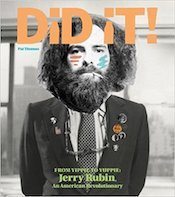

Pat Thomas, the author of “Did iT! From Yippie to Yuppie: Jerry Rubin, an American Revolutionary,” had noticed that there were six books about co-activist Abbie Hoffman, but none about Jerry Rubin, so Thomas welcomed the challenge. Seventy-five co-conspirators were interviewed for revealing anecdotes galore (including me), and this tome is a unique oral and visual history heavy enough to sink into your coffee table.

Rubin had written a few books himself, though. The first was 1970’s “DO iT!” Under the influence of Ritalin, he recorded all the material swirling in his mind, and his girlfriend Nancy Kurshan transcribed 700 pages that had to be severely trimmed down. That book was heiress Patty Hearst’s favorite, radicalizing her, especially the part about rebelling against elite parents.

In January 1964, Rubin was 26 with a thick handlebar mustache, bored as a journalist for the Cincinnati Post. He moved to UC Berkeley for grad school, but dropped out during his first semester. He then asked so many questions about local politics, filling his notebook so much, that several activists thought he was a cop. But by May 1965, at the Berkeley campus he had organized a Vietnam teach-in, the largest in the U.S.

He called me in New York, inviting me to speak there. I urged him to also contact folksinger Phil Ochs, who could perform appropriate songs between speeches. Rubin had never heard of Ochs, but he accepted my suggestion. They would eventually become deep friends.

When Rubin was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee, he wore a rented American Revolutionary costume, and he gave out copies of the Declaration of Independence. As the marshals carried him out, he yelled, “I want to testify!” He had manipulated the media to spread his patriotic message on radio, TV and the front pages of newspapers across the country.

Peace activist Dave Dellinger invited Rubin to be the project director of an anti-war event at the Pentagon in October 1967, where Ed Sanders of the Fugs would lead the ritual of levitating the building. Rubin moved to New York and met Hoffman. Mutual admiration developed quickly. Their brains were complementary. Hoffman was the right lobe (spontaneity) and Rubin the left (list-making).

They led a nonviolent group to Wall Street and threw a load of single dollars from the balcony onto the floor, where stockbrokers stopped everything and grabbed the cash. These political pranksters then explained to the waiting reporters the connections among money, poverty and war.

An idea of Rubin’s sidekick, Stew Albert, glued the straight New Left together with stoned hippies. That hybrid phenomenon was already in process at various protests. It would serve as a conception of the Yippies, the Youth International Party, which was born at the home of Hoffman and his wife, Anita, on the afternoon of Dec. 31, 1967. This informal alliance of activists celebrated with Colombian marijuana at our first meeting to plan a counter-convention to the Democratic National Convention scheduled for Chicago in August 1968. On the way to a New Year’s Eve party, I rubbed some fresh snow into Rubin’s bushy hair. It was a Yippie baptismal rite.

In Chicago, a sense of competition was developing. Hoffman bought a pig for president, but then Rubin decided to purchase a bigger, meaner, uglier pig

that was released at City Hall. Tom Hayden chastised Rubin: “Are you going to have a press conference and make very serious statements, or are you going to have a whole Yippie guerrilla theater performance?” Meanwhile, billy clubs and tear gas were being used indiscriminately and sadistically outside the convention hall. Later, a government-sponsored investigation concluded that it was “a police riot.”

Nevertheless, in 1969, a trial took place of the Chicago 8, including Black Panther Bobby Seale, whose crime was to deliver a speech. His lawyer was sick, but the judge wouldn’t allow him to defend himself. Seale shouted that he had such a right. Who could’ve guessed that in an American courtroom, a defendant’s mouth would be gagged and his body shackled to a chair? When the judge finally kicked him out of the trial, it became the Chicago 7, two of whom were Yippies. As if to prove it, Rubin and Hoffman entered the court one day wearing judicial robes.

In biographer Thomas’ diligent research, he realized that the men got credit for the Yippies while the women weren’t acknowledged. Powerful spouses — Anita Hoffman and Judy Gumbo Albert — deserved recognition. So did several others. Judy Lampe designed the Yippie logo, using a style of Japanese lithography she had studied. Robin Morgan left the Yippies to organize a feminist rally against the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, N.J., in September 1968. The Yippies’ office was run by Kurshan, Rubin’s girlfriend, and Walli Leff, whose husband, Sam, served as the Yippies’ archivist. In 1970, Kurshan left Rubin because of his fame and egotism. Without her, his ability to be a leader temporarily disintegrated.

