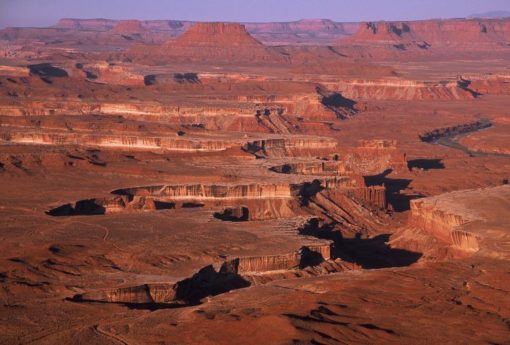

Island in the Sky, Canyonlands. Photo: Phil Armitage.

I am lost in a labyrinth of stone. I only know I must go down. I must follow the striated pink slickrock. Down and down this narrow side canyon, disoriented by an elegant confusion of landforms: arches and hoodoos; dry falls and rock shelters; graben and needles; rimrock, chimneys and swells.

Each step down the canyon takes you back in time. The place seems ageless. But the terrain changes day by day, shedding pieces of itself. It is a paradox of the landscape: the river plays the role of both geological architect and archaeologist: unearthing and altering the shape of the Colorado Plateau on a scale both massive and intricate.

Any attempt to understand the desert Southwest forces you to confront stark complexities, both ecological and personal: the meaning of its openness and silence; the green course of swift rivers in an arid, red land; the genocide and enforced poverty still pressed on its native peoples; the violent rush of rage that overcame me one night walking in the wild desert of the Santa Catalina Mountains at the sight of the lights of Tucson, burning a like a perpetual explosion on the dark horizon.

My goal today is the confluence of the Colorado and Green rivers. I don’t give a damn that I might be off track. The solution is obvious: go down slowly until you meet the river. I walk in a tumbleweed manner, stumbling over rocks. The heat is oppressive, weighing heavily on my stamina, pampered for years by the cool, maritime climate of western Oregon.

Here the air is thin and flat. The humidity hovers at an impossible two percent, sucking the moisture out of you. My lips chap, crack, bleed. They say the unrelenting glare of the sun reflecting off the red bones of rock can flip your consciousness as slyly and absolutely as any hit of mescaline. I open myself to it.

In a state of near delusion, it strikes me that the Southwest is writhing, sexual landscape. Here the landscape exposes itself in mesas, pinnacles and sinuous slot canyons; in the flesh and blood tones of the sandstone; in the cool, lime-colored light of the ponderosa forests (what’s left of them); and the unrepressed exuberance of the desert suddenly in bloom. Here the land seduces the senses.

I am far from the first Anglo to make this obvious connection, naturally. One of my favorite writers, D. H. Lawrence, spent many years in Taos and several more traveling through Mexico. He was enthralled and repelled by the “blood nature” of the desert. Terry Tempest Williams writes arrestingly about the “erotics of place.” The paintings of Georgia O’Keefe-her stunning landscapes of canyons and mesas near Abiquiu, not the overtly sexualized flowers-vibrate with a consuming passion. Elliot Porter’s photographs, especially those of the lost Glen Canyon and the rugged crenellations of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains near his home in Tesuque, evoke similar sensualities.

The fact that we come to this realization as a kind of epiphany is a sad measure of how far we’ve removed ourselves from the rhythms of the land. The native people of the Southwest never knew such distance from the living landscape. Black Mesa and the strangely blue Chuska Mountains are not merely metaphors of the female and male deities for the Navajo, but tangible places of creative powers-as Mount Graham is to the San Carlos Apache, despite the gross indignity of a deep space telescope on the crown of the holy mountain. Similarly, the sipapu (the hole in the ground from which “the people” emerged) entrenched near the center of every kiva built by the Anasazi and their descendents in the Pueblo tribes is quite literally understood as a vaginal passageway of the sensate Earth.

The ragged sound of thunder shudders across the sky. That a slot canyon is a dangerous place to find oneself in during a sudden rainstorm is apparent even to an alien forest dweller like me. I scramble up the sun-warmed Cedar Mesa sandstone to a ledge about 50 feet above the creek bed.

