Although Marx’s thought settled accounts with bourgeois morality, it remains defenseless before its aesthetic, whose ambiguity is subtler but whose complicity with the general system of political economy is just as profound.

— Jean Baudrillard, “The Mirror of Production” [i]

Taking responsibility for the role of the artist in the machine we call “the art world,” artist Andrea Fraser’s contribution to the 2012 Whitney Biennial of Contemporary Art was an essay in lieu of an artwork. Titled L’1% C’est Moi, Fraser’s essay concluded that: “as our survey of Top Collectors shows, many of our patrons are actively working to preserve the political and financial system that will keep their wealth, and inequality, growing for decades to come.” Tracing the direct connection of museum board members to the 2008 “great recession,” Fraser asks: “[h]ow can we continue to rationalize our participation in this economy?”[ii]

When it comes to the public institutions, though, my answer is that we don’t have a choice.[iii] To retreat is to leave the future of our collective cultural patrimony in the hands of the upper echelon. The extremely inflated price of art at this moment has increasingly transferred control of content away from the hands of professionals and into the sway of laymen patrons, who unabashedly use the institution to increase the value of their private collections.[iv] While some may argue that this has always been the case, financial tools introduced on the art market since the 1980s have been gradually altering the playing field such that the ethical and aesthetic consequences of such patronage for museums is now far graver than they ever were.

The invention of the art-credit system in the 1980s allowed collectors to borrow money against art, potentially turning art into a liquid asset. Together with the development of art advisory boards by major banks and auction houses that taught investors how to collect, the art-credit system formed the economic infrastructure that drove the incremental growth of the art market to its unprecedented magnitude, and to the headline-garnishing spectacle of art’s auction prices today.[v] Art has been recruited to serve the capitalistic venture of inventive profit increase, echoing the broader shift in investment patterns and the boom in market speculation.[vi] During the great recession (which commenced before its public visibility in 2008), the market for art, like that of other luxury commodities, surged to new heights.[vii] Have becoming an acceptable, if not standard, component of a diverse investment portfolio, an asset class if you include real estate or commodities in your definition, art today is fulfilling the potential of its initial liquidization in the 1980s. Consequently, market-based value assessment is exerting direct influence on decision-making for public museums. Rather than divorcing themselves from this structure, public institutions have been subsumed into the system that establishes art’s prices. Today we have two simultaneous dynamics of how value gets conferred on art. In their overlap, wealth wins and a critical idea of what contemporary art may mean suffers.

The museum trove enjoys what we can call for shorthand the modern condition, and which was developed in a slow market. The trove ensures the value of art in circulation, as Baudrillard analysed:

In fact the museum acts as a guarantee for the aristocratic exchange. It is a double guarantee:

—just as a gold bank, the public backing of the Bank of France, is necessary in order that the circulation of capital and private speculation be organized, so the fixed reserve of the museum is necessary for the functioning of the sign exchange of paintings. Museums play the role of banks in the political economy of paintings:

—not content to act as an organic guarantee of speculation in art, the museum acts as an agency guaranteeing the universality of painting and so also the aesthetic enjoyment (a socially inessential value, it has been seen) of all others.[viii]

Under this modern condition art has a double form of value, where works have a monetary measure, a price, (as seen in the recent threats to liquidate the collection of the Detroit Institute of Art in order to pay the city’s debt), and also embody a social value, the combination of the two allows the museum trove to function as a guarantee for an active market. Without the infrastructure of social value art would not be able to circulate.

For the most part, art circulates as a luxury commodity in the sense explained by Michael Heinrich:

Whether or not a particular article is “really” useful for the reproduction of society does not play any role in determining its character as a commodity. A luxury yacht, a video commercial, or tanks are commodities if they find a buyer. And if these are produced under capitalist conditions, the labor expended during their production is “productive labor.” [ix]

The artworks in the museum trove therefore have value because of the work vested in them and because value has been retroactively conferred, and valorised, in the process of exchange.[x] As Christopher J. Arthur observes: “the logic of exchange imposes the same identical abstract form on all goods, namely the value-form, which then develops to capital as the form of self-valorizing value.”[xi] Commodity’s double abstraction in labor and exchange also exists in the work of art, just in different measure.

The process of exchange confers a work’s price. If a work is deemed to be of “museum quality,” its social value is established through institutional accession, and prices for the artist’s works increases significantly. In a slow market, the interval between a work’s initial creation and its paced subsequent circulation generally allowed enough time for verification, making its procurement into the trove less vulnerable to error.

