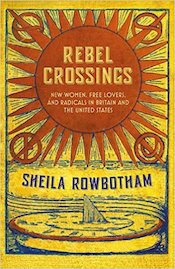

Rebel Crossings: New Women, Free Lovers and Radicalism in Britain and the United States.

By Sheila Rowbotham.

New York: Verso, 486pp, $34.95.

The connection between the British and American Left over the course of something like a century and a half, up to the present, remains a subject too little explored. There are good reasons: much of the story has been anecdotal, involving the passage back and forth of individual radicals and their influences, political, cultural and economic. Take the case of E.P. Thompson, one of the greatest of English language historians in the twentieth century: he had an American mother, and a host of disciples across the ocean who in effect rewrote US labor history. Or his black history counterpart C.L.R. James, another greatest, an adopted Britisher (born in Trinidad) who also became an adopted American, notwithstanding his expulsion in the McCarthy Era. By no coincidence, Rebel Crossings author Sheila Rowbotham happens to be a former student of Thompson, your reviewer a disciple and biographer of James: a small double-slice of a large shared radical history.

There’s much, much more, but to understand it best, a visit to the later nineteenth century is in order. Rowbotham charted in earlier works how the cultural, notably also sexual radicalism came to British society of the Victorian Age, and helped set the tone for women’s emancipation (not to mention the defense of homosexuality) in the generations to follow. More than in the US of the time, the sensibility of such intellectuals overlapped with the political Left, so much so that novelist-poet-designer William Morris led a wing of the socialist movement. By 1900, the influence of Britishers upon the young Socialist Party of Eugene Debs could be felt, but mainly in limited literary circles. The exceptions are notable and important. Over the following twenty years, Chicago socialist publisher Charles H. Kerr offered works by a handful of British writers, notably the bohemian-gay essayist Edward Carpenter (Rowbotham wrote a notable biography of him) to a popular readership. British and American socialists of a certain type also shared one special, socialistic god: Walt Whitman.

Rebel Crossings approaches this subject of what we might call radical overlap by way of fascinating, free-spirited  individuals, often personally lost in the need to make a living and make a meaningful life for themselves. They are not famous nor are their published writings, prose, poetry and reviews, especially memorable. It was obviously the discovery of personal papers of various kinds, letters and clippings as well as published fiction and non-fiction, that brought the author to these people. If they exert no memorable political effect and would be lost to history without the staggering archival work of Rowbotham, still, they have a lot to tell us.

individuals, often personally lost in the need to make a living and make a meaningful life for themselves. They are not famous nor are their published writings, prose, poetry and reviews, especially memorable. It was obviously the discovery of personal papers of various kinds, letters and clippings as well as published fiction and non-fiction, that brought the author to these people. If they exert no memorable political effect and would be lost to history without the staggering archival work of Rowbotham, still, they have a lot to tell us.

What they have to say is discovered in the details, irreducible to any simple lesson. More than anything, they deal most especially in the lives of women seeking a dimension of freedom unlikely anywhere at the time—and paying the price.

Helena Born, her first case, offers a splendid example of the wandering radical. Born in Devonshire in 1860, she grows up a free thinker with wide interests, a supporter of women’s causes, and a devotee of Walt Whitman. Miriam Daniell, her intimate friend, shared with her a vast fondness for Edward Carpenter, himself a Whitman devotee, sympathetic for causes like the local Bristol Socialist Society. Miriam apparently took a lover, socialist Robert Allan Nicoll, resulting in a scandalous divorce proceedings, an event less notable than her engagement with the emerging “new” labor movement of solidarity across craft lines and beyond, embraced by young socialists in ways suggestive of bohemians’ enthusiasm for Wobblies in the US a decade or two later.

Then they began to feel stuck and set off with excess enthusiasm, as it turned out, for a new life across the Atlantic. Boston drew them because of the aura of Thoreau, a half century earlier, but Boston of 1890 was not exactly a beehive of free thought or radicalism. It did have a literary class that, very shortly before, fell in love with the Western Massachusetts utopian novelist, Edward Bellamy or, rather, with his best-selling novel, Looking Backward. The Boston “Nationalist” club, hoping to translate this novel into reality, was one of the strongest anywhere, although it did not last long. Here also was Benjamin Tucker, the anarchist philosopher notable mainly for his embrace of women’s rights including sexual ones, and for his publication of Liberty, a journal of free spirits and open pages. Through these circles, the three met other radical emigres and would-be litterateurs (also, real and would-be free lovers). Soon disappointed with an impoverished life in Cambridge, Helen and Miriam succumbed like so many others, past and future, to the siren song of California. There, Miriam died young, leaving her child to be raised by her friend. The adventures continue, both West and back East, all the way to Britain.

