explaining who he was and why he had been executed. This was one of many similar acts undertaken at that time, before the National Liberation Front had been formed, by local patriotic groups determined to “break the grip” of the enemy, as the cadre who executed Chan later explained it to me. A list was found in Chan’s office of several hundred former resistance members marked down for liquidation, as well as the names of a network of Chan’s agents. The intended victims were immediately warned, one or two more of the worst of Chan’s agents were killed and the rest warned to cease their activities or else…

Following the publication of my account of Chan and the filed ears, I had a visit from a U.S. Information Service agent from Saigon, Dr. Milton Sachs, who protested that the story could not possibly be true. Neither the American “advisers” nor Ngo Dinh Can, who was not at all the bloodthirsty tyrant that I had depicted, according to Sachs, would ever have permitted such practices. The “lie about the filed ears invalidated the whole of my book.” In connection with this official indignation, it is interesting to quote from a passage of the interrogation by the French lawyer, Gisèle Halimi, of witness David Tuck[4] at the second session of the International War Crimes Tribunal:[5]

Halimi: The ears of Vietnamese, for certain Montagnard tribes, are reputed to be valuable. Can you confirm instances of American bounties paid for Vietnamese ears?

Tuck: Well, as for the cutting off of ears – when I was over there it was a practice of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, after a battle, to cut the ears off of dead Vietnamese and to use them as souvenirs. Also this was a practice of the 25th [U.S. infantry division]. This was more or less a passing fad. The person who had the most ears was considered the number one Vietcong killer and also when we would get back to base camp, the one who had the most ears would get all the free beer and whiskey they could drink. It was more or less a passing fad, but they did cut the ears off of dead Vietcong to show as souvenirs.

The execution of Chan was a typical example of violence used to strike some sparks of hope in the hearts of people against whom unrelenting terror was being applied every day. It was a case of revolutionary violence being employed to break or at least weaken a veritable reign of terror. The lives of several hundred patriots were saved by that one act, and for a time at least there was a marked falling off in the repressive activities of the Diem police in the provinces concerned. But violence employed against the enemies of the people was only one element in gaining support for the revolutionary resistance struggle.

The aims of the NLF reflected the aspirations of the overwhelming mass of South Vietnamese people. But how could ordinary people in those first years of insurrectionist activity really know that this was so? After years of unrelieved terror, how could they have any faith in the small groups that started to turn up, agitating for a nationwide insurrection? How could they believe they were sincere, let alone that they had any chance of success? They might very well be Diem agent-provocateurs sent to find potential resisters. And indeed, often agents would use all sorts of revolutionary phrases to deceive the gullible and mark them down for later arrest. In the 1954-59 period, the Diem police began registering, then tracking down and finally arresting and liquidating all those who had taken part in the anti-French struggle. Practically the only way for former resistance cadres to survive was to flee to the jungle and mountains, or in any case to escape from their native district. To return to the police-ridden “strategic hamlets” to make the first contacts and to try to win the confidence of the people was an extremely difficult task. In studying the accounts of revolutionaries fighting in the mountains and jungle of Latin America, it is clear that the first contacts with the plains-dwellers are almost always a major problem. The objective situation of identity of interest between the aims of revolutionaries and the aspirations of the people remains a theoretical concept until contact is made and cemented.

Nguyen Mau, 53 years old when I met him, with a deeply lined face and muscled arms and legs, was an NLF cadre from Huong Tra District in Thua Thien Province, of which Hué is the capital. He was one of those who had played a role, “rather a prominent cadre,” he said, in the anti-French resistance war. “When the Diem police started hunting us down, I had to go into hiding. Not a single former resistance cadre was spared in our province, except the few of us who fled to the mountains. In 1955-56 we could still move around and carry out secret agitation for the elections, which were supposed to be held in July 1956. After Diem carried out the referendum that year making himself head of state, the repression was even more severe. Contacts became more difficult and we hesitated to subject the population to reprisals by continuing to meet. By 1959, with the introduction of Law 10/59,[6] we could have no contact with the people. Law 10/59 was posted up in big letters on bulletin boards everywhere. Anyone suspected of even the slightest sympathy with the former resistance movement, or of even the slightest opposition to the government, was dragged off under Law 10/59. Repression went hand-in-hand with some demagogic maneuvers to try to persuade people that the Diem regime was interested in their welfare. For instance, they confiscated land which we had distributed during the resistance period – Huong Tra was a liberated area then – and said that one-quarter of this was being put aside for rebuilding churches and pagodas, so people could benefit from religious services. The rest they handed out to Diem “trustees” for “services rendered.” They built roads and bridges, and people with houses alongside the main highway were ordered to repair and paint the outside to present a facade of prosperity. No matter how poor, people were forced to do this; if they could not raise the money, they were automatically considered ‘vietcong’ and were dragged off. Night and day the theme was drummed into people that they should forget the Vietminh for all time.

