In 1981, I began teaching at a village college just outside Cambridge, and lived in Trumpington, a couple of miles from the town centre.

Typical of many such streets in Cambridge, our house was a part of a row of terraced dwellings. Trumpington was inhabited by a mixture of academics, young professionals (the term “yuppies” was just coming into vogue), and older, mainly retired, working-class families, nearly all of whom had worked for the university.

These working-class families were starting to be priced-out of places like Trumpington, as Cambridge was embarking on a trajectory that would make it the UK’s Silicon Valley, with the usual accompanying exorbitant housing prices.

A couple of houses from us lived John “Jock” Cronin. He was a Scotsman born in Glasgow, a widower, in his 90s, living on his own. He had a daughter who lived some distance away, and she visited him every year or so. Before I got to know Jock, I’d see him shuffling arthritically up and down the street.

My then wife happens to be Scottish, and she enjoyed the company of Jock, as did I. He was lonely, and dropped by often for a chat and a cup of tea. Age had devastated his eyesight, so watching TV or reading were now beyond him. Even glasses could not improve his vision, and I would sometimes read him the front page of the Guardian and the Cambridge evening newspaper.

Long retired, Jock had worked as a gardener for the university. He always preferred to talk about the present, especially politics, and had an abiding hatred for Margaret Thatcher, which was rare for an elderly Brit. Jock was a staunch socialist, and needless to say, this established a bond between us.

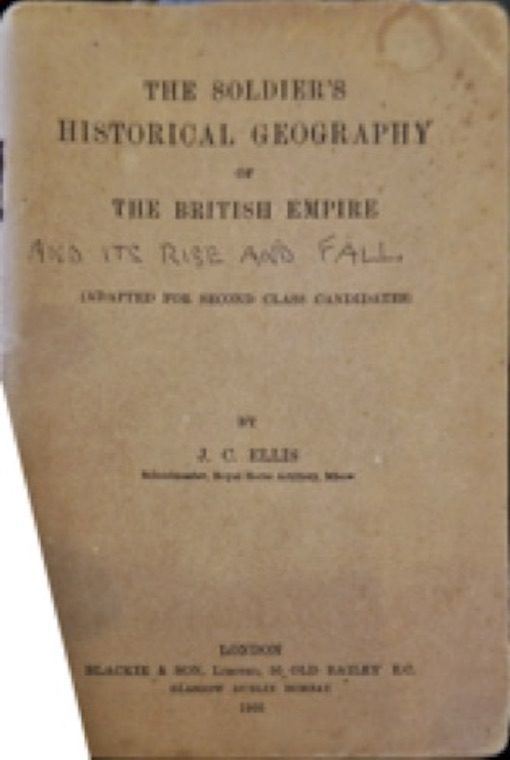

It took time to piece together Jock’s story. He had joined the army in the early 1900s. A book he gave me, titled The Soldier’s Historical Geography of the British Empire (1905), had the following inscription inside: “J.A. Cronin, Talavera Bks, Aldershot, 1909”. Jock, although he had served in both world wars, was an anti-imperialist, and had added “And Its Rise and Fall” to the book’s title (see photos below).

Jock survived WW1, despite serving in some of its worst arenas. The recent commemoration of the centenary of the Battle of Passchendaele (July to November 1917) reminded me that Jock was a corporal in the trenches at Passchendaele, where 244,897 British soldiers died (estimated German casualties were even higher).

The recent commemoration of Passchendaele also spurred me to write this little recollection of Jock Cronin.

Jock also took part in the retreat of General Gough’s Fifth Army in the spring of 1918, prompted by a strong German offensive led by General Ludendorff. One of the books he gave me was C.R. Benstead’s 1930 account of this retreat. It contains a map of the retreat, with Jock’s 9th Division marked, in the top righthand corner, with a circle and the word “Scottish” in it. Several places on the map are marked with cross (see photo).

More startling for me were Jock’s drawings in the book—these were of explosions and a large cannon with a shell still in it, probably evoked by his reading of Benstead’s book a dozen or more years after the retreat of Gough’s army (see photos below).

Jock rarely talked about the war, even though he was an excellent raconteur. I didn’t probe too much either. When he did talk about the war, it was in simple exclamations such as “horrible!” and “terrible!”. I once asked him what was the worst part of it for him, and he replied, “the bombardment, and the rats– there were more of them than us and the Germans!”

Jock also served in WW2. Too old to be on the frontline, he was a convoy driver in a supply regiment.

He was never one for regimental reunions and commemorative parades. I once asked him what he did with his medals, and he said they were in a box somewhere in the house.

Jock was barely able to look after himself, but was too stubborn to enter any kind of assisted living. Virtually blind, he could no longer use his cooker, so my ex-wife and I fed him whenever we could, with soups and sandwiches. He said his ingrowing toenails were “giving him hell”. I was in my early 30s then, and had no notion of how painful these could be. I got them in my 50s, and felt remorse when I thought about Jock– I should have offered to cut his toenails.

In 1983, I got a job at what is now the University of Gloucestershire, and moved there. Every few weeks I would make the drive to Cambridge to attend seminars and lectures at the university.

On one occasion, I drove down our old street, hoping to stop in and see Jock. There was a “for sale” sign outside his house. I stopped and asked a neighbour where Jock was. “He died a couple of months ago”, she replied.

Kenneth Surin teaches at Duke University, North Carolina. He lives in Blacksburg, Virginia.