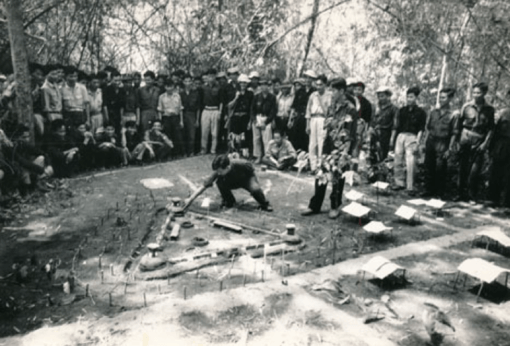

Planning an attack, 1964-65. Photo Wilfred Burchett.

To mark the 50th Anniversary of the 1968 Têt Offensive, CounterPunch is serializing Wilfred Burchett’s Vietnam Will Win(Guardian Books, New York, 1968) over the next few weeks. Readers can judge for themselves the validity of the facts, observations, analysis, conclusions, predictions and so on made by the author. The books is based on several visits to the Liberated Zones controlled by the National Liberation Front (‘Viet Cong’) of South Vietnam in 1963-64, 1964-65 and in 1966-67 and close contacts with the NLF leadership, resistance fighters and ordinary folk. Wilfred Burchett’s engagement with Vietnam began in March 1954, when he met and interviewed President Ho Chi Minh in his jungle headquarters in Thai Nguyen, on the eve of the battle of Dien Bien Phu. He was also on intimate terms with General Vo Nguyen Giap, Prime Minister Pham Van Dong and most of the leadership of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam during the country’s struggle against French colonialism and American imperial aggression. Wilfred Burchett was not writing history as a historian, with the benefit of hindsight, access to archives etc. He was reporting history as it was unfolding, often in dangerous places. He was an on-the-spot reporter, an eyewitness to history. In his reporting, he followed his own convictions, political and moral. The book he wrote after his first two visits to the Liberated Zones, Vietnam: Inside Story of the Guerilla War(International Publishers, New York, 1965) concludes with this short sentence: “The best they [the Americans] can do is to go home.” Vietnam Will Win confirms that.

Unfortunately, it took another seven years (1968-75) of death and devastation – and the extension of the war into Cambodia and Laos – for the U.S. to finally leave Vietnam in ignominy in April 1975. So here, chapter by chapter, Wilfred Burchett exposes the futility of fighting a people united in their struggle for independence, liberty and unity. It also explains, soberly and factually, why they were winning and how they won.

George Burchett, Hanoi

Leadership and Democracy

Deep in the jungle, there was a full-scale model of a corner of a military post surrounded by rows of barbed wire leading to a moat and a section of two-yard-high earthen ramparts studded with watchtowers. Inside the ramparts an inner system of trenches and fire-points zigzagged back toward bamboo and thatch barracks, arms depots, radio center and a headquarters building dominating the others. I had seen the whole complex set out in a sandpit model a few days earlier and listened to explanations of the nature of the buildings and the disposition of the defenses. What I was looking at now was an exact replica of a fortress in nearby Binh Duong province marked down for attack.

I stood with the commander and the political officer of the regiment assigned to the job. We were a few yards away from a key blockhouse which dominated this part of the ramparts. The surrounding jungle was completely quiet except for the chatter of flocks of parrots and the flute-like chirruping of a couple of gibbons. Apart from my companions, there was not a soul to be seen. At the sound of a whistle three men bent double with the weight of heavy charges dashed forward, fixing “satchel charges” against the first row of plaited creepers which represented the “barbed wire.” Within the twinkling of an eye they laid their charges and tiny red flags and faded away. A shot from the direction of a watchtower warned they had been spotted. A volley of machine-gun fire-both shot and volley simulated by banging on empty condensed-milk cans-replied, and another trio dashed forward to repeat the “satchel charge” operation at any second, then the third row, each time planting the little red flags to mark the “gaps” while machine-gunners propelled by their elbows moved up close to the “gaps” that would have been torn in the barbed wire by the “satchel charges.” Assault troops followed, hugging the ground and almost invisible as they snaked forward in the dim light filtering through the heavy jungle canopy.

