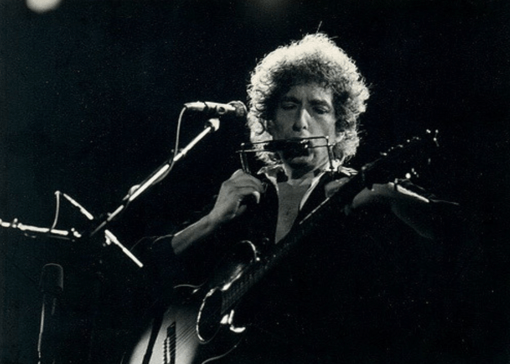

Photo by Xavier Badosa | CC BY 2.0

“He who controls the past controls the future,” wrote George Orwell in 1984. Daniel Wolff doesn’t want to control the past, but he does want to paint an accurate picture of it. He does it well in his new book, Grown-Up Anger: The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913 (HarperCollins).

Wolff’s story revolves around the Kewanee Peninsula–the northernmost part of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula–which once had some of the richest copper deposits on earth. Seven thousand years ago, Native Americans were able to mine it well enough to make tools. The advent of modern technology made the mines more productive, but the work was far from easy.

The early twentieth-century work day at the Calumet & Hecla mines on the Kewanee Peninsula “began by riding a thousand feet down into ill-lit, poorly ventilated mining shafts. There, the workers spent ten hours manning ‘widow makers,’ 170-pound drills that they held overhead, gouging out rock in search of copper…While the company’s stockholders received 400 percent returns on their investment and the general manager of the mine got a yearly salary of $125,000, workers were paid under a dollar a day.”

As Christmas approached in 1913, the workers had been on strike at C&H in Calumet, Michigan for almost five months. The ladies auxiliary of the union organized a Christmas party at Italian Hall for the miners’ kids. They sang songs and opened presents. According to famed labor organizer Mother Bloor, who was present, just as a young girl sat down to play the piano, “a man pushed open the door and shouted: ‘Fire!'”

The crowd rushed downstairs for the building’s one exit. Adults and children fell and piled up on top of each other until, after only a few minutes, seventy-four of them were dead, sixty-three of them children. “I saw the marks of children’s nails in the plaster,” Bloor said, “where they had desperately scratched to get free, as they suffocated.”

“If someone deliberately shouted “Fire!” and set off the panic–and all the inquiries seem to agree that’s what happened–that person was liable for the death of sixty-three children and eleven adults. The majority of witnesses testified that the man who shouted was wearing a [pro-management] Citizens Alliance pin.”

Management worked for the real owners of the Calumet mines–New England movers and shakers who operated under the innocuous moniker of Boston Associates. The roots of the wealth of many of them traced directly back to slavery. The Associates opposed the Civil War and were “known as Cotton Whigs, their textile mills depended on what one commentator called an alliance ‘between the lords of the lash and the lords of the loom.'”

They may have been the lords of both. Between 1880 and 1910, there were a little over 1,000 deaths just in the copper mines of the Michigan Upper Peninsula. This compares to 3,705 lynching deaths nationwide in the same period. As Daniel Wolff writes: “It was like a war–an unseen, below-ground war.”

That stairwell of crushed humanity at Italian Hall eventually became a song, roughly following the evolution described by James Baldwin in Just Above My Head: “Music can get to be a song but it starts  with a cry. That’s all. It might be the cry of a newborn baby, or the sound of a hog being slaughtered, or a man when they put a knife to his balls.”

with a cry. That’s all. It might be the cry of a newborn baby, or the sound of a hog being slaughtered, or a man when they put a knife to his balls.”

Or the cry of children gasping for breath as they tried to escape a people’s palace turned coffin. Woody Guthrie eventually heard the story from Mother Bloor. He wrote a song about it, “1913 Massacre,” and recorded it in 1945.

Bob Dylan discovered “1913 Massacre” sometime around 1960. He may have found it on a Woody Guthrie 78, a Rambling Jack Elliot British LP, or just heard it in the Minneapolis coffeehouses where he performed. Once Dylan left the Twin Cities for New York he played the song publicly just once more, at a Carnegie Hall concert in 1961. He never recorded it but his first album did contain an homage to Woody Guthrie, “Song to Woody.” The melody was taken from “1913 Massacre.”