Before the invention of art-credit if you owned a work it would be static until you sold it. The art-credit system positioned art as collateral for credit, allowing its equivalent in money to move.[xii] As an investment incentive, the art-credit system (and the support mechanisms erected to promote art investment) incrementally increased art’s market circulation, recently sped even more by the growing practice of “flipping.” While the accelerating market has made canonized art a more stable investment, this is not the case for unverified contemporary art, where significance has not yet been established, and prices fluctuate like fashions.[xiii] This renders contemporary art an extremely unsound investment for posterity.[xiv] Prices for young art are unstable precisely because the criteria for the assessment of new practices takes time to be established and take effect. The recent museum rush to acquire young art is detrimental, increasing likelihood that we will be stuck in the future with a trove of inferior cultural patrimony.

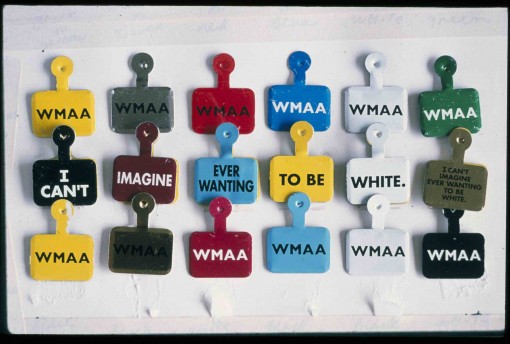

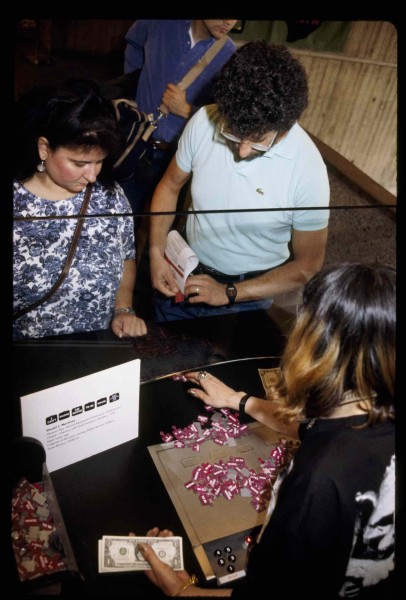

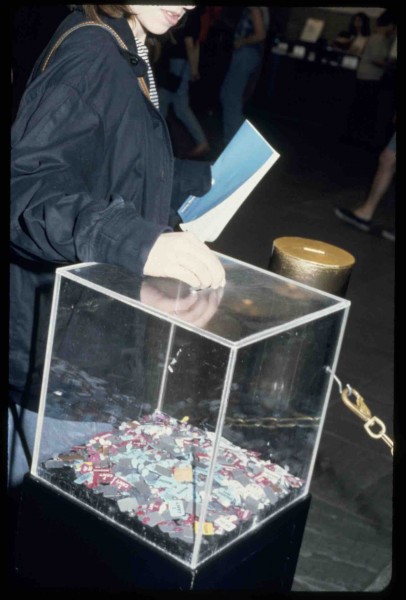

Daniel Joseph Martinez Museum Tags: Second Movement (Overture) or Overture con claque-Overture with Hired Audience Members, 1993 Metal and enamel on paint Courtesy of the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California

Another danger stems from a systematic problem in the ways in which non-profit institutions have been acquiring young contemporary art. Although museums claim that curators are making such decisions, it is common knowledge in the field that increasingly it is individual donors siting on acquisition committees or foundations that are deciding which work they “give.”[xv] Contemporary art foundations in the US function as tax havens that serve wealth while arguing that they operate for the social good.[xvi] We have to ask what types of professional standards, processes, or procedures are practiced in these foundations, and who is it that supervises or regulates them. In many cases it is laymen/women collectors deciding what art is significant or what activities might be considered public service.

When museums have become valorization machines in the service of wealth, the term “anti-trust” may not be far-fetched. Mandated or charted to hold works “in the public trust,” most non-profit private museums benefiting from tax-exempt status are governed by trustees. If institutional benefactors are serving their personal interest and not a public notion of qualified art, then this is a condition of anti-trust.

Relying on the logic of value largely formed under the conditions of modernism, museums are using the wrong measure to gauge the significance of contemporary art. I am not claiming that professionals can predict the future, however, historians and curators have a better chance of assessing long-term contribution than do laymen collectors. Ideally, professionals possess a commitment to attempt objectivity. Museums should be held accountable to such standards.

