Last year, I bought my daughter a portable record player for her 16th birthday. She is fascinated with music from the early and mid-60s (the time when I grew up), and I thought listening to records of that music would be a great experience for her. I remembered how much joy I got out of my portable record player as a kid, so I wanted to share that joy with my daughter.

She loves her record player as much as I loved mine. Since I got it for her nearly a year ago, she has grown quite a collection of vinyl from re-issues to original releases that we have found at our local independent and used record stores. So along with an appreciation of vinyl, she has also learned to appreciate the record store (before it becomes another extinct artifact of Late Capitalism). Her collection includes all the Beatles albums (including a few original releases in pristine condition, of which she is mightily proud to own), Simon & Garfunkel, the Beach Boys, Velvet Underground, the Mama & the Papas and Janis Joplin.

After seeing the movie Love & Mercy, my daughter developed a very strong identification with Brian Wilson, and Pet Sounds joined the ranks of her favorite albums of all time. A couple of weeks ago, we pulled her vinyl copy of Pet Sounds off the shelf and listened to it on her record player. The layers of sound are unbelievable. In the film Love & Mercy we see how Brian Wilson worked with studio musicians to create these sounds. He translated his fierce vision into complex layers of sound by working with a whole cadre of musicians who played everything from guitar to cello to bass, drums and saxophone. Hearing the album on vinyl and remembering the scenes in the movie with the studio musicians, the layers of orchestral under-sounds in Pet Sounds became even more mesmerizing.

After Pet Sounds, we pulled a Simon & Garfunkel album off the shelf. I placed the needle on the groove of the record, and we closed our eyes and listened. I hadn’t heard the album since I was a young girl of twelve. The first thing I noticed when I listened a couple of weeks ago was a complexity of sound that I never noticed before. It was especially notable coming directly on the heels of the Beach Boys. I said, “Wait a minute. Do you hear that? This album has the same level of complex sounds as Pet Sounds!”

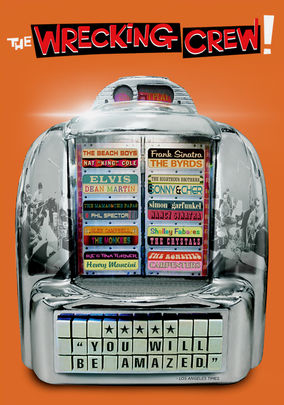

A few days later I watched the documentary The Wrecking Crew on Netflix. I learned of the film after writing about Love & Mercy when a friend mentioned I should watch the documentary about the band that played back-up on Pet Sounds. So I went into the movie thinking it was going to be about the band that played for the Beach Boys. What I didn’t know until watching this documentary is that The Wrecking Crew was the “back-up” band that literally defined a whole generation of music – the very music I grew up with in the 1960s. The reason the sounds on the Simon & Garfunkel album reminded me of Pet Sounds is because it is The Wrecking Crew playing the instruments on both records. It’s the same band, just different vocalists and songs.

The Wrecking Crew consisted of a group of musicians that backed songs from the top of the music charts of the 50s, 60s and 70s. They were responsible for Phil Spector’s groundbreaking “Wall of Sound” featured on such Spector enterprises as The Ronettes and The Crystals. But the Crew didn’t stop with Phil Spector. For nearly three decades, this uncredited band of musicians provided the pop sound that sold records by Elvis Presley, The Mamas & the Papas, the 5th Dimension, Frank Sinatra, Nancy Sinatra, The Byrds, The Carpenters, Sam Cooke, Harry Nillson, Cher, The Monkees, and dozens of other musicians. Check out a sampling of Wrecking Crew songs here.

As I was watching the documentary, and the songs piled up, it was like flipping through the pop radio station dial on my portable radio when I was a kid. My daughter would squeal from the other room as one of her favorite tunes was sampled in the film. “I love that song!” I would chime in with, “I loved that song when I was a kid too!” What I didn’t know is how a specific sound manufactured by the Los Angeles music business was responsible for the soundtrack of my childhood and created by artists whose names I never knew until I watched this film.

