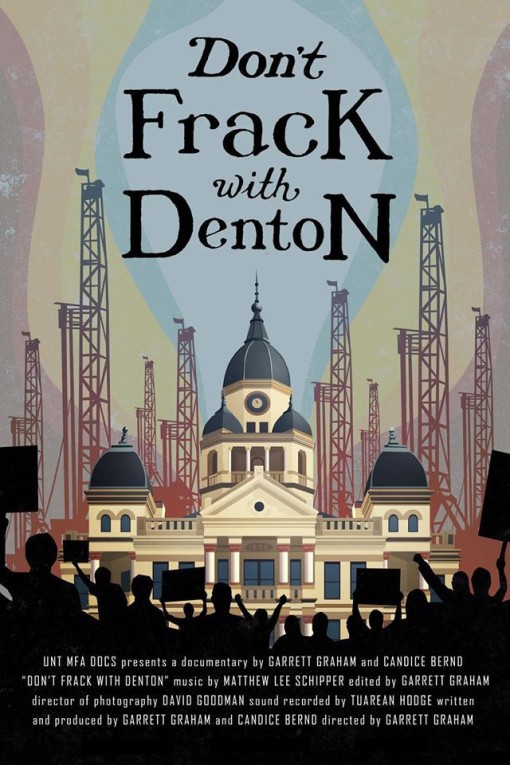

When voters in the city of Denton, Texas, approved a ban on the use of hydraulic fracturing last November, documentary filmmaker Garrett Graham believed he had found the perfect ending to his film about the organized actions taken by a suburban community to stop natural gas drilling.

For months, Graham, a Denton resident, had used his camera to chronicle the meticulous efforts of a group of residents to make their city a haven from the oil and gas drilling practice commonly called fracking. They had jumped through what they believed were all the necessary legal hoops, and after all the votes were tallied, residents erupted with joy upon learning a referendum to ban fracking in Denton had passed.

“They did everything they were supposed to do. They followed the rules,” Graham said in an interview. “They went through all the proper procedures.”

But after their celebrations on the night of Nov. 4, 2014, Denton residents woke up to the reality of Texas politics: the oil and gas industry had filed lawsuits against the measure and state lawmakers promptly announced they would overturn the democratically passed ban in Denton and ensure no other jurisdiction would pursue similar restrictions.

The industry’s immediate pushback forced Graham to come to grips with the fact that the storyline in his documentary, Don’t Frack with Denton, would not be as clear-cut as he imagined on the night the referendum passed. Graham was disappointed with state lawmakers’ response to the vote but was not surprised they vowed to overturn the ban in the forthcoming legislative session.

“Nobody is ever going to blow the whistle and say, ‘Congratulations, you won. You got want you wanted.’ Being an activist, you can’t wait around for celebrations like that because they are so few and far between” Graham said. “It’s ironically very similar to how being a documentary filmmaker feels.”

In documentary filmmaking, the story is never really over. “Time never stops. But we, as documentary filmmakers, have to call cut at some point,” he explained. “At some point, the story has to end, the credits have to roll and people have to go home. But history very rarely ever plays out that way.”

Graham reassessed the direction of the documentary. The film needed to become bigger than the city of Denton. It still would focus on air quality and other health and safety concerns in communities located above the Barnett Shale formation and other natural gas plays. But it also would need to delve into how industries often succeed in grabbing control of governments.

The Texas Legislature kept its promise to industry. It made overturning the Denton fracking ban one of its top priorities of the 2015 legislative session. The bill, House Bill 40, raced through the legislature and was signed into law in May by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. H.B. 40 not only targeted Denton, but placed restrictions on the ability of other cities and local governments that may have wanted to follow Denton’s lead in placing restrictions on the oil and gas industry.

The new law was “basically tantamount to private enterprise using the state capitol as a sock puppet to create situations that are commercially reasonable to their profit incentive, as the language of H.B. describes it,” Graham said.

The state’s pushback against Denton’s fracking ban was demoralizing for many residents. “For some people, this was really devastating news, and for other people, this was old news. It was a really important education for anybody who wants to make change in this society,” Graham said. “When you work really hard to get a ban passed and a bunch of bullies knock it down, it feels bad. And I wouldn’t blame people from being really discouraged.”

State officials were unapologetic in their quest to reverse the vote in Denton, a college town located in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan region. “I’m the expert on oil and gas. The city of Denton is not,” asserted Christi Craddick, a commissioner on the Texas Railroad Commission, the primary state agency that regulates the oil and gas industry. She believed the residents of Denton had no legal right telling the oil and gas industry what it could or could not do.

