With each passing year, Iranian film and cinema appears to be going from strength to strength, with producers, directors and screenwriters alike offering better and better content to their audiences and in so doing delving deeper and deeper into germane topics once deemed verboten for open consumption on the screen. This industry has also fine tuned over the past thirty-seven years a uniquely Iranian form of film noir that is capable of tackling a wide range of topics simultaneously while offering multifaceted commentary (whether by symbolism and metaphor or even openly without such devices) on a range of issues and questions, such as the class conflict endemic during the Pahlavi era’s modernization efforts where modernism and europeanity were synonymous together with a toxic and abusive elitism; while, in contrast, traditionalism and cultural authenticity stood at the opposite pole. This specific question was also one of the main themes covered in the late Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s (d. 1969) momentous essay entitled Westoxication/Occidentosis (gharbzadegi): an essay that literally set the tone for a whole generation of post-1953 activists leading up to the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

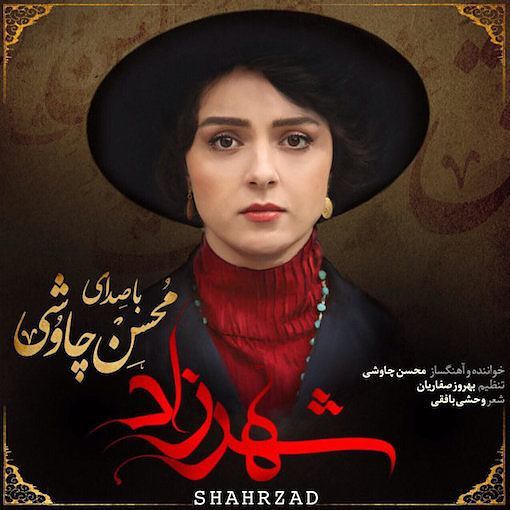

With that said, I have lately been watching the ongoing Iranian series ‘Shahrzad’ which so far has me spellbound because it resonates with so much that Al-e Ahmad was talking about. First, though, note the name connected to the title of the story here which is a direct reference to the chief female protagonist of the 1001 Arabian Nights which this series — in veiled terms as well as openly — often refers to. Our own main character in this story (played by Taraneh Alidousti) is also named Shahrzad, through whose eyes and experience an entire tumultuous narrative of love and betrayal, marriage and divorce, birth and death, crime and punishment, justice and injustice, and especially ‘class struggle’ unfold. The setting is 1950s Iran during the immediate period of the consolidation of the Pahlavi dictatorship following the overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh and his democratic nationalist government. The series is directed by Hasan Fathi with its screenplay written by both Hasan Fathi and Naghmeh Samini. Other stars include Shahab Hosseini (playing the character “Qobad”), Ali Nassirian (“Bozorg Agha”), Mostafa Zamani (“Farhad”) and Parinaz Izadyar (“Shirin”). Twenty-six episodes have aired as of the week ending on 22 April 2016 and more are on the way.

The Plot

The plot follows the storyline of Shahrzad who is a medical student at the University of Tehran. Her fiancé is Farhad who is a student of Persian literature as well as being a leftwing nationalist journalist and activist who works for a newspaper with openly pro-Mossadegh sympathies. Together they frequent Tehran’s famous Cafe Naderi, which during the 1950s served as a meeting hub for nationalist and leftwing intellectuals and university students opposed to the Pahlavi regime. The families of Shahrzad and Farhad are close, with the fathers of the two being best friends. Both fathers of Shahrzad and Farhad are also intimate cronies (i.e. Iranian goodfellas) to a leading Tehran mafia figure known as Bozorg Agha (Mister Big), the chief patriarchal figure of the Divan-Salar (crime) family, to whom they owe their livelihoods.