Speaking of kids, the movie was made by Denny Tedesco, the son of one of the most hardworking members of the Wrecking Crew – guitarist Tommy Tedesco. The reason I don’t cite the date of the film during its first mention is because assigning a singular date to this movie would be as misleading as giving The Byrds credit for the music behind their hit single “Mr. Tambourine Man,” music which was played by The Wrecking Crew because The Byrds did not actually know how to play instruments when the song was released. The film took nearly two decades to make, and it was only with dedication, sweat, and a lot of scraped-together cash and materials that it ever was released to the public.

Denny Tedesco began making the film in 1996 when his father and other members of the Wrecking Crew were still alive. It is comprised of interview material from Wrecking Crew members, musicians who employed the band, and archival footage and photos. It was an enormously expensive and daunting undertaking. Getting rights to songs that didn’t actually “belong” to the Wrecking Crew proved to be enormously costly, and Tedesco maxed out every credit card and two mortgages on his house before the film was screened at Sundance in 2006. At that time, he hit another wall when he discovered that he needed to come up with an additional $250,000 in royalties to the artists whose songs are sampled in the film (even though the Wrecking Crew was responsible for the music).

Denny raised the money through a Kickstarter campaign and through dedications on the film’s website. Finally, nearly two decades after he began the project, the film was released to the public in March 2015. The sad irony is that many of the original members of The Wrecking Crew didn’t live to see the day when the film dedicated to their work would be recognized by the public – just like their efforts on so many hit songs were never recognized. Tedesco’s final efforts to give voice and recognition to the unsung heroes of mid-20th century pop music were never seen by many members of the band including his own father who died of cancer in 1997. But when we watch this film, we see them and get to know them and appreciate them, and we will never listen to their songs again without hearing the Wrecking Crew. Their hard work stays alive in the movie.

Because Tedesco lives in LA (home ground for the Wrecking Crew, who were Los Angeles studio musicians), he was able to make the film through a lot of industry leftovers. The film is interesting visually for the mere fact that it is piecemealed together from bits and pieces of leftover film stock that he garnered through side jobs. Denny obtained some of the archival footage of the Wrecking Crew roundtable sessions via rolls of porn film which he had to edit and splice to glean the Wrecking Crew material. The film looks and feels like a montage because it literally is a compilation of leftovers, a patchwork of discarded material. Interestingly, the film is a tribute to musicians whose names were largely left by the wayside even though they were responsible for generating millions of dollars for big named artists in a big name business, and the film is made by materials from the film industry that were in turn left by the wayside. Denny Tedesco talks at length about the complexities and costs of putting this film together in a March 2015 article in Moviemaker magazine.

Besides Denny’s dad Tommy, the film features interviews with a broad spectrum of Wrecking Crew members, including Glenn Campbell who graduated from back-up studio musician to star who in turn used the Wrecking Crew on his albums. Most of the Wrecking Crew members didn’t care for pop or rock, but rather they were jazz musicians who used their musical talent to forge a living. They were truly “working musicians,” often working twenty hour days. If they were called upon for a gig, they didn’t dare turn it down or they might lose their place in line, just like other workers bidding for a job.

What is clear in the film is that the Wrecking Crew worked very hard. In listening to some of the artists talk about working with them (e.g. Cher or Nancy Sinatra), it’s almost as though they are talking about a group of workers who did a good job roofing their house. This poses an interesting question. Does busting your balls to make a living playing music (and being the invisible labor behind a huge profit generating business) make you any different than any other laborer? Wrecking Crew members seem to think so. They were happy to do what they loved (play music), and they got paid union wages, though they weren’t given credit on the albums. So are these musicians merely “tools” or was their talent being exploited for profiteers in the music industry? Either way, their music created a sound that defined a significant era in pop music history. I see them as really hard working people who are only just now getting the credit they deserve, paycheck or not.

