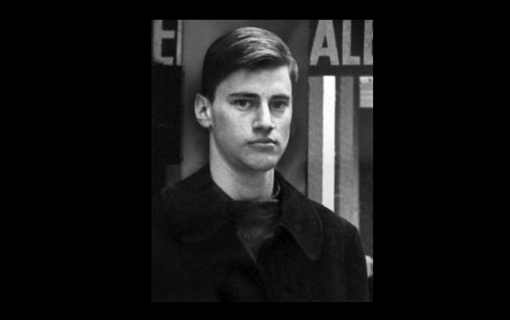

Photo by Jimaize | CC BY 2.0

Ella: That cat’s tearing his chest out, and the eagle’s trying to drop him, but the cat won’t let go because he know if he falls he’ll die.

Wesley: And the eagle’s being torn apart in midair. . . .

Ella: And they come crashing down to the earth. Both of them come crashing down. Like one whole thing.

Curse of the Starving Class

“…once in a while I’m just amazed when I catch a glimpse of who I really am . . . And I ask myself, ‘where have I been all this time? Why was I blind?”

Sleeping at the Wheel

Sam Shepard once described his arrival in NYC this way: “It was wide open…You were like a kid in a fun park”. That was toward the start of the sixties. I met Sam in 71 I think it was. I came to stay with my cousin Jim Storm in his 5th floor walkup on Christopher St. I was supposed to stay a few days but I stayed six months. I returned to El Lay but came right back. Jim was in a play of Sam’s, Mad Dog Blues. He played a character based on playwright Murray Mednick (as I recall anyway).

Not all that much had changed since the early sixties. But it was starting to. Shepard was nice to me, as was his then wife O’Lan. And Mednick, who was later to become my greatest teacher in theatre. I have a vivid memory of meeting Sam and Murray and Leroy Logan at a dive on the lower east side my first night in New York. The Blue and Gold I think it was called. I thought, well, this is exactly what I was looking for. I sensed, rightly, that something of importance was going on with the off off broadway scene. As it turns out, it was in many respects the last genuine movement in theatre that America was to have. And Mednick and Shepard were both at Theatre Genesis, about which Irene Fornes once quipped…’oh all those neurotic straight men’.

I saw Sam a lot in those days. But we never talked that much. Still, he was always encouraging to me. He was unfailingly generous to young writers. Later, we did the Padua Hills Playwrights Festival together where Sam came for the first two years, as I recall. Padua was a kind of profound post script to ‘off off’, but with a western left coast sensibility. And really, Sam was always a westerner. His writing was western.

“The California I knew, old rancho California, is gone. It just doesn’t exist, except maybe in little pockets. I lived on the edge of the Mojave Desert, an area that used to be farm country. There were all these fresh-produce stands with avocados and date palms. You could get a dozen artichokes for a buck or something. Totally wiped out now.”

Sam Shepard

Interview Paris Review

This is important I think. He may never have lived in California again, but California never left him. And it is maybe that which attracted me. The off off broadway scene, whether at Genesis, or La Mama or Judsons was not institutional theatre. There were no MFA playwrights there. But many of those talented even visionary writers were exiled from the American stage. Last time I saw Ronny Tavel he came to a workshop I was conducting in LA, where he was visiting for a few days before returning to Taiwan where he taught English. He was surprised I knew and loved his play Boy in the Straight Back Chair. Many of those off off actors worked at Padua. But the energy was hard to sustain. But Mednick ran the show at Padua for 15 years. A Herculean feat in a disintegrating cultural climate.

I can’t write a critical analysis of Shepard’s work here. Others have done so. Though whenever I read them I feel as if they are trying to domesticate his work somehow. Sometimes they feel, maybe unfairly, like parodies of academic analysis. Shepard’s work just doesn’t lend itself to the professorial voice. For the single most intractable quality is that of unruliness, transgression, and the desire to unlock that hidden history of U.S. culture and society. It is the history one finds in early blues and country music. His plays contained pop elements but they were always there in some disfigured and malignant way. And his plays are sincere. Something of a bad word these days. Shepard’s writing is not ironic. It aspires to a kind of tragedy. Killer’s Head, which I saw for the first time with Ed Harris remains a singular monologue. It is rather perfect theatre and I say that having said before that one character plays are never really theatre. But that’s the thing, too. Shepard’s work IS theatre, but it is also something else. Something elusive and furtive and incantatory. And it breaks rules, almost as a habit. Or an obligation.