“Machine guns” were rat-tatting away in all directions as the last trio dashed through the “gaps” and placed a massive pack charge against the base of the blockhouse, hurling in a couple of grenades and dashing back before the “explosion.” A real bugle sounded and the first wave of assault troops rushed through the breach, the leading trio carrying an ingenious combination bridge-ladder bamboo scaling device, a key weapon in the main assault. As the bridge section was hurled across to straddle the moat, the ladder hinged to it automatically swung up to come to rest against the blockhouse wall, the first assault troops clambering over it the moment it hit the wall.

The rapidity with which the bridge-ladder was hurled against the walls and the first shock wave was over the top, hurling dummy hand grenades, had to be seen to be believed. Within seconds the first and succeeding waves were fanning out along the inner trenches and heavy machine guns had been set up on the ruins of the blockhouse aimed at the watchtowers, while 57-mm bazookas were trained on the inner defense installations. The assault developed at lightning speed, troops spreading out in a dozen directions but converging around the main defense positions. Whistles, bugle calls, shouts indicated that a position had been taken, reinforcements were needed or there was a wounded man.

Regimental commander Truong – I never learned his full name – stood straight as a ramrod checking the various phases with a stopwatch, like an Olympic trainer. When the NLF flag fluttered atop the headquarters building, he looked at his watch and said, “Eight-and-a-half minutes. Not bad for the first time. We usually like to complete such operations in 15 minutes and with average opposition, that is about what this one will take, unless there are surprises. Within minutes of the flag’s appearance, a group had formed around one perspiring, stocky young man who I had noticed as particularly active in urging the assault teams forward. By the time we got there an animated discussion seemed to me to be getting quite heated. I asked what was going on.

“The commander of the assault company is being severely criticized by some of the men,” he replied, “because in earlier briefings and in the sandpit model, one machine-gun position had been overlooked according to the defense dispositions here and the layout of the trenches did not correspond exactly. The team that was supposed to seize the radio room as first priority did not make it in time because of this. Such errors can be costly. Our attacks depend on split-second timing, taking the defenders by surprise and completing the operation seconds before the enemy has time to react.”

All around the “compound” there were smaller groups engaged in similar intense discussions. At one group the medium-weapons support platoon was being criticized because one of their machine guns had not been moved forward at the same rhythm as the shock troops despite urgent whistles from the latter when the unsuspected “enemy” machine gun was discovered.

“We will have a summing up discussion afterward,” Truong said. “But sometimes unbeknown to the lower echelon commanders we include small errors like the enemy machine gun and the trench layout mistakes in order to check the vigilance of the troops, to encourage their critical faculties and also their capacity and initiative in adapting themselves to unexpected situations. We don’t want an army of automatons, but teams of intelligent, adaptable human beings. We develop fighters of high morale and of great courage, but courage should be used intelligently. ‘Courage with intelligence’ – that is one of our slogans. Our troops should be ready to lay down their lives at any moment if absolutely necessary, but they are absolutely not to sacrifice their lives uselessly. ‘Determined to fight, determined to win,’ is one of our main slogans, but fight to win and live to fight and win again and again is also an essential concept in our ideological training. For a higher cadre to endanger the lives of the men under his command through carelessness is unpardonable and that is why we encourage the strongest criticism during the preparatory phases of an operation, from the men who have to face the enemy bullets. Apart from anything else, this is also a good way of training future cadres drawn from the ranks.”

Later I watched a heavy-weapons support company assigned to the assault battalion – the regiment’s remaining two battalions were to be deployed to ambush enemy reinforcements – go through training exercises. There was the same extreme realism, the same insistence on perfection of movement and split-second timing, ability to change positions under enemy fire, to respond to urgent signals from the assault forces, speed in assembling and dismantling mortars and heavy machine guns on their base plates and tripods and in changing positions by the anti-aircraft gunners, as model planes strung high up in the trees and manipulated by jungle creepers circled and dived.

