A version of this article ran in the April 2002 edition of CounterPunch magazine.

For the last 53 years, the state of South Carolina has flown the Confederate flag above the grounds of the state capitol in Columbia, a noxious emblem of the state government’s unremitting animus toward civil rights laws and desegregation.

The flag was hoisted in 1962 as a show of defiance against the Supreme Court and the Civil Rights movement. It soon became a war banner for the segregationist minions marshaled behind Strom Thurmond’s Southern Manifesto. The flag has remained a shameful glorification of the ante-bellum, slave-holding South and a daily blight for South Carolina’s black population ever since.

Recall that South Carolina was not only the ignition point for the Civil War, but the Wal-Mart of the slave trade. Many of the black Africans brought to South Carolina as slaves for the plantation owners were sent into the swampy rice fields, which proved to be malarial death camps, where people perished in nearly unimaginable numbers. Nearly two-thirds of the black children in the rice plantations perished before reaching the age of sixteen.

Black Africans who weren’t forced into the rice and cotton fields of South Carolina (the Carolina planters exhibited a peculiar preference for blacks from Senegambia and present-day Ghana) were sold in Charleston’s slave market to plantation owners from across the South. These brokers of human beings ended up making millions and enjoying seats as legislators in the statehouse, where they drafted laws to protect their “property.” When people talk about the flag as a proud symbol of the state’s heritage that’s the inescapable and horrific background.

For the past few of years, the NAACP and local civic rights organizers, including CounterPunch writer Kevin Alexander Gray (click here to read Gray’s bracing history of the battle over the flag), have led a campaign to compel the removal of the flag from atop the capitol building and have it entombed in a display case in a nearby museum, which houses artifacts from what is quaintly referred to in Carolina as “the war between the states”.

When first broached, the demand was met with derision by state leaders and threats of violence from local yahoos. Then the civil rights groups launched a nationwide tourism boycott of the South

Carolina. This was no minor threat. Since the NAFTA-driven collapse of the garment industry, tourism (which consists largely of the ceaseless promotion of the Southern plantation lifestyle) has become the mainstay of the state’s anemic economy. Soon millions were being lost and businesses (which once not so long ago proudly catered only to whites by law and now do so largely based on pricing) started carping to legislators about what could be done to deal with the noisome boycott.

Carolina. This was no minor threat. Since the NAFTA-driven collapse of the garment industry, tourism (which consists largely of the ceaseless promotion of the Southern plantation lifestyle) has become the mainstay of the state’s anemic economy. Soon millions were being lost and businesses (which once not so long ago proudly catered only to whites by law and now do so largely based on pricing) started carping to legislators about what could be done to deal with the noisome boycott.

Ultimately, a so-called compromise plan was brokered by Democrats in the state legislature and the flag migrated from atop the capitol dome to a prominent flagpole on the statehouse grounds, where it flies above statues of Confederate soldiers and generals and other monuments to slavery and the enforcers of racial segregation. Naturally, this satisfied few in the civil rights community and the NAACP boycott remains in place.

Sick of looking at a symbol of terrorism flying on the grounds of the state capital, black activist and brick mason Emmett Rufus Eddy decided that he had had more than enough of this ongoing insult and did something about it. Eddy had tried to pull the flag down on three previous occasions. Even though a restraining order barred him from stepping foot on the grounds of the Statehouse, this time Eddy would succeed.

Assuming the guise of his nom de guerre, the Reverend E X. Slave, Eddy donned a black Santa suit, carried a ladder bearing the names black rights organizers to the South Carolina State House, set it up next to the flagpole, climbed to the top, cut down the Confederate flag, shouted “this is for the children,” and lit it on fire, as state police heckled him from below and tried to douse him with pepper spray.

Apparently, the study of physics and Newton’s law of gravity are not requirements at the police academy in Columbia and the cops were duly surprised when the pepper spray failed to incapacitate the Reverend Slave and instead blew back into the eyes of his would be captors. The officers later filed injury claims.

Eddy clung to the pole, telling his pursuers: “Anybody down there can promise me that this flag will not go back up until my trial?” Eddy asked. “Anybody can make that promise? Make that promise and I’ll come down.”

In South Carolina, old times are not forgotten. The local paper reported the comments of a passing motorist as police tried to pull Eddy down: “String him up right there.” [For the record, there were at least 145 lynchings of blacks by white mobs (ie, homegrown terrorism) in South Carolina from 1882 to 1930, according to the excellent A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings by Stewart E. Tolnay and E.M. Beck.]

Eventually, Eddy was arrested, roughed up a little by the embarrassed cops, shackled and hauled off to jail, to taunts and jeers from a crowd of more than 100 (mostly white) onlookers who had gathered at the site. Within the hour, the Statehouse’s grounds crew secured another Confederate flag (value: $30) and hoisted the infamous banner once again.

The flag may only cost $30 to replace, but the State of South Carolina is determined to impose a much more severe sanction on Eddy. For this modest act of civil disobedience (which some might call a beautification project), Eddy faced a $5,000 fine and three years in prison.

The Reverend Slave was bailed out, but a few days later he was arrested again, supposedly for trespassing on the statehouse grounds, although he was across the street at the time. He peacefully resisted by lying down on the sidewalk and going limp, as the cops hauled him back to jail, one more time.

The Reverend E. X. Slave has shown us the way. Brother, can you spare a match?

Emmett Rufus Eddy was sentenced to two years in prison for burning the Confederate flag, a term that was later suspended with the condition that he never again step foot on the grounds of the South Carolina state capitol. He died in 2005 at the age of 57.

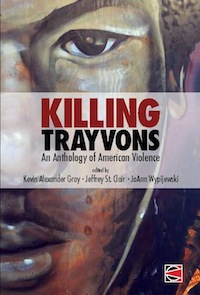

Jeffrey St. Clair is editor of CounterPunch. His new book is Killing Trayvons: an Anthology of American Violence (with JoAnn Wypijewski and Kevin Alexander Gray). He can be reached at: sitka@comcast.net.