Lightning fissures down out of a single, bruise-colored stormcloud embedded in a sky of absolute clarity. There is a small rock shelter a few hundred feet up the canyon, a perfect cover to ride out this tempest in the desert.

As a cool rain begins to fall, I notice that the slanting wall of the cliff is covered with petroglyphs.  Dozens of pictures and symbols, ghost stories carved into rock. Some are clearly recognizable, others ancient and mysterious: bighorn sheep, coyote, lizards, the initials CJ ’91 deeply chiseled with sophomoric bravado on top of a strange spiral 500 years old, men on horses in conquistador-style hats, circles within circles, tiny red handprints, floating armless, near-human figures.

Dozens of pictures and symbols, ghost stories carved into rock. Some are clearly recognizable, others ancient and mysterious: bighorn sheep, coyote, lizards, the initials CJ ’91 deeply chiseled with sophomoric bravado on top of a strange spiral 500 years old, men on horses in conquistador-style hats, circles within circles, tiny red handprints, floating armless, near-human figures.

A familiar image haunts the lower portion of the panel, the proud sign of an archaic fertility symbol etched into the dark desert varnish that coats the sandstone walls like a swipe of dried blood. Yes, it is Kokopeli, the hunchbacked flute-player, his wild hair standing up straight like the antennae of an insect, his engorged phallus cocked at an assertive and defiant 45 degree angle. He is the ubiquitous kachina of the pueblo people, who, in their wide migrations, have left his image on rock walls from Tierra del Fuego to northern Alberta.

This petroglyph panel is a historical tapestry of the Southwest woven onto stone-a silent meeting place for the rich diversity of people who have lived upon this land, a place where cultures speak across centuries.

* * *

I finally reach the Colorado. But bad memories flood back. The last time I touched its waters was on a rented houseboat, rendered nearly senseless by a dozen bottles of Negro Modelo, floating above the blue void of Lake Powell.

Lake Powell: a place people come to inebriate themselves against the violence that has been done to the land. It is even a Mecca, of sorts, for radical environmentalists, a place we gather to vent our sour nihilism. Glen Canyon Dam: the objective correlative for every foul damn thing we’ve been doing to this country all these many years.

Yet, there is an undeniable, if repulsive, beauty to the dam itself: its cool sweep of blonde stone, its arrogant assertion of blind power over the forces of nature, the old, inescapable themes of dominance and submission. A fascist architecture that would humble Albert Speer himself.

Glen Canyon Dam is there for a reason, a reason that exposes the tragic flaw in environmental politics. David Brower’s admonition that environmentalists “never trade a place you know for one you don’t” came through bitter experience. Brower himself crafted the deal that doomed Glen Canyon as a way of saving the stunning canyons of Dinosaur National Monument.

And the compulsive pattern of dealmaking persists. The trade-off for a free-flowing Colorado through Marble Canyon was more nuclear power plants and uranium mining. And the construction of the foul power plants at Page and Four Corners that burn coal gouged from the heart of Black Mesa and spew out the fly-ash in black stains visible from the international space station. Go to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon where, even on a good day, the view has been drained of color, smudged. It’s like look at the great chasm through a funeral veil. What the hell have we done?

Power follows property, said John Adams. And so it does. But in the desert Southwest, property follows water. Here water is power. Geronimo knew that well, recall his dazzling defenses of places like Apache Springs. The sexual predator and water-vampire Floyd Dominy (the J. Edgar Hoover-like head of the Bureau of Reclamation during the glory days of dam building in the arid west) grasped the political power of water. So did Mo Udall and Bruce Babbitt, whose reputations as “conservationists” will be forever darkened by their obdurate support of opulent water stealing schemes such as the Central Arizona Project. Impound the water and tame the electorate is the numbing mantra of Southwestern politics.