A couple of days previously I had been with the same men, grouped around a sand pit model of the whole triangular system of forts that was to be attacked. Among the obstacles were three tiers of barbed-wire fences, a yard-and-a-half-deep moat and two-yard-high earthen ramparts. I took part for only a few hours in a discussion that would last several days. We were interrupted briefly by planes that bombed the area, the first of the bombs landing a hundred yards or so from the sandpit, but the U.S.-Saigon command was obviously not aware of what was going on as the planes never returned.

The main problem being discussed while I was there was whether the attack should be concentrated on one blockhouse with diversionary attacks on others, or whether there should be concentrated attacks on several simultaneously.

Specialists on demolitions and on cutting gaps in the rows of barbed wire and the chief of the heavy-weapons platoon were listened to with great attention when they outlined the problems from their viewpoint. A scout who had conducted reconnaissance missions was questioned several times on details of the fortifications, including the exact depth and width of the moat, the height of the ear them ramparts.

“The bridge-ladders for crossing the moat and scaling the walls are built specifically for each operation,” explained Truong. “They are based on absolutely precise reconnaissance: the bridge section must be of the exact width and the ladder section the exact height required, otherwise the scaling operation, a key part of the assault, can turn into a disaster. They also have to be light enough to be carried by two men, but strong enough to support a man on every rung. After the operation we take them apart and use them as stretchers.”

During the discussions over the sandpit and later after the mock assault, it was impressive to see the complete equality between commanders and men, the freedom with which the rank and file criticized their superiors, and the natural way in which the latter accepted this criticism, patiently replying point by point until everyone was satisfied.

Thuong Chien, the regiment’s political officer, explained that in discussions before an operation, commanders and men were on an absolutely equal footing; that as long as any rank-and-file soldier raised any objection to an operational plan, discussion must continue until he was satisfied. During the operation discipline was total, the rank and file were expected to carry out allotted tasks and execute every command of their superiors without fail. But after the action was over, commanders and men were back on the same equal basis, in the critical summing-up sessions which followed each operation.

“In that way we combine democracy with leadership,” Thuong Chien said, and he went on to outline some basic precepts of the Liberation Army. “Commanders and rank and file are of the same social and class origin, mainly peasants. We are united by hatred of the oppressors and foreign aggressors. We live, study and fight together. Morale is high primarily because of the complete democracy within our armed forces. You have seen part of a typical nonoperational discussion. Often it is only after long, complex discussions that unify of views is achieved. In this way the rank and file know that nothing is being imposed from above, that every suggestion to avoid losses while keeping the main aim in view is welcomed. The command has the benefit of the ideas of the whole collective. Such discussions are a concrete expression of courage and intelligence. For every action that we plan, similar discussions take place at which every phase of the projected operation is analyzed – the preparation, the actual attack, the results. From such critical summing-up meetings we draw conclusions for the next action. Everyone takes part and this produces the best resulting line with an old Vietnamese saying, ‘Three idiots make one wise man.'”

For several weeks on each of two different occasions, I lived and traveled with regular Liberation Army units, spending part of the time at regimental, battalion and company headquarters, and in one regiment I spent several days living and traveling with a ten-man squad. The unity and harmony within the various units, the relations between commanders and men were something wonderful to behold. I have shared a soldier’s life with armies in many parts of the world, starting in 1941 with the Kuomintang troops during the Sino-Japanese war, and with the troops of many other armies since, in over a quarter of a century of reporting wars. But I have never experienced the quality of relations that exist within the ranks of the NLF forces in South Vietnam. To say that they are those that exist between members of an ideally happy family may seem banal, but it is difficult to think of a better comparison, especially in illustrating the solicitude that commanders at every level display towards men under their command and the affectionate relations between the rank and file themselves and between them and their commanders. The fact that commanders and men dress alike, eat the same food, sleep in the same sort of hammocks, share the same bamboo huts in base areas and are in general indistinguishable was impressive enough; even more striking was the complete equality of men and officers in every circumstance. In the very lively discussions which often took place, it was impossible to decide who was the commander and who the commanded.

