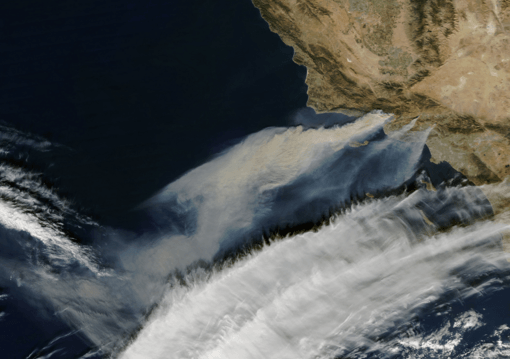

Photo by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center | CC BY 2.0

Southern California’s Thomas Fire, the state’s fourth largest, continues to grow. To date, it has consumed over 250,000 acres but in the middle of its burn area, which stretches from Santa Paula in the south east to Santa Barbara in the north west, the Ojai Valley (barring an extraordinary turn-of events), has survived. A week ago, the local weekly, The Ojai Valley News, emblazoned its front page with the banner headline, “Ring of Fire”, a phrase that had been in local circulation for several days previously as residents watched the flames encircle their communities on their seemingly inevitable way to the coast.

Many of us who have reached a certain age cannot hear that phrase without hearing, in our mind’s ear, the thudding voice of Johnny Cash running through his sister-in-law’s honky-tonk ditty of 1963. His earnest rendition has become a cultural touchstone: now, in central coast California and its inland valleys, it has become entwined with the epic events of December 2017 when much of the landscape that lies to the south of the Santa Ynez transverse mountain range was charred in the ring of fire that girdled the Ojai Valley; as it continues to burn to the north and west, it has already destroyed over a thousand structures – the surrounding chaparral blackened, somber, and pungent with congealed super-heated resins.

Cash had a great deal of history in the area. He recorded the song Ring of Fire in a small Ojai recording studio while living in Casitas Springs, the western-most community in the Valley. The town now proclaims itself as “The Home of Johnny Cash” and the trailer park he purchased for relatives to manage still stands forlorn in an area whose center is anchored by a convenience store, nameless but for the red neon sign over its door that reads ‘Bait and Liquor’.

Casitas Springs was founded in 1834 when local Chumash Indians, formerly wards of the Mission San Buenaventura were relocated to pastures along the Ventura River flood plain half a dozen miles inland from the coast. There they settled, built rough shelters (euphemistically called casitas and memorialized in the town’s name) and led lives tragically foreclosed by both the loss of their connection to a tribal life and the enforced institutionalization to which they had succumbed during the Mission era. Their sad histories were washed away in the frequent floods that plague these rank bottom-lands; their archeological footprint, primarily evidenced by their basketry, destroyed by the brush fires that periodically sweep along the escarpment to the south. The fire this time skirted Casitas Springs and the three other towns that run east between the Santa Ynez mountains to the north and Sulphur Mountain to the south – the Valley saved by its topographical character, its heavily irrigated buffers of citrus and avocado groves, accommodating winds and the battalions of fire fighters who worked at its margins.

For all its local resonance, this literal ring of fire also reflects the wild fires that customarily girdle the planet and are shown in a stunning animation on NASA’s Eco Earth website generated from information transmitted by its Terra satellite. Perhaps most of these fires represent versions of slash and burn agriculture, but whatever their origin they are now all non-human creatures of the Anthropocene, their fiery conflagrations, exacerbated by global warming to some unknown degree, reflections of the burning of the planet’s stored solar energy scavenged from its crust.

The Thomas fire has now swept through territory once lightly populated with Chumash Indians who regularly burned their food-gathering lands. As Kat Anderson has shown in Tending the Wild, Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources, 2006, local Indians managed their wild food resources by burning the land to encourage their growth and to create clearings in which they could better hunt game. While the coastal Chumash relied heavily on sea food, inland groups harvested acorns as their staple supplemented with chia seeds, the fruits of the holly leafed cherry and small game. The untouched wilderness eulogized by John Muir was in fact a carefully managed environment, with swathes of chaparral charred in controlled burns where the plants had long co-evolved with regenerative lightning-sparked conflagrations.