Follow the money, Deep Throat advised. In the Southwest, if you want to divine the truth, follow the water. Sooner or later you’ll end up at a cow. More than 80 percent of the water diverted from the Colorado River goes for agricultural irrigation. And that means cattle. The water goes largely to multi-millionaire ranchers and ranches owned by transnational corporations and banks. The water no longer goes to the rural Hispanics, Apache, Hopi and Navajo, who had developed a truly sustainable grazing and small agriculture based on the ancient system of acequias other indigenous irrigation systems.

The ancient Hohokam village known as Los Muertos was served forcenturies by a six-mile long canal diverting water from the Salt River to corn and squash fields. Eventually, a 30 year drought struck the Southwest. The Salt River dried up and even the gentle agriculture of the Hohokam overtapped the dwindling resource. The city was abandoned.

Marc Reisner observes in his indispensable book Cadillac Desert that that same problem afflicts the entire Southwest today. But it is a problem that has been engineered in less than 50 years, not a millennium. The technological uses of the Colorado River are killing the land at both ends: through the submersion of places such as Glen Canyon and Flaming Gorge and the salinization of millions of acres of irrigated farmland in an arid climate. Watering the desert didn’t transform Arizona into Iowa, but rendered it into a kind of post-modern Carthage. Technology wounds, says New Mexico writer Chellis Glendenning. In an arid climate, the wounded land heals slowly, bearing deep scars that defy concealment.

In the end, the transfer of water is a transfer of power, property and wealth. The infuriating entanglement of western water laws is a deliberate confusion, a well-designed impediment to the to the appropriate and equitable allocation of resources, to real land reform and to the preservation of the desert rivers themselves. While the obstacles to such an ecological revolution may be profound, the way back is simple: Make the water stay with the land.

* * *

It tells you something about the politics of the Southwest that one of the wildest places in the region is the White Sands Missile Range. But it tells more about the macerating nature of cows. Patriot missiles don’t pack near the wallop on the ecology of the desert as a bovine herd grazing on full-automatic.

One of the main problems with domestic livestock grazing is its omnipresence on the landscape. More than 96 percent of the publicly-owned lands in the Southwest (excluding the national parks and military lands) are under grazing permits. No place is immune. Note even the world’s first wilderness reserve, the Gila Wilderness Area, can escape the scourge of cows, stock tanks and ranching roads. These days real cowboys ride Chevy trucks, not palominos.

The impacts of grazing on desert wildlife are staggering. According Grazing to Extinction, a report written by ecologist John Horning, grazing the primary cause of decline in the populations of 76 species of fish and wildlife that are either listed or candidates for listing under the Endangered Species Act. And cows and sheep are a contributing factor in the slide toward extinction of at least another 270 species. This is not to mention the bloody toll exacted on fragile populations of desert predators by hired killers from Animal Damage Control for the psychic benefit of western ranchers.

The cherished myths of the west are engraved so deeply on our consciousness that our perspective of how the land should look is distorted in unexpected ways. For example, many of us raised on the films of Howard Hawks and John Ford assume as a matter of course that the rock-strewn, barren banks are the natural aesthetic conditions of rivers such as the Rio Grande and San Juan. In fact, the rivers of the Southwest should flow through verdant sleeves of willow and cottonwoods trees. The fact that these riverine forests were largely eliminated from the landscape by the 1930s without, for the most part, ever suffering the bite of a chainsaw, illustrates the devastating consequences of livestock grazing on ecological fragile riparian areas.

Some of what has been lost is nearly unseen, but may be critical to the functioning of the desert system itself. Take cryptogamic crust, a kind of blue-green algae that weaves through the desert floor in thin black webs. The cryptogamic crust is the connective tissue that holds the desert together, similar to the mychorrizal fungi that underlies and nourishes the ancient forests of the Pacific Northwest. But this “living soil” is destroyed by intensive livestock grazing, permanently impairing the ecological capacity of the land. Now extensive patches of cryptogamic crust can only be found only isolated mesa tops or in ungrazed parklands, such as Arches or the Maze district of Canyonlands.