Did such familiarity and equal status result in any loss of respect or lack of confidence in the leadership at various levels? I was assured it did not. On the contrary, a commander was there just because he had the confidence of his men, was elected by them, and had proved himself. The moment he lost the confidence of his men, he could be removed by majority decision of those he commanded.

A day or two after having joined the ten-man squad, after our evening meal of rice and salted fish, most of the squad members joined others from the platoon to which the squad was attached, and set off, myself and my interpreter following them down a narrow jungle trail to a little clearing, where everyone squatted down on his heels with a tiny bottle lamp in front of him. Although it was a clear night, one had to strain his eyes to spot even a single star glinting through the thick leafy canopy. The participants were platoon members of the Liberation Youth Association. Each pulled out a small notebook, and one, who my interpreter whispered was the ‘chin tri vien’ (political representative), spoke for a few minutes in a low voice. In the same subdued tones, others followed in what was obviously a very serious discussion. Although this was a base camp, there was an enemy post less than two miles away. I asked why they did not meet in the bamboo barracks. “Other comrades need to rest; we are meeting in a rest period when noise is not permitted,” the interpreter whispered back.

The theme of the discussion was the difficulty in getting to real grips with the enemy. It was around the beginning of 1965 when the Saigon forces were in full disintegration following the Binh Gia defeat. “The enemy is no longer falling for our tactics of attacking enemy posts and wiping out enemy reinforcements,” the interpreter said, summarizing the gist of the discussion. “In recent weeks they tend to cut their losses and when we attack a post, the enemy command prefers to lose it and abandon territory rather than lose more effectives by sending reinforcements to fall into our ambushes. But to win the war we have to wipe out the enemy forces. They have even withdrawn from a number of smaller posts that we intended to attack, abandoning lots of territory and concentrating in bigger posts with a battalion or more in each. The enemy’s divisional commanders are trying to preserve their troops in this way. This is a new situation for our forces and the ‘chinh tri vien’ says we will have to adopt new tactics. We shall have to go after the enemy in his garrisons; we can no longer count on him coming to us, his morale is too low. We must be prepared to go right into their posts, even big complexes of posts, and destroy them. To do this we must improve our technique, face up to new problems. We must perfect the speediest and most efficient way of laying mines, achieve greater precision in coordinated assaults and acquire the technique of rapid and complete destruction of the enemy’s artillery positions inside the posts We must be prepared to move more swiftly than ever, especially after the attack, because these big posts are further away from our jungle bases than those we have been attacking till now. Our troops should be able to travel lighter after an attack because from now on we need no longer pay attention to carrying off enemy arms but to wiping out his effectives and his artillery and base installations.”

The rest of the discussion was of a technical nature, everyone taking part by raising his notebook when he wanted to speak. From then on the only difference between men and commander was that the ‘chinh tri vien’ decided who spoke in case two raised their notebooks at the same time. The platoon’s military commander took his turn with the others and apart from the fact that he seemed to be listened to with a little more deference, he could not have been spotted. Suggestions were made to lighten equipment by having the kitchen staff prepare meals in advance at the closest possible point consistent with safety to the takeoff place for the attack, so that the troops would not have to carry rations. The food could even be left in a cache with a guard. A demolitions expert pointed out that as heavier charges would be necessary to blow up such bases, the comrades in the regimental arsenal should try to produce more powerful explosives without increasing the weight. Someone suggested that as the enemy’s morale was obviously low, those in charge of propaganda should redouble their efforts to reach the puppet troops in their new bases to warn them they would not be safe there and had better think of deserting. Several disagreed with this and said that it was better not to warn the enemy of what was in store for him but first make sure of dealing a very heavy blow, wiping out one of the big bases and then using the result to carry out propaganda in the others. It was agreed to ask the company commander to arrange more frequent meetings at company level as soon as the lust of the new type of targets was selected. This was the only decision taken. The meeting lasted just one hour, then all of them pocketed their books, picked up their lamps and went back to the barracks.