Given the new logic of art’s circulation we need to rethink verification and assessment of art’s significance outside its monetary value. In Value-Form and Avant-Garde, an account of modern art as a series of negations, Daniel Spaulding shows how the modernist work of art negotiated the boundaries of its own definition, a central limit being the commodity form:

In any given instance of modernism at its highest intensity it was the possibility of the mark itself that was at stake: whether line or colour or shape could be adequate to history and still be recognizable as art, and whether the artist’s subjectivity could be adequate to the making of such marks. Modernism mediated that limit and made it into form. Art courted reification when it failed to confront the limit of its reproduction as an institution – whenever, in other words, it started to look too much like art – yet it risked still more disastrous reification when it exceeded that limit […]. Either possibility was built into modernism’s basic procedures.[xvii]

Temporality sustained Avant-Garde art as a “special commodity,” progress of time allowing it to remain suspended between the value-form and its negation.”[xviii] That “Modernism mediated that limit and made it into form,” was dependent upon the relative operation of negation (since the moment when value is conferred upon a work is also the moment it is subsumed into the system of capital). Following Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory Spaulding explains how art sustained its negative work:

Under capitalism, art is and is not like any other commodity. It is and is not like any other congelation of abstract labor time. It occupies something like a permanent gap in the structure of value’s reproduction, and hence is in contradiction with the value-form even as it is nothing other than this relation to it. During the epoch of programmatism, it was the specific form of this contradiction that accounted for art’s positivity, as a practice that was able to sustain itself, indeed to thrive on its predicament, at least for a time. Modernist art was also negative because it stood for everything beyond the law of value. In certain of those extreme moments that defined its very being, it was nothing less than the concrete figure of utopia. As such, however, it perhaps remained a specific and conflicted instance of the value-form’s own properly utopian content, which is to say its prefiguration of a socialist mode of production that would be even more thoroughly mediated by labor than is capitalism, though under the conscious direction of its human bearers. […]

Art could play this role only by continually defying its relapse into identity with the value-form. This required an immense labor of the negative. At the same time, art had to assure its reproduction as an image of value’s blocked totalisation, which is to say, as an image of the dictatorship of the proletariat, or the transitional phase, or any other placeholder for a future social order grounded on labor in the form of value and hence on reproduction of the class relation.

Today the situation is different. Due to the art-credit system any practice that is successful on the market becomes identical with the value-form. Recast as equivalent to money, art has been recruited to serve the logic of finantialization as a form of value that mediates between other transactions. This may take place regardless of the method or attitude taken by the artist. Sold in art fairs, Daniel Buren’s conceptual stripes, once subversive, have now, by his own volition, collapsed back into the abstractions they once aimed to critique. I do not intend to deny artists profit from their past glory, but rather to recognize that what were once gestures of negation have become part of a standardized vocabulary arsenal, a way to derive more surplus value from the art by placing it within a genealogy. Professionalization and networking opportunities offered in lucrative MFA programs have bred a new generation of artists savvy at activating conceptualism as a business model. Postmodernism has allowed for a revival of every mode of attitude and style in art. Figuration and abstraction exist simultaneously and there is little left to negate. Once analytic, today formalist and abstract practice or discourse provides excellent border and culture-crossing currency—ready for consumption by totalitarian wealth from the Gulf to Russia and beyond. Abstraction today is currency.

Daniel Joseph Martinez Museum Tags: Second Movement (Overture) or Overture con claque-Overture with Hired Audience Members, 1993 Metal and enamel on paint Courtesy of the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California

As synchronicity and simultaneity of practices are the current logic of art we face a paradox—where a relatively static trove, reliant on the value-form logic of the modern art object, is what confers the possibility of value on a rapid market. In its static form the Avant-garde (as a period, as an idea, as a set of practices) functions as the reserve upon which the circulation of contemporary art draws its claim to value. Since rarity and scarcity are still (and forever) the status of modern art, we can attribute its enormous prices to the conditions of the market. However, for contemporary art, where contradictory claims of oppositional practices have been collapsed for the sake of profit, this is no longer the case. Although often claiming the seriality of minimalism, Pop, or Conceptual art, the vast majority of contemporary art confirms the logic of the limited edition luxury object as types of mass-produced hand-made objects; functioning like the pre-modern master’s workshop (with studio assistants replacing apprentices) while banking on ideas whose currency belongs to the “post studio” impulse. For example, up to a certain point in his career, the significance of Gerhard Richter’s work is undisputable, but his later production relies on notions of genius à la Jackson Pollock, negating the cerebral thrust of his early work, and much of his intellectual justification. The world is awash with objects, with no basis in sight to distinguish one from the other. Auction-house blurbs and gallery press releases efficiently appropriate a modernist language of connoisseurship, but to no avail, justifying value with hyperbolic language jokingly identified by the literary journal Triple Canopy as “International Art English.”[xix] Prices, nevertheless, continue to rise.