Sooner or later the deconstructionist of western myths must take on the rancher and the folklore of the rugged individualist. There is a particular subspecies of the western rancher who remains blithely ignorant of the fact that his “lifestyle” is maintained by the generosity of the same federal government he despises. The average ranching family in the Southwest receives more than $25,000 a year in federal subsidies, yet squeals at even the most modest attempt to reform grazing practices on federal lands as an attack on inviolate property rights. The historian Bernard DeVoto best captured the attitude of the welfare rancher toward the federal government: “Get out, and send us money.”

What has changed since DeVoto’s time is the increasingly hostile demeanor of the ranchers and the object of their aggression: environmentalists have replaced the feds as the new target for cowboy angst. One of the most violent epicenters in the backlash against environmentalism is Catron County, New Mexico, which my friend Karl Hess Jr., the libertarian environmentalist and author of Visions Upon the Land, calls “Cartoon County.” And indeed it would be funny, if the reality were not so vicious. Here a brutal paranoia has spread like strange virus from 1950s science fiction film. The ranchers of southern New Mexico and Arizona have become bitter allies in a violent campaign against local environmentalists, who have become the scapegoats for all of their financial, social and sexual problems.

The ranchers have adopted the litany of victimology. And some of them may indeed be victims. But not of environmentalists. The real agents of their misery, such as it is, are the banks squeezing their mortgages and a government that promised them more than the land could ever deliver.

“The war on the West may be a media event,” says my friend Pat Wolff, a longtime veteran of the environmental wars in the Southwest. “But the climate of violence in New Mexico and Arizona is real. And it is intense. The scary thing is the level of tolerance given to the violent outbursts of ranchers, loggers and miners.” Like many environmentalists in the region, Wolff was regularly threatened-often in public. Rarely are the threats investigated and often the most virulent ranchers are portrayed as iconic figures in the local media. In 1993, my friend, the Navajo environmentalist Leroy Jackson, was found dead in his car on the Brazos Cliffs in northern New Mexico. He was on his way to Washington, DC to testify about the logging of sacred lands in the Chuska Mountains. His death was almost certainly the result of foul play. The cops didn’t even launch an investigation, ruling his death a suicide. The dangers are real.

* * *

The conquest of the Southwest began with the search for gold and rapidly expanded to baser minerals: silver, copper, uranium, molybdenum, coal. Shafts were dug and blasted into nearly every mountain range in the region. Some mines ran for decades, others ran out in months.

What the mining companies left behind were not the ruins of a vanished culture, but a toxic legacy of greed-a gored and disemboweled landscape heaped with tailings piles and mining wastes, the foul detritus of the private engorgement of the public’s lands, left to leach for decades into the Southwest’s precious waters.

The violence wrought upon the land accompanied a similar violence inflicted on the native people of the region. It began, of course, with Francisco Vazquez de Coronado’s storming of Zuni Pueblo in 1540, mistaking the sun-burnished adobe walls for the golden city of Cibola. His marauders were vigorously repelled by the Bow Priests of the Zuni. Pueblos 1; Entrada 0.

But the Spanish didn’t relent. One by one the pueblos fell to Spanish control. By 1598 each had been conquered, all, that is, except for Acoma, perched on its high mesa in western New Mexico. The following year the power-maddened Juan de Oñate ordered his troops out with instructions to subdue Acoma Pueblo. The Acoma people greeted the conquistadors with corn-pollen and turkey feathers. But the Castillans demanded tribute; they demanded gold. When the Acoma refused, the Spanish killers corralled the men, chopped off a foot from each (500 in all) and pitched the tribal leaders over the steep cliffs to their deaths.

It didn’t end there, of course. In 1863, when the gold and silver miners demanded free access to the mountains of southern New Mexico and Arizona, federal troops were sent out to annihilate the Apache, who had refused to settle on reservations. Smithsonian “collectors” accompanied the troops. They photographed the mutilated bodies of dead Indians, decapitated the heads, marked the skulls and sent them packed in boxes back to Washington. The great Apache leader Magnus Colorados was finally captured, publicly bull-whipped and murdered. General Nelson Miles led 5,000 soldiers in the final pursuit of Geronimo and his 37 warriors. The rest of the Apache were forcibly relocated to reservations, managed for decades as concentration camps.