“Discussion on this will continue now every night among the entire squad, not just those who are Liberation Youth Association members,” explained my interpreter. “The war is really entering a new phase and everyone will be expected to make his contribution to how the new problems should be tackled. The political representative will make a report on this meeting to the ‘chinh tri vien’ at company level, and he will make a synthesis report of the discussant of the three platoons directly to the regimental command. A similar synthesis report at regimental level will go directly to our high command.”

Back at the regimental command, relating my impressions of the excellent relations between commanders and men and the very high morale of the troops at every echelon down to the squad, the political officer, Thuong Chien, said that in the viewpoint of the high command, the “three major factors in still further improving the fighting spirit of the Liberation Army are to give correct leadership and correct political education; to pay great attention to improving tactics and technique; and to pay great attention to constantly raising the material and cultural living standards of the troops, ensuring a steady improvement in everything from food and sports to poetry and music.”

As for the high morale, he added, “This is because of correct leadership at the top which directs political education based on a clear distinction between enemy and friends. This is the greatest source of our troops’ combativity. A logical consequence of this is that we are based on the people. We fight for the cause of the people and we are supported on every hand by the people. This support has been a great factor in our rapid development and a great source of satisfaction to our fighting men.

“Commanders and men have all risen from the ranks of the people. None of us have been formed in academies or institutes. The question of superior morale is one of political and ideological attitude. That is why we never cease stressing the importance of political leadership and education and genuine democracy within our armed forces. Only when a fighter has correct politics and ideology can he freely accept the absolute iron discipline which we demand on the battlefield; only when a commander has correct politics and ideology can he behave like a real leader of men on the battlefield and freely accept the democratic spirit we demand off the battlefield.”

This combination of leadership and democracy obviously has nothing in common with the sort of example cited by Régis Debray in Revolution in the Revolution, in which combatants during the Spanish Civil War “argued about their officer’s orders in the heat of battle, refusing to attack such and such a position, or to withdraw at a given moment, holding meetings under enemy fire to decide what tactic to follow…”[1] Leadership on the battlefield in South Vietnam means that the commander directs the implementation of decisions arrived at by the most democratic process possible, every detail of which has been agreed on beforehand by those taking part in the attack. If the decisions are wrong it is a collective responsibility. If the implementation fails due to bad leadership, the leader will be changed.

One thing noted during actions in which I involuntarily took part, due to surprise encounters with U.S.-Saigon troops, as well as in training exercises and barracks life, was the absence of the sergeant’s bark. In action everyone seemed to know what he had to do, even in a surprise situation, and commands were like urgent exchanges of a few words at a noise level just sufficient for the communications to be understood. Whistles are used for obviously coded signals and bugles for assault. One rarely hears a shouted command, doubtless partly because of long years of living “integrated with the enemy,” as one commander expressed it, but also because discipline and confidence in the leaders is such that a commander does not have to shout in order to impress. The quietness with which everything is handled among the NLF units is a characteristic that has impressed all who have visited them. It is something very special, and inseparable from the harmonious relations between commanders and men, which in turn is a consequence of the constant stress on ideological attitudes.

Virtually every regimental, battalion and company commander of the Liberation Army with whom I talked had started as a rank-and-file soldier in the self defense guerrillas, proving himself first of all as a guerrilla leader and then graduating through the regional troops to the regular army. By the time he took over a platoon or a company of the Liberation Army, he was a veteran resourceful commander of a quality, even from a purely military viewpoint, infinitely superior to his opposite number in the Saigon forces or in the U.S. Army when it arrived.