Her friend Helen sent Miriam’s poems to The Conservator. There hangs a tale. Edited, published, even typeset by Horace Traubel–Walt Whitman’s boyish companion in the Great Gray Poet’s last years–The Conservator, a socialistic literary weekly, stood at the center of the Walt Whitman Fellowship. Annually, leading lights of offbeat American letters and radical politics, acerbic newspaperman Don Marquis of “Archie and Mehitabel” fame to Gene Debs himself, gathered annually to remember their late savant, or wrote stirring messages for publication in The Conservator. In an age before Whitman’s universal fame, the Fellowship and Traubel’s publication of Whitman’s late life conversations (running several lengthy volumes) together were the flag-holders for Walt and perhaps, more cryptically, homosexual legitimation.

We also see the intermingled lives of William Bailie, Gertrude Dix, and along with them, the scholar Helen Tufts, in some sense the inspiration for the whole study through a “Biographical Introduction” to a 1902 volume on Whitman. These people, too, are anarchists of a sort, seeking but not finding an escape from commercial society. Dix, also from Bristol, was an enthusiast for the then-shocking works of sexual free-thinking Havelock Ellis but also for socialistic propaganda bringing her close to working class lives. An aspiring novelist, she married Bailie and also set out for California, finding a destiny amidst curious colonies with limited spans. Artistic offshoots of these experiments in living could still attach themselves to Isadora Duncan’s daring modern dance, from Mill Valley to San Francisco, as late as 1920. Later on, Helen herself formed an opposition to the red-baiting in the Daughters of the Revolution (DAR), rousing aristocratic condemnation of her in the press. In various ways, they went on trying, as best they could, to create a freer society.

There is much, much more in Rebel Crossings. The detail of the lives of Rowbotham’s subjects, their literary efforts, their urgent efforts to work out their visions of individual freedom but also a political vision, is sometimes overwhelming at first glance. And then, at closer examination, the cause for such detailing becomes clear. Rowbotham has entered their lives almost as if they were her contemporaries, the political and cultural dreamers of the 1960s-70s, generations later still sure something far better could be worked out, as much personally as politically.

New Age radicals who imbibed LSD (the reviewer admits to it, without admitting he liked the experience very much) can understand the quest for what Whitman devotees were wont to call “Cosmic Consciousness.” The curious cults around this quest, “New Thought,” Theosophy, mind-travel (socialist women of Iowa, shortly after 1900, insisted they communicated this way, although perhaps the coming prevalence of telephones ended the effort), and the pursuit of mystical Eastern knowledge took shape and changed shape repeatedly. Not to mention health-food, the efforts on both coasts to grow and sell what we would call organic produce and offer theories about it, too. Parts of California, appealing to just these kinds of Yankees moving West from New England, offered what might be considered a last major phase of American utopianism before the 1960s.

Sexual activity hovered always somewhere near the surface, naturally more discussed than practiced, finding its way among the casually married but notably also unmarried, older women of obviously strong character with younger men–sometimes with the practice of “karezza” or non-ejaculation. Passionate trysts against picturesque Western backgrounds seem about right for a reading class of Americans fascinated with their own brand of exotica. Literary careers found takers in popular magazines that had wide readerships and paid writers something if rarely enough to live on.

It was all too much for “Sunrise,” the daughter carried out West early in the story. She eloped with a railroad hand and was apparently never seen again. This may remind us of how uncomfortable young people may have felt around middle aged bohemians with curious ideas, like the beach nudists of the 1960s-80s whose kids asked them to please put their clothes back on. The survivors of the earlier day, meanwhile, grew old still campaigning for the legalization of birth control. On the last page, Helen’s daughter becomes a professor and a civil rights advocate of the 1950s. A suitable conclusion, surely.

Rowbotham writes about the 1890s Boston socialist, Martha Moore Avery, that she “was notorious for expounding Marx’s theories as if they were an esoteric form of higher knowledge.” (p.183) This could be taken as a satirical comment on the “romantic individualism” of the people in Rebel Crossings. A sectarian Marxist of the same time wrote that, for all the working class cared, Mary Baker Eddy–whose Christian Science had a lot in common with contemporary mysticism–could be buried in Boston Baked Beans. But how sure are we now, in the twenty first century, that Marxist theories were not interpreted as esoteric knowledge by minds more far more rigorous than that of the forgotten Martha More Avery? At the end of the Introduction, the author says that our failure to break through to a better society remains somehow baffling and yet, “the combination of liberty, love and solidarity” (p.7) of her characters represent something we need today. Well done, Sheila Rowbotham.