On the day of the August 1953 coup d’etat (28 Mordad 1332) Farhad is arrested by military authorities following the storming of the offices of his newspaper by hired thugs associated with the pro-royalist coup plotters (presumably of the CIA connected Rashidian brothers) when one of these hired thugs accidentally falls off the office balcony and is killed as he is about to attack Farhad. A post-coup military court then sentences Farhad to death by firing-squad but at the last minute he is saved through the intervention of –- and with the implied bribery of officials by — Bozorg Agha and so is released. However, Farhad’s release and rescue from execution comes with a heavy price for his family and his fiancé Shahrzad, as one of the conditions set by Bozorg Agha for intervening to save Farhad’s life is that Shahrzad relinquish her engagement to Farhad and instead become a second (simultaneous) wife to his nephew and son-in-law Qobad whose own wife, daughter and only child to Bozorg Agha (i.e. Shirin) is barren and incapable of producing a heir for the Divan-Salar (crime) family dynasty. Shahrzad’s father, Jamshid, although compelled by Bozorg Agha, gratuitously agrees to the marriage to shore up his own social position and financial security; but Farhad and Shahrzad soon attempt to elope, only to be caught and separated by Bozorg Agha’s men half way to Shiraz with Shahrzad brought back to Tehran by force while Farhad is beaten half to death and within an inch of his life by Bozorg Agha’s men and left where he is. Meanwhile authorities of the military junta goverment of Fazlullah Zahedi have ordered the shut down of the pro-Mossadegh press.

The Themes of Shahrzad

Without a doubt, Shahrzad is one of the best among Iranian epic drama series made so far simply because of the range of themes and topics it covers. It is a veritable Iranian Godfather plus love story plus historical docudrama plus serious social commentary plus constant reflection on what the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo dubbed ‘The Tragic Sense of Life’ — but contextualized in a consummately traditional Iranian sort of way — all rolled into one. Besides the social and political questions touched upon, replete are also theological and metaphysical speculations on God and the devil, free will and fate, the nature of good and evil, and the capacity as well as limitations of the human heart for suffering.

Iranian style melodrama abounds, but (just like Da’i Jan Napelon/‘My Dear Uncle Napoleon’ of Iraj Pezeshkzad) even the melodrama offers poignant commentary on important facets of the social psychology of Iranian society and the individual within it. The nature of family and individual; friendship and enmity; loyalty, betrayal and sacrifice; sexism, misogyny and gender inequality; love, jealousy and its vicissitudes; guilt and innocence; pride and prejudice; tradition versus modernity; war and peace; anger and equanimity; crime and punishment; independence versus duty; pathology and sanity; are all beautifully explored here one by one. Episode 11 even deals with the subject of the occult whose theme then symbolically looms around one specific character in subsequent episodes (i.e. Shirin) and her murderous jealousy of the ‘other woman’ (i.e. Shahrzad) whom Qobad has legally wed (and on her own father’s specific orders, no less). Shirin’s jealousy and hatred, together with the arrogance of her social rank and privileges, trigger in her a total psychological meltdown which elicit nocturnal delusions and even somnambulism (i.e. “sleep walking”) — and in one scene, even murder! Great lines of poetry from the Persian literary classics abound, as do some of the classics of modern Iranian poetry as well (i.e. Nima Yushij, Parvin Etesami, etc), wherein tradition and modernity and their tensions are juxtaposed within the greater constellation of the story’s depiction of the times. Moreover, the shadow of Shakespeare’s ‘Othello’ especially hangs wide over the story here.

Corruption, Westoxication and Classism of Iranian elites during the Pahlavi era

The series throws a massive limelight on the corruptions of the secular Iranian upper classes during the 1950s of the Pahlavi era in the immediate post-Mossadegh period. It especially underscores the abuses, callousness, cruelty and, above all, the complete absurdities of patriarchy and its power structures under this specific parasitic Iranian social class of the time (neither aristocrat nor bourgeois; neither traditional nor modern; but something in between, wherein this class’ pretensions to Europeanness and europeanity instead betrays it according to the worst, most tragic caricatures of oriental despotism): a topic which is quite risqué and avant garde for the Iranian screen to be broaching in the probing manner it is being dealt with here.