The oppression continues, but in more insidious ways. Tribal councils are infiltrated by government snitches and corporate stooges. Budgets are bankrupted, resources exhausted. Thousands of Navajo are forcibly evicted from Big Mountain, while Black Mesa, their sacred mountain, is strip-mined by Peabody Coal. The tribal forests are logged at a voracious pace under the lash of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Mescalero Apaches are offered a nuclear waste dump as a way to enhance their “quality of life,” as the San Carlos Apaches have their sacred Mt. Graham desecrated by the construction of deep space telescopes. Religious concerns about the sacred nature of Mt. Graham are dismissed as “primitive” emotions and opponents are smeared as part of a “Jewish conspiracy.”

The rural Hispanics of New Mexico have been victimized by a second conquest as brutal and oppressive as that conducted against the Pueblos, Navajo and Apache. Land claims have been abrogated; water rights stolen. Since its earliest days in the Southwest, the Forest Service has used the rubric of “conservation” as a pretext for the acculturation of Hispanics and the dispossession of their property and their basic rights to use commonly-held lands. A modern day enclosure movement. Urban environmentalists share some of the culpability for these past wrongs.

In fact, all of the federal land management agencies have placed a template of homogeneity over the Hispanic people of the region-the cultural equivalent of even-aged management. To date, there have been few efforts to redress these abuses. No reparations have been paid. Little land has been returned.

This wretched history of conquest is ameliorated only by the enduring beauty of the landscape and by a persistent culture of resistance, a spirited defense of the land that dates back to the first stream of arrows launched at Coronado by the Zuni warriors in 1540 and continued through Reies Tijerina’s 1968 raid on the Tierra Amarilla courthouse in an attempt to assert land and water rights granted but never honored in the Treaty of Guadeloupe Hidalgo to the Apache Survival Coalition’s vigorous defense of Mt. Graham from the rampages of the University of Arizona and the Vatican. Radical environmentalism was born in the deserts and rivers of the Southwest: Aldo Leopold, Black Mesa Defense, Ed Abbey, Doug Peacock, Earth First!, and El Partido Verde, a political movement linking progressive environmentalists with other social justice movements.

* * *

The town is Nuevo Casa Grande in the Chihuahua province of northern Mexico, 100 miles or so southwest of El Paso. It is an old place with a new name. We are sitting outside a dusty cantina made of mud the color of salmon flesh. The finger traces of its builders streak the walls. The window and door frames are turquoise, the paint peeling off in blue scales.

The waitress has left us dark bottles of home-brewed beer and basket of chile peppers, poblanos and serranos, little green sticks of dynamite. We eat them until our mouths are enflamed with an exquisite pain.

Some ethnopharmacologists swear that you can hallucinate this way. But being novices, and wanting later to amble in a nearly erect manner across ancient ruins outside town, my friend Fremont and I decide to linger on the bright edges of consciousness, here in this beautiful and tragic place, where macaws in wicker cages hang above us like cackling white blooms. These birds of the jungle were sacred to the Anasazi, Hohokam and other people of the northern desert. I have seen petroglyphs of macaws carved into pink sandstone cliffs high above the San Juan River in Colorado, a thousand miles away from the nearest rainforest.

The complexities of these ancient trading networks are astounding to me, but they shouldn’t be. The indigenous culture of Mexico was ever bit as advanced as the Egyptians or the Athenians. More advanced in many ways, particularly in its relatively benign relationship to the land.

We are waiting on a man to lead us through Paquimé, the large complex of ruins of one of the most sophisticated cities of pre-Columbian America, located a few miles outside town. For nearly 1,000 years, Paquimé was the ruling cultural and political center of northern Mexico. It was the nexus in a vast web of trade and commerce that extended in a 500-mile radius. Its architecture and agronomy practices were exported north to the Mimbres and Pueblos of New Mexico and Arizona. So were its macaws. In fact, the breeding and trading of birds may have been the main source of wealth for this city of 20,000.