Following the European invasion of California in 1769 and the subsequent sacking of the territory by Anglo Americans in the mid nineteenth century in pursuit of gold, rampant infrastructural development in these fire-lands has raised the stakes for the rapid containment of its cyclical irruptions. Californian and Federal agencies, as well as municipal fire-brigades from all over the western states and the National Guard have massed their land and air forces to battle the Thomas fire. They are backed-up by a large police presence and loosely aggregated community support groups. There is a sense that in controlling the flames, in taming their wildness, the chaparral is being returned to the asylum, its place of subjugation. As Thomas H. Birch notes in The Incarceration of Wildness: Wilderness areas as Prisons, “when this place is made, and wildness is incarcerated in it, the imperium is completed”.

If we accept fire as a natural event (although, in the case of the Thomas fire its two starting points were of an anthropogenic origin), then the determination to contain it is very much in the tradition of Mao’s Great Leap Forward of the 1950’s which proposed conquering nature through human intervention. In an arguably more enlightened twenty-first century America might we begin to move towards policies of accommodation and of co-existence with non-human entities and their often cataclysmic manifestations? Reasonable containment strategies could then be incorporated into urban planning practices, or in the case of existing developments, accorded the same level of priority as other infrastructure upgrades in the areas of transportation, public health, communications and the supply of goods and services.

To continue the manic patchwork of whack-a-mole fire suppression is a profoundly reactionary approach that both validates and preserves the existing incongruities of urban and suburban developments within areas whose ecologies requires them to burn. In many respects, this reaction echoes the mindset that drives the U.S. military towards the lethal suppression of armed resistance in areas of conflict rather than pursuing soft strategies of social, political, and economic accommodation that might remove the underlying grievances of the putative enemy. In both cases, these aggressive policies are the testosterone fueled products of the Neolithic mind.

In addition, the perception of the firefighter as Hero (who saved our town/house/life/pet) gets in the way of a sensible appraisal of the issues at stake. Firefighters do their job and for the most part are handsomely paid for their efforts (prisoners from state penitentiaries on the fire-line excepted) and while they often display extraordinary bravery in the protection of stranger’s lives, their property and pets, our adulation likely confirms in them and their command structure a sense of the ineffable righteousness of their work. We, as a community, are thus locked into the whack-a-mole ethos, which stands in the way of a measured coexistence with forest fires. Co-existence and accommodation do not represent humanity’s defeat in its battle with the elements but indicate a level of solidarity with the non-human and of an appropriate humility in acknowledgement of the other powers with whom we share the Earth.

In the aftermath of the fire running through areas of Upper Ojai there were several instances of looting of evacuated and damaged houses. I witnessed the arrest of a suspected looter on my street. Three Ventura County Sheriff’s black and white SUV’s were pulled up behind a beige Chevy Suburban bulging with boxes of household goods and clothing. Two bicycles were thrown haphazardly on the roof rack. A deputy knelt at the curb carefully probing one box of civilizational detritus at a time. The cuffed suspect was standing by his vehicle, his female companion still in the front passenger seat. I pulled up and my enquiring gaze was met with an explanation from one of the sheriff’s deputies that they were patrolling the streets around the burn area apprehending looters and other ‘undesirables’. I drove off, that last word etched in my consciousness.

Some years after Cash recorded Ring of Fire he went to Folsom prison, actively consorted with the state’s undesirables, then entertained and demonstrated solidarity with them. He revived his fading career by adopting an outlaw image as ‘The Man in Black’. He understood the plight of all those who refused to be totally coopted by the rules-making capitalist imperium. Perhaps, as a profoundly Christian man, he foresaw a day, in an epoch we now call the Anthropocene, when the ‘undesirables’ (in the neo-liberal lexicon, but one step away from the non-human), would inherit the Earth.