At age thirteen, Daniel Wolff first encountered Bob Dylan on the radio, the electric sound of “Like A Rolling Stone.” That led Wolff back to Dylan’s early acoustic work, neatly reversing Dylan’s sonic path. Somewhere on that journey he found “1913 Massacre” on an album by Woody Guthrie’s son Arlo.

Wolff says that what first attracted him to Bob Dylan was his anger, which finds its echo (and perhaps one of its sources) in Guthrie’s song, which concludes:

The parents they cried and the miners they moaned

See what your greed for money has done

Guthrie and Dylan took sides even though they didn’t come from the same economic background as the miners of the Kewanee Peninsula.

I wasn’t in the path that John Steinbeck called the Okies…My dad, to start with, was worth about thirty-five, forty thousand. He had everything hunky-dory.–Woody Guthrie

Charlie Guthrie, Woody’s father, owned thirty farms with hired help and two residences in the new state of Oklahoma, which joined the Union in 1907. Charlie Guthrie became wealthy in part because he hustled Indians out of their land.

Bob Dylan’s father was a partner in an electrical appliance store in Hibbing, Minnesota. Bob’s first girlfriend said about him: “He was from the right side of the tracks, and I was from the wrong side.”

But Guthrie and Dylan both came from places largely defined, just like the Kewanee Peninsula, by what was in the ground. Guthrie’s youth in Oklahoma paralleled that state’s oil boom while Dylan’s Hibbing was smack dab in the middle of the Mesabi Iron Range. There was local work to be had for young men but those two had other plans. Guthrie left early on for Los Angeles, Dylan for Greenwich Village.

Guthrie and Dylan both grew up where there was a past and a present of intense unrest–small farmers in Oklahoma, miners in Hibbing. In 1916 there was a mass walkout from the Mesabi Range iron mines and it wasn’t long before Hibbing “was being patrolled by sharpshooters in armored cars.”

Unrest led to protest. Oklahoma had one of the country’s highest percentage of socialist voters. In 1912, the year Woody Guthrie was born, Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs got 897,000 votes nationwide, six percent of the total cast.

Dylan’s Hibbing was the birthplace of the Finnish Socialist Federation, which had 225 locals and 11,000 members, including quite a few among the miners of Upper Michigan. Bob Dylan described northern Minnesota as “an extremely volatile, politically active area — with the Farmer Labor Party, Social Democrats, socialists, communists.”

All this history, fueled by anger, is reflected directly and indirectly in the music of Guthrie and Dylan. But the music’s roots go even deeper.

In 1907, the new state of Oklahoma “was duplicating the Old South’s system of sharecropping.” It was based on stolen land and its southeastern quadrant was known, tellingly, as “Little Dixie.” The elections that year in Oklahoma featured a populist combination of racism and an attack on big business, a framework that still plagues us (see Trump, Donald). In 1907, it led to a Democratic sweep of every statewide office and also brought the likes of Charlie Guthrie, running for District Court clerk, to power.

By 1937 Woody Guthrie was co-host of a radio show in Los Angeles. Evidently influenced by his Oklahoma upbringing, one day he sang a song on the air called “Run, Nigger, Run.” Guthrie received a letter of protest from a black listener and he quickly made an apology.

The apology appears to have been sincere. Living in New York City three years later, Guthrie wrote a song called “Hangknot, Slipknot,” dedicating it to “the many Negro mothers, fathers, and sons alike, that was lynched and hanged under the bridge…seven miles south of Okemah, Oklahoma, and to the day when such will be no more.” Okemah was Woody’s hometown.

“Hangknot, Slipknot” is one of Guthrie’s best if not best-known songs. It’s a coiled snake of restrained anger that begins by describing the technique for making a hangman’s noose, declares the slave to be his brother, and ends by describing the entire legislative/judicial system as a slipknot.

Bob Dylan went further a generation later with “Only A Pawn In Their Game,” a song he wrote in quick response to the assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Mississippi in June 1963.

It’s a protest against the shooting, but it also questions the standard protest song, cutting through the black and white conventions of Greenwich Village and the folk world to emerge not far from the old Popular Front idea that racism is a product of the larger economic system.

Dylan sang the song at a rally in Greenwood, Mississippi, where violence against the civil rights movement was at a peak. He sang it again for 300,000 people at the March on Washington. The importance of “Only A Pawn In Their Game” can still be seen in the way that poor whites today are almost universally regarded as hopelessly ignorant if not downright fascist, not to mention being blamed for the election of Donald Trump. Dylan’s song insists that we see “The poor white remains/On the caboose of the train.” If we embrace that truth, we may see ways we can all escape being mere pieces on their chessboard.