Class conflict and the wanton exploitation and disposability of the traditional Iranian working classes in the totally feudalistic and pathological views of the upper classes of the era is graphically depicted, not to mention how such warped power relationships and dynamics in the wider Iranian society project and play themselves out inside family and social networks alike, especially in courting and marriage. Poignant contrasts between this so-called modernized and europeanized elite and the lower classes they mercilessly exploit and prey upon is highlighted in the choice of attire, artwork and architecture associated with this elite with the near complete absence of anything authentically traditional or Iranian among them. For example, the Divan-Salar family totally surrounds itself with European Baroque style architecture and artwork while exclusively donning the attire of the European upper classes of the era. They also consume large amounts of expensive alcohol wherein the amoral classist decadence of their behaviour is writ large. In contrast, the lower classes are depicted as more traditional, more culturally bound and earthy, more humble and less hypocritical, sincere in their religious convictions, while authentically guided by an ethical compass and empathy for others, and, above all, a sense of social justice that is completely absent in the upper class ‘europeanized’ Iranians with their cultural nihilism and westoxicated self-orientalization.

While all this may be dramatization to some degree, it also accurately reflects to a large extent the social mores of the Iranian ruling classes of the Pahlavi era: social mores which are persistent thirty-seven years later and still in evidence amongst this westoxicated/occidentalized sub-culture either among the Iranian diaspora in Tehrangeles or in the wealthy suburbs of north Tehran. Only the marriage ceremony of Shahrzad to Qobad, as well as the big black onyx ring sitting on Bozorg Agha’s right-hand ring finger, exhibit any semblance of the larger Iranian Shi’i culture present with the Divan-Salar family; everything else with them being either conspicuously un-Iranian or a caricatured inversion of Iranianity; and this is quite an apropos feature of the story to underscore regarding the socio-cultural pathologies of this predatorial Pahlavi era ruling class whose dynamics the series has so sharply focused on.

Simultaneously, the totally self-serving and unchecked power and corruption of the military officer class –- with their nouveau riche business partners and patrons — who subsequently became quite wealthy as a result of the 1953 anti-Mossadegh coup (together with their criminal lawlessness, sense of entitlement and unaccountability) is portrayed well here. That said, this is largely a story about the Iranian cosa nostra and uber-wealthy families of 1950s Pahlavi Iran with their assorted dependencies and beneficiaries; all being a reflection of the inherently venal, unjust and corrupt nature of the Pahlavi regime itself who literally behaved like a mafia. Such figures and upper class families formed much of the upper crust structures of that society, acting like little shahs in their own right, lording over their mini-realms greedily and with iron fists; where everyone other than these corrupt and decadent westoxicated upper classes themselves were completely and thoroughly (without any sense of remorse or shame) disposable. Note here Shirin’s nocturnal, somnambulistic murder of her long-time, household servant Marmar and the manner of Marmar’s hasty, hush-hush burial at the back of their mansion’s garden on Bozorg Agha’s specific orders in episode twenty-two.

Appreciation

All in all, Shahrzad is a tour de force masterpiece that shows Iranian storytelling at its best: Iranian storytelling reminiscent of its genre in classical Persian literature but in a (post)modern context; storytelling which has now seriously come into its own, intelligently and with great sensitivity covering lots of ground and topics in the process. The acting and character developments of Shahrzad are superb; the direction and screenplay, among the best Iran has yet produced; and all within the parameters of what is deemed acceptable in a conservative religious society like Iran’s. The music is also among the most moving scored for such a series. As such Shahrzad, while still ongoing, definitely deserves a much larger audience.

As a final note, it should be mentioned here as well that the series was officially licensed for broadcast in Iran by the Iranian Ministry of Guidance and Islamic Culture. This last point is cited for the benefit of all those who insist that contemporary Iran is a cultural backwater plagued by censorship and where genuine artistic expression is incapable of emerging organically. ‘Shahrzad’ defies such myopic presumptions and proves such naysayers all wrong, showing high Iranian culture to be alive, well and kicking, and, moreover, that it can literally adapt itself to (and simultaneously inform) any epoch of its choosing be it pre-modern, modern, postmodern and beyond.