The current market has pushed museums out of the game—they simply cannot afford the art, leaving them to rely on donations for acquisitions.[xx] When it comes to historically verified art this does not pose a theoretical problem, but when it comes to contemporary art a blatant conflict of interest is introduced. This is not news; critics and historians have commented on questionable nature of “art-world” transactions.[xxi] Infamous for lack of regulation and transparency, the art market benefits from the allure of mystery attached to how sales are conducted.

As is also well known, dealers often “place” works in collections, choosing what to sell and to whom, activating the lure of withholding to their advantage. Thus for example a dealer wishing to promote a young artist will sell their work to a new collector on the contingency that the collector purchase two works and donate one to a museum of choice, in effect committing a public institution to years of research, care, and other resources required to maintain a work of art. Another example of accession under coercion takes place when curators make wish lists but foundations eventually choose works by which artist to donate, enforcing taste and opinion in institutions where objectivity is an ethical imperative. Dealers, collectors, foundations, and private museums make sure that information remains shrouded, as employment in many of these institutions is often contingent on signing secrecy agreements.

Daniel Joseph Martinez Museum Tags: Second Movement (Overture) or Overture con claque-Overture with Hired Audience Members, 1993 Metal and enamel on paint Courtesy of the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California

With a specific caveat, a recent exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) can prove my point. It is not my intention to single-out the LACMA, but I do so precisely because I hold it in such high esteem and have written favorably about other projects presented there in the past. As a case study it reflects a structural problem replicated far and wide. Variations: Conversations in and Around Abstract Painting (2014-2015) featured, according to the museum website: “29 artists whose work reflects the language and style of abstraction.” The inaccuracy of calling abstraction a “style,” is indicative of the misguided curatorial attitude, as is the second sentence of the introductory wall-text that reads: “Most recently, abstraction has dominated painting, viable with critics and urged by the marketplace.” Are these the qualifications for an exhibition at an encyclopedic museum? Is this a theory of contemporary art? The contribution of the curatorial gesture in Variations is rendered meaningless, as it consolidates artists whose practices do not necessarily engage methodically with the question of painting or abstraction, thus that the exhibition affects neither a point of view on questions pertinent to painting, nor a statement on contemporary art. Based on recent acquisitions the show does boast several works that have already proven to be of merit, either through their critical import or influence on other artists. However, since they are inappropriately contextualized, their clear and distinct social commentary comes under erasure. The impulse to render them abstract is the impulse to turn them into currency, catering to the collector class that some of the included works are actually aiming to criticize.

For many included works there seems to be no criteria for verification other than market success, as they have little to no track record of critical writing or institutional exhibition. Catalogues produced by commercial galleries do not count as verification, as they have no system of external review. Many of the works in the exhibition, as competent or beautiful as they are, have yet to make any contribution to the field, and many do not have the ambition or the capacity to do so. Why would an encyclopedic county museum accession works that belong on a wall in a domestic setting? In a bubble market the irony is that for the same price of an artist younger than thirty years, whose success is utterly speculative, the museum could acquire work that has already been historicized. Museums should not participate in the game of speculation.

The paradoxes of the contemporary art world have been the subject of artists engaged in critical practice. Daniel Joseph Martinez and Andrea Fraser have dealt with these questions astutely. Not one of the many critics that attacked Martinez’s contribution to the 1993 Whitney Biennial identified that the piece was conceived in response to the development of the art-credit system, which was gaining traction by the late 1980s and early 1990s and was substantially discussed in news-media. In Study for Museum Tags: Second Movement (Overture) or Overture Con Claque – Overture with Hired Audience Members (1993), Martinez replaced the Whitney’s color-coded museum admission buttons that usually spell WMAA with fragments of a sentence as follows: I CAN’T/ IMAGINE/ EVER WANTING/ TO BE and WHITE, as well as a button including the entire sentence. Falling into the obvious trap of reading the work only through its racial signifiers, critics entirely missed the work’s focus on the moment of box-office transaction, and the fact that the artist had given visitors a work of art for the price of admission. Visitors, it seems, appreciated the gesture, many hanging on to their entry tag, as evidenced by the empty recycling box at the museum’s exit, habitually full at other exhibitions.