There have been many attempts in our history to do just that.

“There was that moment [during the strike in Calumet] when the workers were chanting, ‘We are the bosses,’ but by the Christmas party, that was long gone,” Wolff writes. “And the Western Federation of Miners never thought of the strike in those terms. It wasn’t trying to change the basic system; it had conceded that the earth–what was dug from the earth–was already bought and owned. It just wanted the workers to get more of a share, to be partners in the business.”

That strategy worked for a section of the working class as long as they had a social contract with the employers–economic survival in exchange for support for the bosses’ strategic initiatives (when I was a steelworker, the company gave us paid time off to watch a film, Where’s Joe?, that was made by the union and preached the message that our real enemy was foreign steel). In any event, real wages went up from the end of World War II until the mid-1970s.

This may have been what Woody Guthrie meant to prophesy when he said “The only New Deal that will ever amount to a damn thing will come from trade unions.” But today real wages have been dropping for forty years and union membership in the private sector today is less than 7 percent of the workforce. Michigan, a traditional bellwether of blue collar strength, passed a right-to-work law in 2012, the 24th state to do so.

The social contract that kept millions of families afloat has been unilaterally torn up and discarded. For instance, there is now a large group of port truckers in Los Angeles who, according to a USA Today investigative report, work under conditions of indentured servitude, taking home as little as 67 cents a week. Meanwhile, the righteous Fight For Fifteen campaign of fast food workers is in a race against time as the automation of McJobs draws closer every day.

With a new social contract impossible in a world going rapidly in a laborless direction, we are again confronted with the challenge and the opportunity to “change the basic system.” We are taught to look at previous efforts to do that, such as the strong socialist voting upsurge in Woody Guthrie’s youth, as failures. It would be more instructive to see them not as ancient aberrations, but as steps on a winding road that is wending its way back to us.

Consider that recent polls show up to 40 percent of all Americans prefer socialism to capitalism and that a majority of millennials feel that way. Peter Sokolowsk of Merriam-Webster points out that “Socialism has been near the top of our online dictionary lookup list for several years.” In 2015, socialism took the top spot on that list, with a 169 percent increase over 2014.

This may just be kneejerk frustration but it may run deeper. According to a 2016 report from Business Insider: “Mainstream media painted Trump’s election victory as a ‘white working class revolt’. The real story is that voters who fled the Democrats in the Rust Belt were twice as likely either to vote for a third party, or to stay at home, rather than to embrace Trump. Compared with 2012, three times as many voters in the Rust Belt who made under $100,000 a year voted for third parties. Similarly, compared with 2012, some 500,000 more voters chose to sit out this presidential election. If there was a Rust Belt revolt this year, it was the voters’ flight from both parties. The story of a ‘white working-class revolt’ in the Rust Belt just doesn’t hold up. In the Rust Belt, Democrats lost 1.35 million voters. Trump picked up less than half, at 590,000. The rest stayed home or voted for someone other than the major party candidates.”

What if this pox-on-both-your-houses Rust Belt revolt coalesced under a banner inscribed with Woody Guthrie’s vision of a society where people would “own everything in common. Common means all of us.” The national despair which marks the Trump presidency could turn into hope.

The need for a movement based on solutions and not just protest is becoming a matter of life and death. Daniel Wolff might be describing Flint or the war in Afghanistan when he writes:

Guthrie’s song is the story of how the American system kills its own. It describes a deliberate act: dozens of children are smothered to death because a small group of people own the wealth of the earth–and they’d rather kill than share.

As for the music, will another Woody Guthrie or Bob Dylan emerge from the social turmoil of our times? I posed that question to Daniel Wolff. He replied: “A next Dylan? Nope. Same way he wasn’t the next Guthrie. Or Guthrie the next Joe Hill. Times and needs and music change.”

So will it be some sixteen-year-old rapper? Some middle-aged troubadour cast adrift from middle class moorings and putting his or her anger into song? Are there ten thousand people under the radar already fulfilling that role?

Who knows? But we do know that to navigate the future, we need to understand the past. Daniel Wolff has illuminated an important chunk of it to guide us on our journey.