[After her talk before the Congress of Religious Philosophies in San Francisco (1915)] ‘Atheism is a rather delicate subject to handle under such circumstances,’ wrote Emma Goldman, ‘but somehow I managed to pull through…I was followed by a rabbi, who began by saying that “in spite of all Miss Goldman has said against religion, she is the most religious person I know.” ‘

— Emma Goldman, Living My Life

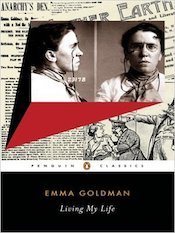

Knowing very little about the anarchist Emma Goldman, reading her autobiography, Living My Life, I was pleasantly surprised to find it is not at all a turgid read. It has incredibly enriched my knowledge of American history, and left me absolutely astonished that such a story of a woman’s unparalleled courage, even jaunty courage at times, packed with explosive dangerous confrontations with police, vigilantes, judges and “patriots,” as she calls the group that could carry the same name today, and filled with romance as well – has never to my knowledge been made into a major Motion picture. That hatred and fear of anarchy would prevent such an obvious blockbuster about a woman of ideals and passion, suggests the point about our country that the anarchists made; freedom in America is an illusion and the powerful interlocking interests working to the disadvantage of common humanity must be challenged repeatedly and tirelessly.

Perhaps what startled me most (so far) was Emma’s published defense of the man who assassinated President McKinley at the Buffalo Exposition in September 1901 during a time when newspapers and “patriots” were calling unanimously for his blood, and even her fellow radicals had backed off: “Leon Czolgosz and other men of his type,” she wrote, “far from being depraved creatures of low instincts are in reality supersensitive beings unable to bear up under too great social stress. They are driven to some violent expression, even at the sacrifice of their own lives, because they cannot supinely witness the misery and suffering of their fellows. The blame for such acts must be laid at the door of those who are responsible for the injustice and inhumanity which dominate the world.” This she wrote at a time when the press was calling for death to all anarchists and in particular, to Emma Goldman, who had nothing to do with the act.

Her defense of the man Czolgosz is a statement – it could be called self-serving if one insisted on disliking Goldman – about herself and about men like Alexander Berkman, her lover who served a 22 year sentence in prison in Pittsburgh for the attempted assassination of the virulently anti-labor industrialist Mr. Frick. These men, she’s saying, – we anarchists – are not brutes, monsters, unnaturally violent creatures. We are the opposite; we are too sensitive for successful assimilation to this brutalizing condition to which we are expected to adapt as if there were no choice.

Her statement is as clear a defense of the human soul as any I have ever read. It caused me to conclude that for Emma at least, that was the point of anarchism: to defend that aspect of the human being that is incorruptible, that provides the base for moral thinking which does not necessarily conform with socially enforced mores, that makes it possible both for the human being to endure suffering and to feel compassion for the suffering of others. It is a defense of interior knowing, thus completely based in individuals who insist their own inherent  knowing is right, or righteous. This should be seen as the quite remarkable attitude it is, profoundly admirable. I think of the sensitive ones now, the ones who cannot adapt, the ones who are losers, who become mentally ill, or drug addicted, or just failed in one of the many ways we can fail. We have learned so well the lesson of survival of the fittest, the lesson to not be “so sensitive” that most of us are successfully hardened to the very realities, cruelties and barbarisms that are business as usual for the system that serves corporate capitalism. How demoralized we’ve become in just over a century, that we now can afford to sacrifice the most sensitive souls, the ones who just don’t have what it takes, the ones who, like Goldman and her comrades, would have been thrown into despair, and from despair and heartbreak into courageous activism. This hardening of our hearts makes counter culture impossible; we cannot resist, we cannot be the outsiders that we would have to be were we to “smash the old idols of ourselves” (D.H. Lawrence) and dedicate ourselves to building instead a world safe for human souls.

knowing is right, or righteous. This should be seen as the quite remarkable attitude it is, profoundly admirable. I think of the sensitive ones now, the ones who cannot adapt, the ones who are losers, who become mentally ill, or drug addicted, or just failed in one of the many ways we can fail. We have learned so well the lesson of survival of the fittest, the lesson to not be “so sensitive” that most of us are successfully hardened to the very realities, cruelties and barbarisms that are business as usual for the system that serves corporate capitalism. How demoralized we’ve become in just over a century, that we now can afford to sacrifice the most sensitive souls, the ones who just don’t have what it takes, the ones who, like Goldman and her comrades, would have been thrown into despair, and from despair and heartbreak into courageous activism. This hardening of our hearts makes counter culture impossible; we cannot resist, we cannot be the outsiders that we would have to be were we to “smash the old idols of ourselves” (D.H. Lawrence) and dedicate ourselves to building instead a world safe for human souls.