Likewise, John Lennon had gone through an awful breakup with the Beatles, fueled by disagreements with Paul McCartney. Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, moved to New York and met Rubin, who persuaded them to play at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally in Michigan. Sinclair was the leader of the White Panthers and the rock band the MC5, and the rally got him out of prison, where he’d served two years for a pot bust.

After the protests at the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami, Rubin moved to San Francisco and dropped out of politics. He became a New Age junkie — meditation, the est movement, yoga, Rolfing, health food — happily recommending the virtues of self-awareness therapy. But later on, he confessed, “There’s not really much for me to do, and I’m pretty bored right now. The war is over.” Yes, the Yippie was gradually morphing into the Yuppie.

His love life had a certain pattern. On his first date with Stella Resnick, a therapist, he said: “I’m going to marry you.” She wanted to be independent, so they lived together until he was too controlling. Back in New York, his “I Want” laundry list included “I want a beautiful blond society wife.” Mimi Leonard fit that description enough that before they had left for dinner, he’d asked her to marry him. She wasn’t that interested, but five weeks later they moved in together and married the next year.

They also developed a creative partnership. Their first collaboration was “The Event: 14½ Hours That Could Change Your Life,” but they both also needed to get jobs. She became a commodities broker at ContiCommodity, a top firm. He appreciated her success and decided to go to Wall Street. He finally was titled marketing director at the John Muir Co. Many people thought Rubin had sold out, not knowing that his job was “investigating new companies of the future, including those producing solar and other alternative-energy sources.” He created a weekly networking salon, a precursor to Facebook and LinkedIn.

In high school, Rubin wore a bow tie. Nobody else did. But in countercultural days, he claimed that a necktie was a hangman’s noose. However, now that he was dancing in the world of finance, he wore a necktie, sort of like having worn the appropriate revolutionary costume for HUAC. He stated, “Money is the long hair of the ’80s.”

He actually sent out a press release requesting that the media no longer refer to him as a former Yippie leader. I couldn’t resist publishing in the Realist magazine this headline: “Former Yippie Leader Asks Not to Be Called Former Yippie Leader.” Indeed, Rubin and Hoffman went on tour with a debate, “The Yippies Versus the Yuppies.” At a San Francisco nightclub, I moderated their performance and mentioned, “If Abbie Hoffman were to throw money in the Stock Exchange today, this time, Jerry Rubin would invest it.”

In “Did iT!,” the biographer captures Rubin’s story with fairness — affirmative and negative perceptions are both presented through the subjectivity of 75 prisms. Dellinger regretted inviting Rubin to organize the Pentagon event. Mimi and Jerry had two children, and she divorced him, yet they remained best friends and partners.

Hoffman and Ochs both committed suicide, and Rubin might as well have: On a November evening in 1994, he was jaywalking across Wilshire Boulevard when he got hit by a car as he turned around to wave at his girlfriend, Tiffany Stettner, and a friend, Fred Branfman. They’d just had a meeting to discuss his organization about helping disenfranchised black children in Los Angeles, providing all kinds of creative ways for them to be educated. He died two weeks later.

When Rubin was alive and anyone criticized him, Hoffman defended him: “You can say that you lay across the train tracks leading to the Oakland Depot where the soldiers were being sent overseas to die in Vietnam.” Hoffman wasn’t aware that Jack Kurzweil, Berkeley professor and activist, said to Rubin, “One of the young kids who was so bound up in the passion and ecstasy of it that he was going to lie down on the tracks. Jesus, we’ve got to drag the kid off the tracks.” Rubin responded, “Oh no, let him stay there. If he dies, it will be great publicity.”

Was that a literal nuance or just a taste of his sardonic humor? In 1994, Rubin (who’d paid $85,000 personal income tax the year before) met another Jerry Rubin (a peace activist who lived in Venice, made $6 an hour potting orchids and had $2 in the bank). Yippie-Yuppie said, “Gee, people think it’s me who’s broke. That’s not good. I’m running a business, and I can’t have that perspective.” So he made an offer: “Hey, I’ll give you $10,000 if you change your name to anything — and $20,000 if you change it to Tom Hayden.”

This review originally ran in the Los Angeles Times.