“At the higher level, repression was carried out by the paramilitary organs and secret police of Diem’s administration. At lower levels, by the chiefs of the ‘self-defense’ units. The people were crushed between these two levels of repression. Within the communities there was the ‘neighborhood mutual information’ organization for mutual espionage, one such unit for every five or six families, with one elder responsible for reporting any movements, visits or suspicious conversations. The elder had to be able to account for the whereabouts of every member at any moment the authorities demanded. The presence of any stranger had to be reported immediately. Control was so close that it was impossible for us cadres to live among the people. But we came down from the hills at night to try to make contacts. If the people were really voluntarily under the thumb of the Diem authorities, we would not have lasted long. But they remembered the resistance years and stood by us. They found means of providing food for us, [which was] a difficult problem in the mountains.

“In those days you could say we were ‘based’ in the mountains, but these were ‘bases’ for survival. We had no arms at all and barely the means of existence. All adults in the ‘strategic hamlets’ had to be provided with sticks, ropes and lanterns – ready to attack, seize and tie up any stranger. They had to make a noise, beat gongs or pieces of wood, shout at the top of their voices ‘vietcong’ and rush out with torches. They would do this when one of us turned up, but invariably they would fall over each other, a dozen voices crying at once: ‘He has gone this way… No, that way’ and shouting in all sorts of directions but the real one. But 1957 to 1959 were very bad years for even those cadres who had escaped Diem’s police net. We could just about keep alive, but could not do much for the revolution. It was difficult to know what was the political line from above, so that even if with tremendous difficulties we could make contact with the people, we could give them no clear guidance. In the first two years at least the line had been clear: to push for the loyal fulfillment of the Geneva Agreements leading to the 1956 elections. But once the elections were sabotaged and Diem and the Americans openly turned their backs on the Geneva Agreements, we were rather lost. We could keep alive and that was about all; leave a scrap of paper in a field in exchange for a packet of food.

“Late in 1959, when former resistance leaders got together and decided to start armed resistance, our task was to try to establish political bases in the villages. We thought it would be very difficult after all the repression and anti-‘Vietcong’ indoctrination. But in fact we were received most warmly. The people had missed us for so long, their sufferings had been so great and there seemed no way out, no ray of light anywhere, until we came back. We explained the new line, at first on a very small scale, to an individual here and there. It was forbidden for two persons to speak together, even brothers… Under those circumstances it was long, patient work. But with one or two contacts in each village, we could move in at night, paint up a few slogans, leave some hand-printed leaflets, above all let the people know of our presence.

“It was necessary to know the people’s reaction to this, that of the intellectuals, and also that of the enemy – Diem officials. We quickly found that the masses of the people were delighted and the Diem tyrants were impressed. As a former liberated area, many of the latter knew of the great prestige of the Vietminh. A typical reaction was: ‘Ah, so the Vietminh is still around. They didn’t all go to the North after all.’ And so with our first modest measures, a slight tremor of fear ran down the spines of the tyrants. Some of them started justifying themselves to the people: ‘We are not really bad. We have to act the way we do because of orders from above, it’s not that we want to.’ Of course,” Nguyen Mau added, “if our activities had been restricted to one or two hamlets only, the enemy would have concentrated his forces and caught us, wiping out our fragile political base. But by the time we started scrawling up slogans and leaving leaflets, we could do it in many hamlets simultaneously.

“By 1961, after the NLF was founded and we secured arms for our ‘armed propaganda groups,’ we had been able to punish some of the worst of the tyrants and when we left leaflets there were flags and banners of the NLF as well. If, at first, it was only the most stouthearted who worked with us, the appearance of flags and banners and then printed leaflets gave fresh heart to everyone. ‘We feel we are nearing the day when our children will meet their fathers again,’ was how one woman expressed it in those early days. By then it was clear to everybody that with the peaceful, political struggle which had been our previous line of action, we would get nowhere. We started a combination of legal and semi legal action. There were mass actions from the hamlets, with people marching to the district headquarters carrying petitions for ‘freedom of movement’. This was not only a question of petition, but by the act itself a certain ‘freedom of movement’ had already been wrested from the authorities. The young people showed a militant spirit when the police and local authorities tried to halt them.

