The twentieth century is the century of socialism. Understanding its successes and failures around the world are crucial to understanding the history of that recent century and the potential future of the current one. A recent addition to the multitude of historic reflections published on this subject lends a uniquely US perspective. The author, Paul LeBlanc, is a long-time socialist whose tendency leans toward Trotskyism. This latter fact is one that seems to matter mostly to other leftists and certainly does not detract from the history LeBlanc tells.

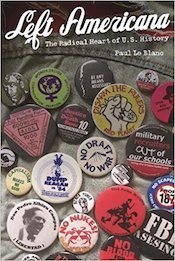

His book, titled Left Americana: The Radical Heart of US History, is a collection of historical reflections established in a context that combines Marxism and United States history. Its subjects range from Chicago’s Haymarket martyrs to the nuances of the US Trotskyist movement; from a discussion of CLR James’s approach to Marxism and meaning in the world to a survey of radical and conservative movements in the 1950s and 1960s. Furthermore, he provides a unique, albeit brief, biography of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and an examination of Brookwood Labor College—a not so well known institute of labor organizing in Katonah, New York that instructed dozens of labor organizers in the 1920s and 1930s. The critical history LeBlanc provides goes beyond dates and details, delving into the meaning of the individuals and events discussed for today’s readers.

LeBlanc himself is a professor of history and a socialist organizer. His personal political biography extends over sixty years. After doing some political work in the milieu that would become known as the New Left, LeBlanc found the Trotskyist organization called the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) to be the best vehicle for understanding and organizing against the US war in Vietnam and for Black liberation. That organization, like so many leftist groups in the United States, was constantly in debate over its interpretation of Marxism and after numerous splits, expulsions and power struggles, looks nothing like it did during LeBlanc’s participation. His discussion of the political debates and accompanying power struggles within the SWP and the broader Trotskyist movement in the United States pepper several of the essays in this book. To the reader unfamiliar with the ins and outs of sectarian leftism (or those who find sectarianism to be counterproductive), these nuances will seem to be beside the point. To those interested in the particular histories of the US Left, LeBlanc’s insights could be quite useful.

A common response to the why the US has never had a broad-based and popular socialist movement capable of actually gaining power on a national scale is that socialism is considered

a foreign philosophy by many US residents. LeBlanc’s text  challenges this specific claim, pointing out the role played by socialists in the labor movement, the civil rights movement and the US antiwar movement. The historical truth, however, is that, with the exception of a few Congressional and (arguably) a couple presidential campaigns, the primary influence of the socialists in the United States has been mostly behind the scenes. In other words, socialists worked as organizers and foot soldiers in the aforementioned movements; and as educators both in the US educational system and in the streets. This fact is even truer since the anti-communist crusades that followed World War Two and effectively purged all socialists and communists from most labor unions.

challenges this specific claim, pointing out the role played by socialists in the labor movement, the civil rights movement and the US antiwar movement. The historical truth, however, is that, with the exception of a few Congressional and (arguably) a couple presidential campaigns, the primary influence of the socialists in the United States has been mostly behind the scenes. In other words, socialists worked as organizers and foot soldiers in the aforementioned movements; and as educators both in the US educational system and in the streets. This fact is even truer since the anti-communist crusades that followed World War Two and effectively purged all socialists and communists from most labor unions.

LeBlanc closes his text with an essay written about the Occupy movement of 2011. Citing its historical antecedents and the potential for a revolutionary movement it seemed to hold, he calls for an injection of the ideas of revolutionary socialism into the promise Occupy represented. As anyone who participated in the Occupy movement knows, the multitude of issues and political philosophies present in the parks and streets where Occupy took place was simultaneously a blessing and a curse. The need for an all-encompassing analysis was obvious to those who had previous experience in organizing, but that analysis was never quite shaped. This was due in part to the brevity of the movement—a brevity enforced by the crackdown by police and other law enforcement—and the movement’s intentionally inclusive assembly model. It seemed that some type of radical leftist analysis was developing as other analyses simply failed to provide a way forward or proved to be mere facades for the Democratic Party. Although his perception is somewhat more optimistic than mine, LeBlanc’s conclusion that the only way the people of the United States can prevent what portends to be a very ugly future for all but the rich is through revolutionary socialism is something I can certainly agree with.