The numbers game is intriguing. There were 187,000 prisoners in Turkey’s jails back in March. Since the failed coup in mid July, the cops have picked up, imprisoned or “detained” for interrogation at least 23,000 soldiers and civilians, judges, journalists, teachers and civil servants. The figure may be as high as 32,000, even 35,000.

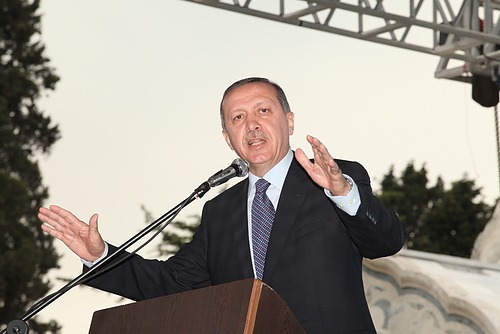

And now, out of the blue, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government empties from its jails 38,000 inmates who have been in clink since before 1 July; in other words, criminals who could not have participated in the attempt to overthrow Erdogan 14 days later.

So 38,000 convicts walk out of their cells to make way for the Sultan’s new batch of prisoners. The government insisted this was no amnesty; which, of course, it was, since there appears to be no system of ensuring that newly-released inmates will not repeat their offences. Incredibly, the release decree was described as part of a “penal reform” across the country’s 364 jails.

It’s also an interesting reflection not only on the ease with which Turkey can free its prison population – albeit that inmates guilty of serious crime such as murder or rape will not benefit – but also of how one major political crisis can so swiftly overwhelm the country’s security system.

When the Turkish army itself staged a coup in 1980, the prison capacity had to be raised from 55,000 to 80,000 to accommodate a vast selection of new “security” detainees. These mostly male prisoners, from the far left and far right in Turkey and who participated in what was largely regarded as an incipient civil war, languished for many years, often without trial. There is no reason to suppose that the next lot of inmates will fare much better for their supposedly Gulenist crimes.

Already made infamous by the depiction of corruption and sadism in the movie Midnight Express, Turkey’s jails have a sinister reputation for cruelty that goes back to the Ottoman days. The country’s most famous prisoner, the Kurdistan Workers Party leader Abdullah Ocalan, will presumably continue to endure his eight-and-a-half-year incarceration on Imrali island in the Sea of Marmara in solitary confinement.

While his followers have often filled Turkey’s prisons in the south-east of the country – especially in Diyarbakir – the ferocious battles in which they have been engaged by the Turkish army have been so bloody that they appear to have produced more dead bodies than prisoners. More than 21,000 Kurds are believed to have been killed between 1984 and 2012, and another 2,000 between July and September last year.

Oddly, the same set of decrees that have freed 38,000 prisoners included the dismissal of 2,360 more police, at least 100 more officers and soldiers and about 190 civil servants. We can presumably take it for granted – given their new batch of inmates – that prison wardens will not be included in future dismissals.