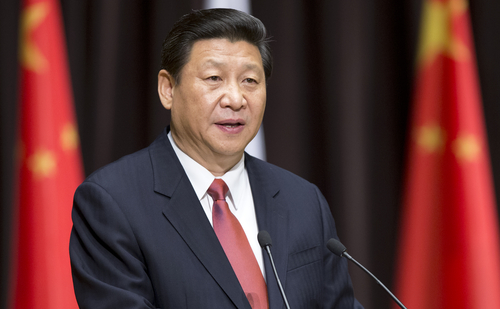

China’s President Xi Jinping has been on a tour of the Middle East, straddling the politics of the region – a stop in Saudi Arabia was balanced by a stop in Iran.

Xi’s most dramatic statements came at the Arab League, where he reaffirmed openly – for the first time in decades – China’s commitment to the Palestinian people.

“China supports the peaceful process in the Middle East,” he said, and it supports “the establishment of a Palestinian state with its capital being eastern Jerusalem”.

This last phrase was the one that rattled the Israelis.

They have refused to budge on East Jerusalem, now a flashpoint of violence. Xi’s remarks advocating for the Palestinians must be heard in that context. It defends the Palestinian view and rejects entirely that of the Israelis.

It is what earned Xi some, but not many, headlines.

No question that Xi’s statement marks a new forthrightness from the Chinese government regarding the Middle East. Since the 1990s, China had been loath to openly declare a position. Commerce drove the agenda, not politics.

China, in the United Nations at least, spoke of the need for peaceful solutions and for multilateralism. These laudable ideas had few takers in an era when the United States drove policy at the end of a bomber.

China’s reticence about the sanctions regime of the 1990s against Iraq and then the war on Iraq in 2003 did not turn into a revolt. Its diplomats made their muffled protests, but then retreated.

When the vote on Libya came before the UN Security Council in 2011, China – with the other BRICS states – decided to abstain. But once the West exceeded the terms of UNSC resolution 1973, China – with Russia – decided to take a more blunt position in the region.

Since 2011, China and Russia have blocked any attempt by the West to gain a UNSC resolution for a war on Syria. China and Russia, as well as the bulk of the Global South, are averse to further regime change operations. Libya was the final straw.

It pushed these countries, which had taken a backseat since the early 1990s, to be more aggressive about their geopolitical alignments. China began to hold military exercises with Russia, including one major naval exercise last summer in the Mediterranean Sea.

It was a significant show of force by these two world powers.

China’s commercial entanglements at the present time prevent any major pivot, however. During this visit, Xi had to shore up China’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

Saudi Arabia is China’s major oil supplier, which means that Xi had to make pleasant noises about Saudi Arabia’s war on Yemen – about which Chinese diplomats, quietly, express their concern.

China’s state oil company – Sinopec – and Saudi Arabia’s oil company – Aramco – signed a major framework agreement for strategic cooperation. Talk of bringing parts of Aramco onto the market did not deter these ties, for they will endure, whether ownership in Aramco is diluted or not.

China reaffirmed its ties with Egypt, on the eve of the fifth anniversary of the Egyptian Revolution, mainly because China is reliant upon the Suez Canal – a major artery for Chinese goods going to Europe.

China’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Egypt are based on the present: China’s economy relies for now upon the fuel and transportation pathways provided by these powers. Xi’s visit to Iran suggests that this reliance is not eternal.

China is also Iran’s largest trade partner and provided a lifeline for Iran during the sanctions era. Both Xi and Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani said that this connection during the sanctions era has built a great deal of trust between Tehran and Beijing.

“China is ready to upgrade the level of bilateral relations with cooperation,” Xi said on Iranian television, now that the sanctions era had ended. Iran proposes to sell more oil to China – to dramatically increase the volume over the next ten years.

This will make China less dependent upon Saudi oil.

Over the past decade, China has been actively building “The New Silk Road” that would run from China’s coastline to Europe, through Central Asia and Iran. Train and road networks have been built across northern Iran to link Afghanistan with Turkey.

Last year, the China Railway Group won a contract to build part of the railway to link Budapest and Belgrade. The New Silk Road has now gone straight from the Shenzhen industrial zone on the South China Sea to the heart of Eastern Europe.

Dependence upon the Suez Canal will not be fundamental to China’s strategic calculations for long.

The emerging China-Iran relationship, in other words, could make China’s current reliance upon Saudi Arabia – for oil – and Egypt – for transportation – less important. Chinese diplomats say privately that the pro-Western orientation of the Gulf Arab states is a hindrance for Chinese planners.

They would like more flexibility in their commercial entanglements. Egypt’s recent entry into Saudi Arabia’s orbit raises these worries. There is little room here for China in case the West uses extra-economic pressure on these countries to cut Beijing out.

It was this fear of Western allies in the South China Sea and the Malacca Strait, such as Singapore, that led China to develop ports in Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu and in Pakistan’s Gwadar.

These ports circumvent the bottlenecks in South-East Asia. The New Silk Road will bypass the Suez Canal.

Xi is well known for his positions on the need for multilateralism in world affairs. The link between Russia and China was strengthened after the 2014 Ukraine crisis, which the Chinese believe was a Western-orchestrated attempt to weaken Russia.

Xi’s commitment to the BRICS bloc is reflective of this attempt to create various poles as a counterweight to Western hegemony. His journey across the Arab world must be seen in this light – as an attempt to shore up support among those who are commercially necessary right now – Saudi Arabia and Egypt – and to indicate support for those who will allow China independent access to fuel and markets – Iran.

Xi’s statement on Palestine does not harken back to China’s historical support for the Palestinian cause. There is little of the echo of 1964, the highest point of Chinese-Palestinian solidarity. That year, China was the first non-Arab state to recognise the PLO.

During Zhou En-Lai’s trip to the region, he said: “We are ready to help the Arab nations to regain Palestine. Whenever you are ready, say the word. You will find us ready. We are willing to give you anything and everything; arms and volunteers.”

China pledged to honour the Arab Office’s boycott of Israel that year, saying that no Israeli ships would be allowed in Chinese waters. A PLO delegation – led by Ahmad Shukeiri – went to Beijing in 1965. Mao declared May 15 to be Palestine Solidarity Day.

At a mass rally, with Shukeiri’s delegation in attendance, Mao connected Israel to Taiwan (Formosa) – as the “bases of imperialism in Asia”.

“You are the front gate of the great continent,” he said. “And we are the rear.” The West would use Israel and Taiwan as springboards into Asia, he affirmed.

“The Arab battle against the West,” Mao said, “is the battle against Israel. So boycott Europe and America, O Arabs!” (al-Anwar, 6 April 1965).

Xi does not speak like that. His manner is milder. It unites the commercial sensibility of Deng Xiaoping with the anti-Western worldview of Mao. The suspicion of Western motives is shared across large sections of Chinese and Iranian leadership.

But China’s quiet days seem over. To have come out openly for Palestine to include the eastern part of Jerusalem is not merely about that patch of land – it is about China’s confidence to say openly what it has for decades only said in private.

A version of this article originally ran in Al Araby.