“With the growth of this feeling we were able to transform the enemy’s organizations into our own. After all, the parents of those in the ‘Republican Youth’ were peasants, our own people. Under our influence they started working on their sons and on others within the so called ‘self-defense’ units. These became our organs; they seemed to be in the service of the enemy but in fact they were protecting us, informing us of enemy plans.

“During 1961 at the appeal of the Front, there was a nationwide insurrection and armed struggle became widespread. The enemy started to ‘conscript youth throughout the countryside, every able-bodied man from 18 to 35. Parents wanted their sons in the NLF, not in the Diem army, and the young people were pleading to join us in the mountains. But if they just took off there would be reprisals against the parents. So in one village they asked us to stage an attack. We did this, making a sham attack. It was the first armed action in Huong Tra District. We came with troops, made a lot of noise, used our loud speakers, held a public meeting and then left; most of the young men left with us. The local authorities carried out reprisals against some parents denounced by Diem agents for having collaborated with the attackers. So word was sent for us to come again and deal with some of the most active agents, of whom five were listed. We attacked again one night, captured the agents, killed one and warned the others.

“This was repeated in hamlet after hamlet; the worst of the agents, those responsible for the deaths of several people, were killed. And it was always explained why the particular tyrant was executed. At this period the mass movement became much more active. People started ignoring the most repressive regulations; they started setting up all sorts of organizations as a pretext to get together, some of them quite curious. For example, there were ‘Burial Associations’ for pooling money to ease the burden of funeral expenses in case of death of a family member; and ‘Pig-Slaughtering Associations’ for carrying out an old habit which consisted of a group of families killing pigs in rotation and sharing the meat since one pig for a single family was too much. The Diem authorities tried to suppress such associations, but they were made to look very ridiculous, and the local officials were frightened anyway and winked an eye at lots of things for which people would have been arrested, tortured or at least imprisoned a few months earlier. Although in appearance mutual aid associations, they were political [groups]; they were covers for getting together and organizing all sorts of activities.

“In 1962, Diem opened a new conscription drive and youths started leaving on their own to join us in the forest. When the parents knew they were well away, they reported the fact to the authorities. ‘Our sons went off into the forest to get firewood and never came back. Maybe the Vietcong kidnapped them; you should go and get them back. Or maybe it was you who conscripted them into the government army. Anyway we want them back.’ And they also used this pretext to march out of the ‘hamlets’ to district headquarters to protest. By the end of 1962, this was a general situation throughout the whole province, with the exception of a few villages in the immediate outskirts of Hué and the city itself. We had the women, youth, old people, even children organized, wresting back bit by bit all sorts of democratic freedoms. Although we had no organization inside Hué, news of what was going on was well known among students, intellectuals and Buddhists. Copies of our leaflets and NLF banners were smuggled in, news of certain of our exploits was passed around by word of mouth. We had our listening posts there, and ‘the Vietminh is still around,’ was a current phrase in Hué by the end of 1962. Sometimes we were helped by accidents.

“Once we badly needed some cloth for uniforms. We were tipped off about a truck that was carrying just what we needed. We laid an ambush, halted the truck and piled the goods up on the road, assessing the value. Then we found we had forgotten the money. We piled everything back on the truck and sent it on its way into Hué. The truck driver and his passengers soon spread the word and in the marketplace we picked up the reaction: ‘These Vietcong are not bandits. They are very honest, not like the Diem troops who seize whatever they want.’ ”

The rest of Nguyen Mau’s account followed the classic pattern of a gradual transformation of the political struggle within the “strategic hamlets” into armed struggle. In 1963 the inmates themselves in coordination with the guerrillas staged uprisings, dealt with any Diem agents or troops who offered opposition, tore down the barbed wire fences and went back to their native villages and rice fields and the tombs of their ancestors. Attempts to round up people and to re-concentrate them only increased the scope of the armed struggle. Even if the period of liberty was at times brief, the flames of struggle had been kindled and could not be quenched until the whole “strategic hamlets” system had been dismantled following the coup which ended the regime and lives of the Ngo Dinh brothers. What Nguyen Mau related was typical of scores of other accounts I gathered from cadres who carried on that patient, difficult work of establishing contacts and stimulating action, and also from former inmates of the “strategic hamlets.” The general picture was the same as depicted by Nguyen Mau. Once the initial difficulty of establishing contacts was overcome, the first few propaganda acts carried out and confidence established, mass political activity soon followed, and political struggle was inevitably transformed into armed struggle. But the work of Nguyen Mau and the handful of cadres who worked with him was greatly facilitated because the districts of Thua Thien Province in which they operated were former liberated areas, where memories of the Vietminh administration and its land reform policies were still fresh and where the people naturally went back to their old wartime organizations of the first resistance.