I remember being at Padua one summer when people were talking about Sam being off doing this movie. Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven. Nobody said it, but it felt a bit like Dylan going electric. Speaking of which I once worked on a film project for Dylan, on the California Gold Rush (a project that lasted a few weeks at most) and he talked about Sam. He loved Sam. But that trip to Hollywood marks the end of the first stage of Shepard’s writing. And Sam himself said it was hard to write sitting in an actor’s trailer on set. Still, the rock n roll side of Shepard is linked to the Hollywood side, and that, in retrospect, becomes a complex topic. The cultural landscape of the U.S. was changing. A generation of artists in New York were devastated by AIDs, and there were no mayors like John Lindsay throwing money at the arts. And the money that was thrown was not going to places like Theatre Genesis or the like. It marked the start of the mass bureaucratization and administration of arts and culture. That fun house Sam described no longer existed. 42nd street got cleaned up, and the arts got sanitized about the same time.

I ran into Shepard another time, in LA at a bookstore. He asked me to pick a book for him and I said ok, but you pick one for me, too. He gave me Franz Xavier Kroetz’ Farmyard, and I gave him Heinrich Von Kleist’s short stories. He was a voracious reader but pretended not to be, sort of. The New York of the 60s and even 70s was gone, the California of post WW2 was gone. And Shepard retreated to his property in Kentucky, or Virginia, somewhere, and to Hollywood. In a sense it is a curse to find too much success in the wrong ways. Shepard struggled to write significant plays, serious plays, in an atmosphere that less and less wanted such stuff.

His was a voice that straddled classes and penetrated the well manicured stages of Lincoln Center and the Royal Court. But that work was never quite at home in those places. I saw States of Shock, in 92 I think, a neglected play of his, at the American Place Theatre, with John Malkovich and Michael Wincott. It was an anti war play of sorts. But it was more about the fetid psyches of those manufacturing war, and a kind of autopsy of the validity or not of sacrifice. And it was again a play that refused to adhere to structural expectations.

The rock n roll side of Shepard was in that refusal to think the way they teach in writing workshops. Rhythm came before form. But this was always a textual theatre. Somehow this, too, is forgotten these days. The dialogue is always so good that one almost feels shamed, to be not good enough to listen to it rightly. When Adorno said “wrong life cannot be lived rightly”, he was talking about art. Or about art first. Sometimes you cannot *hear* it rightly enough. I have felt that way with Handke, too, and with Pinter. I once had a class (sic) and the discussion turned to a comparison of Pinter, Shepard, and Mamet. The conclusion was that Pinter and Shepard were superior, and they were superior because they were metaphysicians.

“…everything was wonderful, the front lawns were all being taken care of, there was a refrigerator in everybody’s house. Everybody had a Chevy, and these guys had just been bombing the shit out of Germany and Italy and the South Pacific and then they come back; I meant it just must have been unbelievable. I mean nobody ever really talks about that. Back then it was taboo to talk about it. ‘Nobody’s crazy; everybody’s in good shape.’ I mean can you believe it? And this happened across the country of course, but my dad came from an extremely rural farm community—wheat farmers—in Illinois, and next thing he knows he’s flying b-24s over the South Pacific, over Rumania, dropping bombs and killing people he couldn’t even see. And then from that into trying to raise a family and growing up in white America, you know. I mean it’s extraordinary. It’s amazing the way all that flip flops, from the fifties to the sixties. This monster appears. The monster everybody was trying to keep at bay suddenly turns over.”

Sam Shepard

Interview with Matthew Roudane

I saw Sam another time, again in a book store, this time in New York, and it was right after he had won the Pulitzer for Buried Child. I said congratulations. He shrugged and said, ‘Well, that’s the kind of play wins a Pulitzer’. I wasn’t sure what he meant at the time, but now I think I know … or I know more what he meant anyway. It is a great play but it teeters perilously close to being well constructed, in the wrong sense.