There are three types of armed forces. Local self-defense guerrillas whose main job is to defend their own villages, pin down local enemy forces in nearby posts, keep those posts permanently encircled, carry out propaganda and “persuasion” work among the enemy. In early 1965, as the Saigon forces were withdrawn from encircled posts all over the country, and the military tasks of the self-defense guerrillas became much lighter, the young women started taking over, releasing men for service in the regional troops and the regular army. In the early days of the insurrection, women served also in the latter two bodies, but from 1965 onward they were encouraged to go back and form the backbone of the self-defense guerrillas and production teams. The self-defense guerrillas are part-time soldiers, serving in rotation in tasks which demand permanent posting of troops, such as encirclement of enemy posts, but otherwise taking part in production. They are armed mainly with rifles, but by 1965 there was a sprinkling of automatic weapons in every village and plenty of hand grenades and mines. Most villages have their own small arsenals for at least making mines. The local guerrillas are responsible also for maintaining and constantly extending the “passive” explosive “booby traps” to “platoons” of bee-handlers releasing swarms of vicious outsize bees to attack hostile intruders.

Regional troops are full-time soldiers, much better armed than the self-defense guerrillas and functioning in a defined geographical area, usually a district or group of districts. Their job is to deal with enemy forces stationed in the same area, break up enemy raids, lay ambushes, encircle bases, attack posts within the region. The regular Liberation Army deals with the enemy’s mobile reserves, initiates offensive operations and attacks major enemy concentrations. When the enemy employs mobile forces in a sweep operation into NLF-controlled territory, then all three branches of the NLF forces coordinate their activities. Each branch has its standard assigned role, valid for whole phases of the war, and it changes only when the situation changes.

In step with the development of the “mind behind the gun,” there was also a steady evolution of military tactics, each phase of which a commander had to master before he could become even a platoon leader. After the transition from passive to active defense, there were diversionary actions in one area to prevent the enemy from concentrating on one particular village or district. After strategic hamlets were set up under the guns of military posts in their immediate vicinity, there were night attacks against these posts. For the NLF forces this represented a big step forward. And as the regular forces developed, there was a combination of night attacks by regional troops and self-defense guerrillas on enemy posts with major battles waged the following day by the regular army, usually fighting from fixed positions, as they ambushed enemy reinforcements with the “attack enemy posts – wipe out enemy reinforcements” tactics. At the battle of Binh Gia, the Liberation Army went over to war of movement and had clear-cut victories in several classical daytime battles. By that time (the first weeks of 1965), the Liberation Army was making skillful use of feint attacks and diversionary actions, maneuvering enemy battalions into positions that enabled them to launch the decisive attacks, usually with such a sudden and devastating concentration of fire that the outcome was decided in the first few minutes of-the action.

Every new phase required new qualities of leadership, new demands on grasp, initiative, ingenuity and intelligence. If a commander could not keep up with the new tasks, he dropped back into the ranks with no hard feelings, and another came forward.

This was possible because of the complete unity of aims of the whole collective. Promotion does not come easily. Soldiers advance in as tough a military school as the world has ever known, and perhaps the toughest. South Vietnam’s peasant guerrillas, who have been fighting off and on four more than a quarter of a century, provide the Liberation Army with inexhaustible, rich resources of unequalled leadership cadres.

Within the Liberation Army, general education goes hand in hand with military and political training, and this facilitates the grasping of modern techniques. No book-learning alone, no military academy, could provide the qualities of leadership that experience and political and military training have given commanders in the NLF forces. And no armed forces, except those fighting on for such just aims, could dare to introduce the same system of democratic leadership as the guideline for its armed forces.

Notes.

[1] Translation from Régis Debray, Révolution dans la Révolution, Paris, François Maspero, 1967, p. 124.

George Burchett comment: I was present when Régis Debray and my father first met in our flat in Paris. My father apologized for criticizing him in his book while he was in prison in Bolivia and unable to respond. They became excellent friends.

NEXT: Chapter 5 – Winning Hearts and Minds