What happened when the Saigon army came out in force? And in regions which had not been liberated in the first resistance? Le Van Chien, another veteran cadre from Tien Phuoc District of Quang Nam Province, explained: “We had not been able to set up a guerrilla base there because enemy control was too thorough. It was only in early 1963, when our armed forces were fairly strong, that we could move down to liberate Tien Phuoc. At first people showed some reserve because they had been in the grip of the enemy for a long time. They also feared that the NLF forces would be there for only a short time, and they would be defenseless against reprisals once we left. Before we made any move, our political cadres tried to explain our policies. But the first time our forces approached a village, they found only old people and children. The able-bodied were afraid and fled with their livestock and whatever they could carry. We stayed around, looked after their property and did a bit of field work, cleaned up the houses, bathed the children and told them stories. The others sent back some scouts and when they reported back on how our men behaved, everybody returned. They were very impressed with what we had done and started to listen to our explanations, and to what had been done in Thua Thien and other provinces. The enemy was afraid to move while we were around, as we had a fairly strong force and we knew that the provincial commander thought we were even stronger. Our cadres had spread plenty of rumors in the marketplace.

“Within a couple of months we had liberated almost every hamlet in Tien Phuoc and had set up mass organizations, including self-defense units which set traps around all the approaches to the hamlets. When the various organizations were consolidated, we pulled out to liberate other districts.

“In March 1963, soon after we left, the provincial command sent two regular army battalions, two battalions of regional troops, an armored car unit and 57 ‘self-defense’ troops on a sweep through a district of which the total population was 15,000. When they entered the first hamlet, they saw over the main entrance big signs: ‘Down with the U.S.-Diemists,’ ‘Government Soldiers Should Not Shoot Their Own Compatriots.’ The hamlet was deserted except for some old people. Everyone had gone off to the jungle. They asked one old man: ‘Who wrote those signs? It must have been your friends, your relatives.’ ‘No,’ replied the old man ‘they were written by the NLF fighters.’ They arrested the old man and ordered him to lead them to the Vietcong. But the old man said: ‘Arrest me if you like, but I don’t know what the Vietcong are. Your Republican Army is much stronger than the Vietcong. But when they entered the hamlet yesterday, your troops were not here to protect us. Why weren’t you here yesterday when the hamlet was full of Vietcong troops? Now it is full of your troops. You see the slogans they stuck up everywhere. If you had been around they would not have dared. But you came after they left. And they have taken everyone with them. Maybe they went to another village, or maybe in the jungle. But I’ll give you a friendly warning. Don’t wander around the houses or fields; the Vietcong have stuck traps around everywhere. I don’t dare to move myself.’

“The old man was released and the troops took off for another hamlet. The same thing. Only old people left. They asked a woman of 60 where the Vietcong were. She said they had come the previous day but had now left. The officer in charge was very angry and demanded that she lead them to wherever they had gone. She invited him and one or two others into her home to drink some tea, saying she would explain everything. After some muttering a couple of them accepted. ‘Yesterday a lot of Vietcong entered our hamlet,’ she said. There were very many of them and what could we do? They had lots of heavy guns. What sort they were I don’t know, but they had a lot of guns so big that they needed several people to carry them. They only left here 10 or 15 minutes ago and they forced everyone to go with them and help prepare an ambush for your troops.’ ‘Where? Where?’ demanded the officer in charge. ‘I don’t know because I was afraid and hid until everyone had left.’ The officers were very excited by this time and shouted ‘Is this true?’ The old woman said: ‘You can see for yourself there is no one here. I don’t know whether they have really prepared an ambush but that’s what they said.’

“The officers muttered among themselves that if they had ordered the villagers to prepare an ambush, this meant the Vietcong would probably take the initiative in a surprise attack, so they decided to withdraw. They told the old woman: ‘While the Vietcong are too close to the villages we want to avoid any open clash because too many villagers would be killed. For the moment while they have a strong force here, it is better to obey the Vietcong, but in your hearts you must remain loyal to the Government.’ And with that they pulled out. The old woman hoisted an agreed ‘all clear’ sign and the villagers came back for a hearty laugh over the fact that the words of an old woman could force the retreat of an enemy battalion.