A wind blows from the east. The fumes from a Pemex plant invade the air. It is a suffocating sensation, with each breath a black clotting of the lungs. Finally, an archaic truck rattles to a halt in front of our table. A small, wiry man climbs out of the driver’s side window. His dark face is fissured with wrinkles. He has a beautiful smile. He has no teeth.

His name is José Lopez. He is a mestizo from Oputo, a small village on the Rio de Bavispe, 70 miles to the west. He has worked many jobs. He says he has logged timber in the Sierra Madre for Champion, International. He has stitched soles on running shoes, getting $2 for a 14-hour day. He worked in the Pemex refinery, until he fell and broke his back. It has almost healed, he says. Now he does odds and ends. He leads tourists to Paquimé. He speaks English. He is 78 years old.

We climb in the back, careful not to put too much weight on the truck bed’s thin crust of rust, and rumble down a narrow dirt road, casting behind us a billowing plume of smoke and dust. We watch the chilling disparities between life in rural Mexico and rural New Mexico, one of the poorest regions in the US, unscroll before us: children huddled on the roadside under red, woven blankets; women carrying wooden buckets of water taken from the hideously polluted Casa Grandes River for miles to tin shacks in barrios beside open sewers; men working the dry beanfields under a blistering sun.

The Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa called Mexico “the land of the perfect dictatorship.” It is a dictatorship that has been created, propped up, anointed and rewarded by the US government for nearly a century, ever since Black Jack Pershing busted across the border in 1917, vowing to bring back Pancho Villa “in an iron cage.”

We have logged their forests, drained their oil fields, fixed their elections, threatened to seize their treasury, send them our sweatshops, our drug financiers and maquiladoras. For the last decade or so NAFTA has been at work, grinding away at the Mexico’s poor and indigenous people. In return, we have sealed our border against the “scourge of brown immigrants.”

José brings the truck to a halt on the crest of a small hill overlooking a sprawling labyrinth of stone structures. The hill itself, José says with a slightly creepy edge to his voice, is a ceremonial mound. The ruins of Paquimé are thirty times the size of the celebrated Pueblo Bonito at Chaco Canyon, the largest Anasazi site in the American Southwest. Paquimé once featured condominium-like structures six stories tall, dozens of Mayan-like ball fields, temples, warehouses, marketplaces and plazas. Now it is empty and crumbling, a city of ghosts.

We descend into the ruin, passing down narrow corridors and steep staircases to a subterranean layer, more than 10 feet below the surface. Around 1350, Paquimé was hit by a series of catastrophes: an earthquake, a meteor strike, and finally, a vicious attack by a well-armed enemy, perhaps the Aztecs. The city was abandoned by 1400 and never reinhabited.

José is telling the story of Paquimé in a vault that once stored beans, squash, chiles, peyote, and maize, when we are startled by a hollow buzzing, an insect sound, like the drone of a cicada. José motions us to stay still, while he performs a strange ballet across the floor into a dark corner of the room. Moments later he emerges into the filtered light holding a pure white rattlesnake, its tail twisting around his thin forearms. (Did he keep it here to impress the tourists? A conjuror’s pet? If so, it worked.)

José rubs the flesh of the rattlesnake against our cheeks. This is not a ritualistic act, but an offering of experience. The snake is warm and smooth. I can feel the beating of its heart. Then José places the snake on the cold stone floor. It coils, then uncoils and vanishes into the fractured wall. José lights a cigarette and coughs. “It’s all going to go as it did before,” he says. “First the Indians, then the forest.” Then he leaves us, alone in the deep silence of the sandstone ruins.

* * *

The libertarian economist John Baden used to quip that “even God wouldn’t try to grow trees in Utah.” The same maxim can be applied to the rest of the Southwest. You can cut down the primary forest, but you’ll have a helluva time getting it to ever come back. There are 500-acre clearcuts on the Carson National Forest in northern New Mexico (one of the moister parts of the region) logged in the early 1960s where the replanted trees remain shorter than your shoulders. It’s a dry land and it’s getting drier.