In Untitled (2003) Fraser targeted the transaction as a site of intervention for the contemporary artwork. Through her gallerist the artist contracted a collector, who already owned several of her works, to have a 60-minute sexual encounter in a hotel room and to produce a video, in an edition of five. The silent run of the event is intended for display on a small monitor, perched on a single pedestal, in an otherwise fully lit empty gallery. The real scandal of the work is not the sexual encounter, in which Fraser had relative agency. The artist is not presented as a victim but as a participating agent on equal footing as the collector, focusing the problem on the system and not on the individual participants. The real injury is the subsequent valorization of the artwork independent of the artist, since, as Fraser has emphasized, the work will always be sold for more than she had been paid. “Everyone was obsessed with the sum,” she recalls, and for this reason refuses to disclose it.[xxii] Insisting on the distinction between price and value, the point is also that the harm of a systematic condition is ultimately registered on the body, showing the relation between the operation of transaction, and the formation of the subject.

Solutions and Ideas

It is not my intention to call the state on museums—no one today wants to be caught dialing 911.

Instead, a simple solution: public museums should stop acquiring young art.

Think about it, what does owning very recent art mean for a posterity-based institution? Public museums should pay wages to living artists for displaying work, but refrain from acquiring it.[xxiii] Real museum patronage is to support such programs, with no personal agenda. For the price of the work of a young artist the museum could acquire a work by a 1970s-1980s feminist artist whose significance is established not only by critical writing and exhibitions, but also by a living record of influence on subsequent generations of artists. Why then would a museum accession a lesser equivalent? Let us leave the unverified art to private collections—have them take the inevitable risk of buying based on market criteria.

What exactly the “verification window” for recent art might be or mean is up for debate. We could propose, say, a twenty-year waiting period, or a set of interlocking criteria, adding, for example, a requirement that critical texts on the artist exist, written at a historian or critics’ own volition, or for a peer reviewed or otherwise juried institution or publication, again, without any form of persuasion by interested parties. Acquisition processes should be conducted through peer-reviewed systems, or other modes of democratic-process criteria, such that it is not the market or wealth that will determine what is chosen for us to maintain, store, study, display and keep for posterity. Models exist. One major example is the New Museum under the direction of Marcia Tucker from 1977 to 1998.[xxiv] Describing how the structure influenced radical programming Juli Carson writes:

This administrative model was one that more greatly valued the theorizations of institutional critique by artists […] than that of nineteenth-century museum practice continued into the twentieth century by museums such as MoMA, the Whitney, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[xxv]

The works of artists mentioned by Carson (Buren, Hans Haacke, Michael Asher, Robert Smithson, and Laderman Ukeles) pointed to the hypocrisies and deficiencies of the art institution and its ideologies. Although many today mourn the agency of institutional critique as defunct, I believe its ideas can and should be revived as institutional policy. Revisiting and developing alternatives offered by artists or figures like Tucker is possible. The first move is to split the public and private use of art, and then—let history be the judge.

Dr. Nizan Shaked is Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Museum and Curatorial Studies and California State University Long Beach. Her book the Synthetic Proposition: Conceptualism and the Political Referent is forthcoming with Manchester University Press for the series: Rethinking Art’s Histories (edited by Amelia Jones and Marsha Meskimmon). She can be reached at Nizan.Shaked@csulb.edu.

Notes.

[i] Jean Baudrillard, The Mirror of Production (St. Louis: Telos Press, 1975), 39.

[ii] See Andrea Fraser, L’1%, C’est Moi, 2012. <http://whitney.org/file_columns/0002/9848/andreafraser_1_2012whitneybiennial.pdf>.

Fraser retells in note number 23:

“I began much of this research in the spring of 2010, when Artforum asked me to contribute to their summer issue on museums. Artforum declined to publish the text I submitted, which detailed the involvement of MoMA trustees in the subprime crisis”

The suppressed text was eventually published in Texte zur Kunst 83 (September 2011): 114-127.

[iii] The vast majority of institutions in the U.S. are public/private partnerships with non-profit status. My use of “public” here addresses tax-exempt institutions that receive public monies and are mandated or chartered to hold collections in the public trust.

[iv] See Isabelle Graw, High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture (Berlin and New York: Sternberg Press, 2010).