“What we quickly found was that once the enemy knew the local people had been mobilized by the NLF they moved with the greatest caution. After the people rise up the first step is to do away with the most notorious of the agents, which means the enemy has no eyes, ears or tongues. The enemy’s usual tactics were then to circle around the villages, burn down isolated houses, destroy crops and any animals they found, but to avoid groups of peasants like the plague. In this particular incident, it was corn harvesting time, so the expedition turned into a corn destroying operation. They destroyed as much of the harvest as they could and then withdrew, but even without any shots fired they had quite a few casualties from the spiked traps. The fact that they tried to destroy the harvests was in itself an admission of defeat. They could not reestablish their administration. Land reform had already been carried out, self-defense units had been set up and Tien Phuoc District, which is in the plains, became a springboard for liberating other districts in northern Quang Nam.”

In many cases, of course, the Saigon troops could not be “talked out” of a fight and there were very severe clashes in which the “self-defense” forces often had their first baptism of fire within a few days of being established. But in very many cases head on clashes were avoided by the high level of political consciousness of the villagers and carefully thought-out political and propaganda tactics which were applied with infinite skill, courage and ingenuity. The decisive factor was that the overwhelming majority of the people welcomed the NLF forces in whatever form they came, once they were convinced that they really meant business. And when the abolition of the detested “strategic hamlet” system got under way there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that they really did mean business.

“When we take over a village,” Le Van Chien explained, “we ask people to bring everything related to the Saigon regime, photos of Diem and American bigwigs, banners and flags, etc., into the village square and burn them. This has a big political effect. We virtually never attack unless the political base inside has first been prepared. We always know who are the worst enemy agents and these are arrested. We get the villagers to nominate their own administration and then encourage them to confiscate the land of the worst of the agents and any absentee landlords, distributing it to the peasants, starting with the poorest. This creates a good atmosphere from the start. We announce, in the name of the Liberation Front, the abolition of all taxes and debts and that rent will be reduced following discussions with any local landlords still around.

“We announce an amnesty for the families of agents, even of the worst of them. We make a point of never touching or even accusing the family members. Volunteers are accepted into the self-defense corps and we usually give them a few weapons to start them off, and before our forces leave, we show them how to manufacture arms and prepare traps. We explain that the new local administration is an organ of the National Liberation Front, not linked to any central administration, competent in local affairs only. Some of the people are usually a bit scared as to what may happen when our forces pull out. They worry that their weapons are not sufficient, but we explain that what is decisive is their political viewpoint, their unity and solidarity, and theirs is not an isolated case. Also, we explain that our armed forces will always be somewhere in the area. When they realize they are part of a huge movement sweeping the countryside, then even the most timid gain confidence. We help them to start up their vegetable gardens and orchards again, help them to dig fish ponds, plant bamboo and trees, build pigsties and chicken mops and recreate the sort of physical surroundings they had before they were herded into the ‘strategic hamlets.’ The new administrative committee immediately forms subcommittees for education, public health, economic affairs, defense and security, and people really feel they are running their own lives.

“After our cadres or our forces have liberated a village and helped the people start rebuilding their new life,” concluded Le Van Chien, “no matter what trials and sufferings they might have to endure later, their hearts and minds are with us forever. This is proven in thousands of ways every day. Even if the enemy deploys great force and temporarily reestablishes his control, the people remain with us and even under the most difficult conditions they find means of letting us know this.” Le Van Chien’s assessment was undoubtedly correct and this is the insuperable obstacle that America’s best generals and diplomats are unable to overcome.

The battle for hearts and minds has been lost by the United States and the extent of this defeat became clearer as hostility broke out into the open w U.S.-Saigon occupied territory in late 1967.

Notes.

[1] Printed in the International Herald Tribune (Paris), Dec. 27, 1967.

[2] Vietnam: Inside Story of the Guerrilla War, International Publishers, New York, 1965, pp. 142-143.

[3] Ngo Dinh Can, the third of the Ngo Dinh brothers to have been killed following the coup in which Ngo Dinh Diem and Ngo Dinh Nhu were murdered. Can, who reigned supreme in Central Vietnam, was a medieval type of sadistic, brutal tyrant who took pleasure in personally torturing his victims before he executed them. He took refuge in the U.S. consulate at Hué after the anti-Diem generals’ coup. He was later handed over to the Saigon authorities, who tried and executed him for his bloodthirsty excesses. His victims had included numerous army officers.

[4] Private (First class) David Tuck served in South Vietnam with A company, 1st battalion, 35th infantry regiment of the U.S. 25th Division, from January 8, 1966, to February 9, 1967.

[5] The Bertrand Russell International War Crimes Tribunal held its second session at Roskilde, Denmark, from November 20 to December 2, 1967. The author was present.

[6] A fascist law introduced in May 1959 that provided the death penalty or life imprisonment for anyone suspected of even intent to commit “crimes against the state.”

NEXT: Chapter 6 – Taking on the Pentagon