When Charles Olson wrote of Melville he was writing of all significant American artists:

“The Pacific is, for an American, the Plains repeated, a 20th century Great West. Melville understood the relation of the two geographies. A Texas painter settled in Brittany and spent his life on canvases of French fishermen and the Atlantic Ocean. But the paint, the motion, the reality turned out to be the Plains. Each canvas was the Panhandle seen through a screen of sea. Space has a stubborn way of sticking to Americans, penetrating all the way in, accompanying them. It is the exterior fact.”

So many great American painters came from the wide spaces of the plains and deserts. Agnes Martin and Clyfford Still, or Pollock. That empty space allows one to see differently. Shepard wrote with that ability to see. Space and the whispers of scalp hunters and Chinese workers, and Manifest Destiny; they inhabit the West. Shepard, for better or worse, was an American writer. Memory seems to take up residence in the West. Shepard’s best work is his most western. And for Sam, that was linked to his ambiguity about masculinity and patriarchy. His own physical beauty played no small part in his success, and he well knew this. He intuited the calculus of cost to the human individual.

There were forays into screenwriting, none of which were really significant. I am personally convinced his work on Paris, Texas consisted of the one great monologue in the film delivered by Harry Dean Stanton. It is as pure a bit of Shepard as one might ever find. But film is not a medium for text.

His work in the early 21st century, in Ireland, with the Abby Theatre, included his best late play Kicking a Dead Horse. In some way, the work in Ireland allowed Shepard to exist outside the spotlight of the cannibalistic U.S. press and the equally cannibalizing American institutional theatre scene. Actor Stephen Rea became perhaps his greatest stage interpreter.

One must exile oneself from one’s home. The exile is the quintessential 20th century figure. And likely, even more, in the 21st. Sam Shepard wrote from a kind of exile, anyway. An exile from home and from self. But home is indelible. Home and space and memory. Sam’s America, which is really the same one I remember from my youth, is gone now. And that quality of lostness permeated Shepard’s work.

Sam’s work cast a long shadow over the American stage. You couldnt find a theatre anywhere in the U.S. in which his name didn’t come up at least once during the day. No college went long without doing a Shepard play. And the later film appearances will likely, and kindly be forgotten. Hollywood has a terrible affect on people. His roles in nakedly reactionary movies like Blackhawk Down will be one of those enigmas, I think, that one simply accepts or forgets. Wrong but also almost incomprehensibly wrong. One pays for such choices in ways that are often mysterious. He grew more uncomfortable looking in the later films. He walked through them and collected his checks (think Bloodlines). His later plays may well turn out to be among his best, though, but for now, as is the case with many artists, the late work is opaque. He was now transcribing something even more complex in the late phase, a subtextual struggle with fame and public personas, and with how to hide, and with societal malaise.

One cannot choose to be the voice of an era. That simply happens and it happened to Sam. Read social media after the announcement of his death and you can feel the desire for so many to participate in the Sam Shepard saga, to share in the sadness of his death, and the darkness of his illness. And reading the obits in places like the N.Y. Times, or the Guardian, is a bit like reading the changes in the American artistic landscape over the last forty years. Other playwrights, usually young and all University educated in writing programs, are quoted. They refer to `Mister Shepard`. And you will read quotes from Hollywood directors on what a *cool guy* Sam was. That word comes up a lot in people writing about him. And that is because the culture has been reduced to style cues. To personality and kitsch. Shepard wrote of that struggle, too. With public perception, with the glossy magazine depiction of life. And his married life to a movie star was a genuine trial for him, I think.

But more than anything he wrote about the trauma to American men, often to returning soldiers. His plays were not overtly political and I suspect his politics were confused. But he was a poet finally, and poets channel something of the truth of the social and historical. The voices he created, for the lonely and damaged men, scarred by war, by failure, and excess, are as true a picture of America as any writer in the century. And they are his real legacy. The story of a violence to the psyche that happens in America. The violence that is embedded in a nation of stoic killers (to paraphrase D.H. Lawrence).

His presence, his shadow, was there to the end. And that is a burden. And a gift.

Now, with his passing, that shadow looms as an indictment.