[v] On patronage and the development of the art-credit system see my “Something out of Nothing: Marcia Tucker, Jeffrey Deitch and the De-regulation of the Contemporary-Museum Model,” Art and Education <http://www.artandeducation.net/paper/something-out-of-nothing-marcia-tucker-jeffrey-deitch-and-the-de-regulation-of-the-contemporary-museum-model/>.

Also see Noah Horowitz, Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2011). Horowitz rigorously considers a range of events that led to the current art bubble, but in my opinion underestimates the significance of the art-credit system as the critical event that made art compatible with the neo-liberal global economy.

[vi] On the speculative boom see Tony Norfield, “Derivatives and Capitalist Markets: The Speculative Heart of Capital,” Historical Materialism 20, no. 1 (2012): 103–132, 117.

[vii] Bijan Khezri, “The New Art of Art Finance,” Wall Street Journal, Sept. 19, 2007, D10.

[viii] Baudrillard, For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (St. Louis: Telos Press, 1981), 121-122.

[ix] Michael Heinrich, An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital, trans., Alex Locascio, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012), 122. According to this logic necessary labor time for an artwork would include the means to sustain the artist and her/his practice.

[x] I rely here on Endnotes, “The Moving Contradiction: The Systematic Dialectic Of Capital As A Dialectic Of Class Struggle.” <http://endnotes.org.uk/issues/2>

[xi] Christopher J. Arthur, “Towards a Systematic Dialectic of Capital,” 6. <http://chrisarthur.net/towards-a-systematic-dialectic-of-capital.pdf>.

[xii] This allows art to fulfill what Heinrich describes as the second function of money, which is to facilitate circulation. See Heinrich, 66.

[xiii] The website ArtRank.com purports to quantify the contemporary art market objectively. Ironies of the word “rank” notwithstanding, it demonstrates the speed in which emerging artists rise and decline. This fickle nature of the art market has created tremendous problems for such novel experiments as the art pension fund. See Daniel Grant, “A Retirement Account for Artists: At 10 Years Old, the Artist Pension Trust Is Bigger, But can it make money?” The New York Observer (12 February 2014). <http://observer.com/2014/02/a-retirement-account-for-artists-at-10-years-old-the-artist-pension-trust-is-bigger/>.

[xiv] The “informationally inefficient” art market and the volatility of prices are discussed in Jaclyn McLean, “Finance Nouveau: Prospects For The Securitization Of Art,” New Mexico Law Review 38, no. 3 (Summer 2008): 561-586.

[xv] Several artists have shared with me their observations under conditions of anonymity.

[xvi] Carol Kino, “Welcome to the Museum of My Stuff,” The New York Times, 18 February 2007.

[xvii] Daniel Spaulding, “Value-Form and Avant-Garde,” Mute (27 March 2014).

[xviii] Stewart Martin, “The Absolute Artwork Meets the Absolute Commodity,” Radical Philosophy 146 (November/December 2007).

[xix] Alix Rule and David Levine expose the vacuous nature of much art writing in “International Art English,” Triple Canopy <http://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/international_art_english>.

[xx] Lee Rosenbaum, “Museums can’t compete,” The Los Angeles Times, 4 September 2007.

[xxi] Graw writes: “Practices that in other fields would be denounced as criminal or insider-trading are commonplace in the art market.” Graw, 101.

Also see: Judith H. Dobrzynski, “A Growing Use of Private Art in Public Spaces,” The New York Times, 16 March 2011.

[xxii] Andrea Fraser, Lecture, California State University, Long Beach, February 24, 2010.

[xxiii] In the US see Working Artists and the Greater Economy <http://www.wageforwork.com/>.

[xxiv] The acquisition program for the New Museum in its original iteration was actually quite the opposite of what I suggest; the original plan was to hold works for only ten years, which proved to be unsustainable. My point here is that we should continuously attempt to rethink received administrative structures. Marcia Tucker proved that rethinking and restructuring is utterly possible. Records of correspondences, board meeting minutes, and other documents held in the Marcia Tucker Papers, 1957-2004, Getty Research Institute Special Collections, reveal that Tucker drove a hard line convincing patrons to follow her vision in persistent and strong terms. Today’s museum leadership seems to surrender to patron taste rather than, like Tucker, work to form it.

[xxv] Juli Carson, “On Discourse as Monument,” in Alternative Art New York: 1965-1985: A Cultural Politics Book for the Social Text Collective, ed. Julie Ault (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press in collaboration with the Drawing Center New York, 2002), 121-157, n.44.