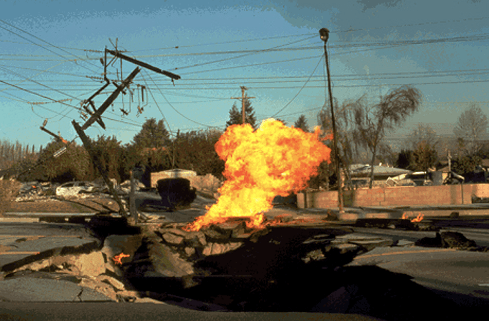

Fire and lateral spread caused by the 1994 Northridge earthquake. The ground in the lateral spread slid to the right, riding on liquefied sediment, and opened the fissure. Extension across the fissure stretched and broke the natural gas pipeline, causing the fire. U.S. Geological Survey. Photograph by M.J. Rymer | CC BY 2.0

Long Beach, California

Porter Ranch residents in Southern California, like the rest of Los Angeles, are sitting on a ticking time bomb.

The Aliso Canyon storage facility, site of the massive natural gas leak in October 2015 that displaced over 8,300 homes and spewed 97,100 tonnes of methane into the atmosphere, could have another catastrophic leak – a leak up to 1,000 times greater than 2015 – when the area is hit with a major earthquake.

That’s the grave warning James Mansdorfer, a former Southern California Gas Co. storage wells and reservoirs manager, laid out in a letter to Department of Conservation’s Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) at a recent LA county court proceeding. Last week California regulators approved refilling the battered storage tank with natural gas. The county, citing Mansdorfer’s concerns, asked a judge to block SoCalGas from re-injecting the well. The refilling is moving forward, ignoring objections from the county, environmentalists and other concerned citizens.

“My belief is that there is potential for catastrophic loss of life, and in light of SoCalGas refusal to openly address this risk, my ethics just will not allow me to stand by without making the public aware of what could happen,” wrote Mansdorfer.

The Aliso Canyon facility is set to be phased out over the next ten years, but a deadly quake could easily strike within that timeframe. Like the rest of greater LA, Porter Ranch, nestled along the fussy Santa Susana fault, is a hotbed of seismic activity. Over 100 earthquakes have struck Aliso since 2006, at least a dozen of which registered magnitudes of 2.0 to 4.7.

Earthquakes, of course, are a normal part of everyday life and geology here in California. There are several major faults running under Los Angeles and Long Beach alone, and a big jolt from any would take a toll on the region’s aging oil and gas infrastructure. Since this should be perfectly obvious, you’d think regulators would want to make sure everything, especially underground gas storage facilities, went through rigorous testing. That’s not the case. There is no requirement for a seismic study to be completed before re-injection of the Aliso Canyon well begins.

Mansdorfer’s letter, which was first reported by KPCC, warned that a large earthquake “would almost certainly sever the casing (and tubing) of every well, resulting in the release of gas at a rate 100 to 1,000 times” that of the 2015 leak.

No doubt a large earthquake under Los Angeles would do more than wreak havoc on the folks in Porter Ranch. The 1994 Northridge quake, which clocked in at 6.7 on the Richter, caused hundreds of fires to break out when gas lines fractured, 35 fire stations were damaged in the shake and six freeways were ground to a halt. LA’s fire department was grossly understaffed, but luckily for them the quake struck at 4:30 AM and not 4:30 PM. Most people were still in bed and not inching along the freeway. The reason the fires didn’t spread and cause more damage was because the winds that early January morning were calm. The outcome could have been much, much worse, taking far more than the 60 lives that did perish.

As Mike Davis notes in Ecology of Fear, “If Northridge was a small-scale trial run for a prospective ‘direct hit,’ Los Angeles failed miserably.”

Not much has changed since 1994.

When LA is hit with a significant earthquake closer to its southern coastline, and one day it will, portions of the hundreds of miles of underwater oil pipes and over 3,000 active oil wells will likely be damaged. These busted lines, if even one safety system fails, could leak massive amounts of oil into the Pacific Ocean from Long Beach to the city of Torrance. Fires would also likely erupt throughout LA’s South Bay, where dozens of refineries and thousands of pipelines sprawl across the toxic concrete landscape.

This isn’t some brilliantly farfetched Philip K. Dick science fiction of dystopian Los Angeles. All of this already happens more than you might think. LA’s oil industry has a long history of explosions and leaks, and earthquake activity only increases these risks further.

Luckily, there’s a short moral to this story. The sooner we kick our oil and gas habit the safer we’ll all be when the Big One inevitably arrives.