Desert forests, the green embroidery of the Southwestern landscape, are intimately tied to two features: water and elevation. The abstract concept of biological corridors is vividly expressed here on the face of the land itself, as the riparian forests (what’s left of them) form thin veins through the vast deserts, linking the denser forests of distant mountain ranges. In the Pacific Northwest, the lower you go, the bigger the trees. That trend is reversed in the Southwest, where the deep forests of Mt. Graham float on a sky island a mile above the Arizona desert.

These factors create complex forest ecosystems that are extremely vulnerable to external influences, partially accounting for the paucity of old-growth in New Mexico and Arizona. In fact, the only region of the country with less old-growth forest than the Southwest is the southern coastal plain, now on its fourth generation of monocultural plantations.

Of course, the main reason the Southwest lacks old growth is the mission of the Forest Service, which has waged a vicious attack on the region’s forests for the past 40 years. On the surface, the agency’s timber sale program appears to be an exercise in economic irrationality, since it loses nearly $10 million every year. In reality, of course, this largesse translated into corporate entitlements for companies like Duke City Lumber, Kaibab Forest Products and Stone Forest Industries, whose mills served as the charnel houses for the forests of the Southwest, annually grinding up about 500 million board feet of public timber.

The presence of any significant chunks of old-growth in the Southwest today is largely due to the determined efforts of two tireless environmentalists: Robin Silver and Sam Hitt. Using the declining populations of Mexican spotted owls and northern goshawks as a legal wedge, Hitt and Silver teamed up with a pair of courageous scientists, Cole Crocker-Bedford and Peter Stacey, to craft a barrage of appeals, lawsuits and Endangered Species Act petitions that eventually paralyzed the agency into something like submission.

Meanwhile, the “managed” forests of the region are sprucing up. And I don’t mean they are getting cleaner. Less than a century ago, the forests of the Mogollon Rim, for example, were among the most exquisite on the continent: cool and open stands of big yellow-bellied ponderosa pines. Today these forests have been transformed into a cluttered thickets of spruce and piss-fir. It is the old story of mismanagement played out on a bioregional scale: grazing, high-grading and fire suppression.

The ecosystem has been terraformed, inverted almost. But the forest is aiming to right itself of its own volition. The fuel is building up. The fires will come. There will be no stopping them. And the once and future forest will rise up out of the ashes like a true phoenix. Burn, baby, burn.

* * *

Once again I am drawn back, almost as if down the pathways of a dream, to the image of Old Oraibi at dusk, a dark mesa in an ancient light. Oraibi, sacred city of the Hopi, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America. Here a complex society and agriculture co-evolved with a parched landscape of sand and stone. Here is a community that has sustained itself under the harshest conditions of nature, internal strife and cultural aggression. The survival of Oraibi derives from a cultivated wisdom about the desert, an intimate knowledge of its limitations and capabilities.

“Together we realize the dangers of losing our land and our culture,” the late Hopi elder Thomas Banyacya told me years ago. “We must come together will all people to protect this land or it will die.”

There are answers here to questions I have not yet learned to ask. They involve the nature of paradox: pacifism and resistance; despair and hope; poverty and wealth; change and tradition; freedom and responsibility; wilderness and community.

Standing at the base of Oraibi as the orange sun eases below Third Mesa, I am overwhelmed by the irresistible power of this place, by a fierce love for the land, by an unyielding desire for justice for its people.

This essay is adapted from a chapter in Born Under a Bad Sky.

Booked Up

What I’m reading this week…

The Other Slavery: the Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez

A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell by Donald Worster

The Rock Art of Utah by Polly Schaafsma

Sound Grammar

What I’m listening to this week…

Way Out West by Sonny Rollins

A Little Bit is Better Than Nada by Texas Tornados

Acoustic En Vivo by Los Lobos

Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger by Bo Diddley

Perdóname Mi Amor by Los Tucanes de Tijuana