“When Christi Craddick says she’s the expert and Denton is not, never mind the condescending elitism inherent in that statement; it also fails to understand one of the most fundamental points of human rights and decency, but also one of the fundamental points of the precautionary principle, which is that you don’t need an expert, a scientist, a politician or a bureaucrat to understand the moral and ethical issues at hand,” Graham said. “That’s what’s really important in this story. And that aspect of it has only expanded with H.B. 40.”

If residents come together and decide they do not want an industrial activity in their community because they are concerned about their health and safety, “in a free and just society, that would be the end of the discussion,” he contended.

Nobody deserves to make a call on the issues of health and safety more than the frontline communities that are being impacted, according to Graham. “People ought to have a say in decisions to the degree in which they are affected by them. That is a standard to which most of our democratic institutions horribly fail,” he asserted.

Don’t Frack with Denton is Graham’s second documentary. His first, Blockadia Rising: Voices of the Tar Sands Blockade, put a spotlight on the anti-Keystone XL pipeline movement in East Texas. Graham describes Blockadia Rising as a “video manifesto of the tar sands blockade.” He also collaborated with filmmaker John Fiege on a separate documentary film about environmental activism surrounding the Keystone XL pipeline. That film, Above All Else, premiered at South by Southwest festival in 2014.

With Don’t Frack with Denton, Graham is taking a different approach. He does not want the film to serve as an advertisement for the anti-fracking movement in Denton. While sympathetic to the cause, Graham is aiming to provide viewers with an inside look at the discussions, the debates and the differing opinions that have played out among the residents opposed to fracking in Denton.

He also is not trying to convince viewers on how they should have voted on the fracking ban issue. But Graham’s views on shale gas drilling are clear, and they are diametrically opposed to its proponents. He believes the scientific evidence “suggests that fracking is an inherently hazardous, too risky, dangerous practice that we have no business engaging in at all.”

He also did not want to make another Gasland, the Oscar-nominated documentary by Josh Fox. Gasland highlighted the problem, while Don’t Frack with Denton “is all about showing the process of how people are trying to solve that problem,” he explained.

Graham is a teaching fellow at the University of North Texas’ Department of Media Arts. Beginning in the fall semester, he also will be teaching two undergraduate level classes, Introduction to Radio, Television and Film Audio Production and Introduction to Radio, Television and Film Writing. Don’t Frack with Denton will serve as his thesis documentary for UNT’s Master of Fine Arts Program. The final version will be a 50-minute documentary, with completion targeted for the end of the year.

Graham still hopes to collect more money to complete the documentary and plans to launch a crowdfunding campaign in August. Once the film is finished, he will submit it to film festivals and will try to get it shown on television.

Antiwar activism is where Graham was awakened to the realities of power structures in American society. He also learned how some antiwar activists were motivated more by opposing Republicans instead of genuine opposition to America’s wars. After the election of Barack Obama as president, many liberals who claimed to be antiwar stopped speaking out. “It evaporated overnight and that was concerning,” Graham said.

Graham was eventually drawn into environmental activism through the tar sands blockade in Texas. If Blockadia Rising and Don’t Frack with Denton have colored him as an environmentalist, it is a label he is more than happy to accept.

Making documentary films, according to Graham, is a form of activism. Even filmmakers that engage in the style of documentary filmmaking known as cinéma vérité cannot escape from the role of activist, he emphasized. In cinéma vérité, the filmmaker’s intention is to represent the truth in what he or she was seeing as objectively as possible.

“When cinéma vérité says, ‘I’m just here observing,’ I appreciate that sentiment. But you can’t deny that the very presence of the camera fundamentally changes what’s being recorded,” he said. “That’s why I say all documentary filmmakers are activists, whether or not they are aware of it. If they pretend that they are not, then what they really are is an accidental activist. You’re having an effect; you’re just not aware of it.”

Graham hopes the people of Denton are aware of the positive effect they’re having on Texas politics, even if the city’s fracking ban was ultimately overturned. “People are pissed. And lot of people are being radicalized and disillusioned in a lot of ways” with the passage of H.B. 40, he said.

Denton is not the only jurisdiction to attempt to counter the shale gas revolution in Texas. The city of Dallas did not ban fracking but in 2013 it adopted one of the nation’s most restrictive ordinances on natural gas drilling by requiring more than a quarter-mile between wells and protected uses such as homes. Residents of the city of Arlington, which also sits atop the Barnett Shale formation, have been working to slow down fracking in their community.

“The reason that this happened in Denton is because it’s a much more densely populated suburban area and a college town with a history of political activism,” Graham said. “I really do hope there’s a hornets’ nest of resistance and I’m there to take pictures of it.”

As battles continue between communities and industry, Graham wants activists to understand there will be setbacks but that their efforts are part of a sustainable resistance. “I’ll always be an activist,” Graham said about his own activism and work as a documentary filmmaker. “That’s the price you pay for being an aware, compassionate individual.”