One of the more interesting members is bassist Carol Kaye who was the only female member of the Wrecking Crew. She clearly held her own and learned to navigate the man’s world of music through sheer strength of will, humor and talent. Carol has no regrets. She talks about her years with the Wrecking Crew like anyone talking about a decent job. She says she was able to take care of her family and make a heck of a lot of money along the way. At one point, she states that she “Made more money than the President.” In 1965, the President made $100,000 per year. I know from growing up in a working class house during the1960s, that anyone making six digits was considered rich by the working class. If you look at the Wrecking Crew as trade workers, their pay was good, but they also made sacrifices for it. They worked long hours and sacrificed time with their kids for time in the studio to earn extra bucks.

The Wrecking Crew had created a niche in the music industry where they became a desired commodity. Their sound was essential for the industry to keep producing Billboard hits. But by1967, pop music was experiencing a paradigm shift. With Monterey Pop (1968) when Americans first saw Jimi Hendrix wail on his guitar and The Who play the fuck out of and then smash their guitars on stage, audiences became hungry for seeing and hearing “the real thing” – musicians who wrote and played their own songs. As this new trend took hold, the Wrecking Crew got pushed to the margins. They became obsolete workers, and Tommy Tedesco spent his final days playing gigs on The Gong Show and waiting for calls from studios that never came.

Interestingly, one of Monterey Pop’s producers was John Phillips of The Mamas & Papas, a band who relied heavily on the Wrecking Crew for their musical accompaniment. One of the most notable scenes in D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary of the festival is when Cass Elliott (Mama Cass) looks stunned, awed and threatened by Janis Joplin’s performance. In retrospect, maybe it wasn’t just Janis’s ferocious performance that threw Elliott for a loop, but perhaps it was also Janis’s backing band Big Brother and the Holding Company, a band that could hold their own as musicians. Cass new the end was nigh, and it was a dawning of a new era.

So many people who appear in the film are now dead. Dick Clark makes many appearances and praises the work of the Wrecking Crew stating over and over again how they defined a musical era and were essential to the sound of pop. It’s great that he says that for this film, but where was he back in the 60s and 70s?

When I was watching the movie, I told my daughter, “Well, the one thing you can say about The Beatles is that they played their own instruments.” But then after a little research, I saw a photo of a disgruntled George Harrison sitting with members of the Wrecking Crew. Then I remembered that my daughter has largely boycotted Capitol Records’ American releases of the Beatles’ albums because they included unnecessary, annoying and distracting orchestral backings because Capitol thought they would be more profitable that way. Well, guess who provided that orchestral backing?

Though some critics have called this film confusing because it is unclear whether Denny was making a movie about The Wrecking Crew or about his father, I don’t see why this is an issue. Why can’t it be both? Certainly watching The Wrecking Crew brought back memories of my childhood. I was born in 1962, one year after Denny was born, and I grew up glued to my AM radio listening to the sounds of the Wrecking Crew (though I didn’t know it at the time). I can hear the sounds of the Wrecking Crew right this very moment playing out of my daughter’s record player in her bedroom. Music is part of our lives, but what this movie shows us is that it is also really hard work for a lot of people who often don’t get recognition.

I was talking to my brother about this movie last night. He is a guitar player and busts his ass round the clock just trying to make it. He said that the thing about musicians is that their workday never ends. They work when they are gigging; they practice when they are home; and they are always scrambling for anything that will help them make it doing what they love even though doing what they love often means working to the bone. Besides being a tribute to the unsung musical heroes of the pop music of the 50s, 60s and 70s, The Wrecking Crew also pays tribute the hardworking musicians who don’t make the Billboard 100 and to yet another obsolete class of workers – studio musicians. Here’s to the uncredited talents who brought joy to my childhood and my daughter’s, and here’s to letting their names be known to the public even as many now are etched on the headstones of their graves.