We exist now in a context in which it is possible and even usual to behave as if we had no interior being; to exist without a soul. President Trump, whom artist Enrique Martinez Celaya recently referred to as a “fabrication” of a human being, horrifyingly represents what we have become. Is it possible anymore, when introspection is so universally avoided, to acknowledge the powerful longing for a world that would provide each one a home for his/her complete being – beginning with that too often suppressed desire for one’s own individual creative expression? Could it be possible that “being one’s unique self” – that popular vapid cliché – could be known again for what it is – a radically transformative, transgressive act that places one outside the dominant culture, as “alien” as were Emma and the other anarchists and radicals of her day? Could “being one’s unique self” be understood as the basis for coming together in real need of each other, not only to resist the oppressor or to build utopian off-the-grid community, but to be valued for one’s very struggle to be the full, distinct, dignified self that one is? Could there be community based not upon our assuming we want the same things, but upon our willingness to confess to each other our secret, unacceptable selves, our struggle to be human? Could there be conscious community building (or movement building as lefties always say) that does not take our humanity as a given fact but as a process of becoming that must be carefully tended, nurtured, encouraged and expected of each of us?

Her words spoke powerfully to people who possessed enough of a living culture they’d brought with them from the old country, based in alive souls, that they could easily understand the need to oppose industrial imperial corporate domination, the aim of which is the destruction of a human-supportive environment. Her words were automatically repulsive to the fat and increasingly satisfied liberal middle class that could not follow its ideals through to their revolutionary implications, in whose clutches words like “freedom” would come to mean freedom to choose consumer brands and vacation locations, not to become their full counter-cultural (and perhaps disobedient) selves.

Now, with few willing to identify as or with the oppressed, or as common ordinary humanity, we have no left left; “Your revolution is over, Lebowski.” The reality of oppression has become invisible to the vast suburban-rural dwelling middle class, because we allow masks, human facsimiles, internet and screen versions of our embodied selves, to go unchallenged, held together by mutual agreement never to confess our true inner condition. That is, we are held together by our unspoken agreement to suppress and deny our souls. If we were to recognize this oppression of the reality of the soul, we might re-enter the reality of the struggle against the dehumanizing corporate context. Such recognition is ruled out by the pervasive religiophobia dominating the secular left, making genuine moral vision unattainable on the left.

The banality and nihilism pervading the world ruled by corporate capitalism is the consequence of soul murder (animacide); death to the soul is necessary for capitalism to prevail. Reading Goldman, I am seeing anarchism as the political voice of genuine counter culture based, in turn, in the true inherent individualism of the soul that produces out of its universal matrix (the world soul or anima mundi) legions of individuals, as nature produces the marvelous multitude of leaves of grass. Only individuals convinced of their own truth without deference to outer authority can muster the energy and passion necessary to emerge from the enslavement to banality, junk culture, mutually reassuring emptiness.

If I were in dialogue with Emma, my accent would be on the inherent basis for anarchism rather than to the anti-government radicalism for which there is no spirit in liberal America. My question is first not what you are outraged about, but what do you want? If each person takes up his or her art, the work of one’s particular genius, the path taken would be the destiny expressed or defined by the individual, not by the society or by corporate capitalist consumer culture. Though Emma Goldman needed no help identifying her destiny, and built her entire life’s work on the assumption that she had one and that it was a sufficient basis for action on its behalf, today a spiritual, “idealistic” basis must be intentionally sought by men and women in defiance of religiophobic secularism.

Traditional religious practices acknowledged the difficulty of staying in the state of mind that made it possible to see from the perspective of the eternal, the relatedness of all things. Today, to remain rooted in that perspective is to be the heretic, outsider, artist, maverick – no less so than were Emma Goldman and her comrades in late 19th, early 20th century America. To remain consciously grounded in alternate reality, the [counter]culture in which my nature is at home, I find I have to withdraw into myself, into my reflective, self-dialogic state many times in a single day. I’m no yogi; Staying conscious is something I fail at much more than I succeed! The practice of writing allows me this perspective, but I cannot write 12 hours a day. We have to step out into the world of action, of dailyness, of our projects, of our family and community, and our making a living, all of which in the absence of unifying religion or idealism, tear away at the fragile poetic, imaginative reality. Once taking our attention off it, the beach is wiped clean of foot prints by the tide, the breadcrumbs are snatched up by birds, and the path is gone: to return, each time, to that condition is like standing before a blank page or a blank canvas; one has to confront one’s fear that nothing will come, that the wall between myself and the creative spirit is the end, there is nothing behind it. Each time one steps through that opaque wall that believably convinces us this conventional reality is all there is, it is a feat of magic, a revolution, a redemption.

The work of building a world based in anarchic principles is a parallel task of faith and imagination, of acting without help or support from the larger context. But if it’s understood that our native longing for very human-friendly things, for love, family, good work, connectedness with the earth and its beings, for beauty and for dance, is the motivation, and the longed-for our goal, we might keep each other at the Sisyphean task. How else can we keep love real in the world?