The Clintons’ high-profile interest in Haiti dates back almost all the way to their wedding in 1975. Shortly after their honeymoon in Acapulco, Bill and Hillary Clinton received an invitation from David Edwards — a friend and Citibank executive — to accompany him to Haiti.

Edwards’s motivation in getting the Clintons closer to Haiti was neither cultural nor humanitarian. The reason was Citibank’s long-standing financial interests in the country, which now go back over a century.

In 1909, the National City Bank of New York — Citibank — acquired a majority stake in the National Bank of Haiti, an institution that had been under French control and which, since 1880, held the power to issue paper money and to serve as central bank for the Haitian treasury. In 1914, Roger Leslie Farnham — in charge of the Caribbean region at Citibank — pressed Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan for Washington to militarily intervene in Haiti in order to protect U.S. interests. One year later, 19 years of occupation would begin for the country.

It was only the beginning of U.S. meddling in the affairs of its poorer neighbor.

***

In April 2009, the State Department, under the leadership of Hillary Clinton, decided to completely change the nature of U.S. cooperation with Haiti.

Apparently tired with the lack of concrete results of U.S. aid, Hillary decided to align the policies of the State Department with the “smart power” doctrine proposed by the Clinton Foundation. From that moment on, following trends in philanthropy, the solutions of US assistance would be based solely on “evidence.” The idea, according to Cheryl Mills, Clinton’s chief of staff, “was that if we’re putting in the assistance, we need to know what the outcomes are going to be.”

The January 2010 earthquake was the long awaited opportunity to test this new policy.

Mills was no development expert, but her connection to the Clintons ran deep. A graduate of Stanford Law School, Mills had been the unofficial manager of Hillary’s 2008 presidential campaign and Bill’s defense lawyer during his impeachment. Despite having no training or experience in development economics, Rolling Stone reported a few years back, Mills “was determined to figure out a new way of doing things that would be more effective, both for the U.S. and for Haiti.”

The idea was to transform Haiti into a Taiwan of the Caribbean, with maquiladoras, an apparel industry, tourism, and call centers. These would be the niche sectors that would guide the new cooperation framework.

In this plan, the particularities of Haiti itself didn’t matter much.

Yet more than hope, there was certainty that the country would eventually conform to the plans being imposed by the Harvard Business School technocrats. Haiti was to fit within the parameters of capitalist efficiency: “Is this going to be hard? Yes,” Hillary Clinton tearfully told The Miami Herald. “Do I think we can do it? Absolutely, I do.”

The volunteering amateurism of the Clintons was so far gone that Bill publicly declared in a speech in Port-au-Prince that he would make Haiti the first fully Wi-Fi-connected country on the planet.

For the desired policy changes to work within a diplomatic framework, the veneer of “democracy” needed to be maintained. Ergo, Clinton and Mills played a heavy role in Haiti’s contested 2010 elections.

I was present at a December 2010 meeting where the so-called “Core Group” of (initially the U.S., Canada, and France, but Brazil got a spot because of its role in the UN mission) plotted a coup against Haitian President René Préval, until then-Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive unexpectedly showed up. I intervened, citing the 2001 Inter-American Democratic Charter.

Legality and common sense had prevailed. But until when? My hopes were still alive and I did not notice that a common international front had formed; one that would decide Haiti’s electoral path.

After this failed attempt, the Core Group quickly came to realize the absurdity of attempting to depose Préval. Rewriting history, in the following days, several ambassadors, when asked about the topic, would shamelessly lie, denying its existence.

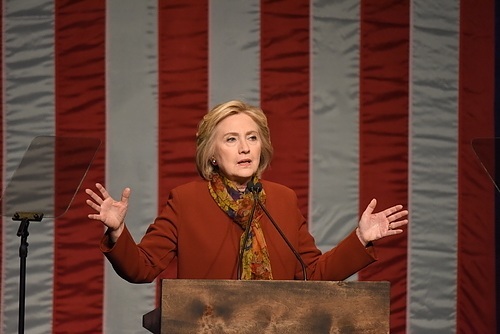

Finally, on Sunday, January 30, 2011, the unavoidable foreign actor in the recurring Haitian political crisis decided to put an end to the dispute. Hillary Clinton had arrived in Port-au-Prince.

The secretary of state had taken care to invite her colleagues, the foreign ministers from the other member-states of the Core Group, to accompany her in a delicate mission to Port-au-Prince. They all declined the gesture, alleging it would be impossible for them to fit the event in their agendas. However, this was not the reason for their refusal. Since the Haitian crisis had been detonated by the United States, even on the night of the election, it was Washington’s responsibility to resolve it.

After talking to several public figures, both Haitian and foreign, the head of the State Department knew that the last meeting before returning to Washington would be decisive. Préval awaited her in his simple office next to the ruins of the National Palace.

Bellerive and Cheryl Mills were also present during the meeting in question – images of which are presented in Raoul Peck’s documentary Fatal Assistance.

Hillary Clinton began the meeting saying she was not interested in who would, or would not go on to the second round. What brought her to Haiti and to Préval was to try to offer him her advice and hear the allegations of his old friend of many battles. What mattered to her was to see that Préval emerged exalted from the crisis. Nothing else. She claimed she had made no commitments to the other actors involved in the crisis or even with the three presidential candidates, only to Préval and his future. He had been a constant and loyal ally. Now he was in a delicate situation, for they were accusing him of acting as a petty dictator, imposing an unknown candidate who had no representation and was manipulable.

For the woman in charge of US diplomacy, it must have been during those moments of uncertainty and difficulties that true friends were found. It was for this reason that Hillary was there, as a friend of Préval and of Haiti, as she always had been.

Towards the end of the meeting, she asked Préval to make a last gesture in favor of harmony and understanding. It was to be a gesture that would lead him, once and for all, to a special place in the pantheon of Haiti’s history and the struggle for democracy in the continent. Préval replied with an emotive, albeit enigmatic smile. It was only him who knew that the crisis had reached its epilogue at that moment.

As she was leaving the house, Hillary invited Bellerive to accompany her. The prime minister asked Préval for authorization to do so and placed himself between the two women inside the armored truck that left in a convoy to the airport. Confident that she had obtained what she wanted, Hillary was concerned now with the result of the second round. Bellerive removed all traces of apprehension when he informed her that Michel Martelly was going to win easily. And so he did.

As she was heading toward the plane, Hillary made a comment to Bellerive about his family relationship with Martelly. He confirmed that they were distant cousins. Since they were both educated individuals and the game was already over, the secretary of state allowed herself to make a joke and asked: “You are relatives, but you don’t sing?” Bellerive replied, humorously: “Neither does he.”

Hillary confessed having heard Martelly sing some songs and could not agree more with Bellerive. Then, smiling, she left Haiti.

This is an extract from Seitenfus’ book, published in Portuguese, Spanish and French. The latter version l’Échec de l’aide intérnationale à Haïti: Dilemmes et égarements, was published in 2015 from the Éditions de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti. Seitenfus is working on publishing the English edition.