More than a month has passed since the Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris. How should we understand this dreadful massacre? That if you insult a minority that then a few individuals within that group might come after you? Or is it perhaps much worse than that, as some will have us believe, and that freedom of speech is under threat?

Demonstrations were held throughout France supposedly in defence of freedom of speech. As many writers have pointed out, the demonstration in Paris was attended by world leaders that—to put it mildly—don’t seem to find freedom of speech all that important in their own countries. One of the survivors of the shooting, Laurent Léger, lambasted the hypocrisy of Western governments who pretended to stand up for freedom of speech. [1] In fact, France seized the opportunity to crack down on ‘hate speech’. [2]

But the world leaders’ presence, despite their faulty records, is nonetheless understandable; they attended the demonstration to express their commiseration, and that’s perfectly fine.

Yet, the ‘freedom of speech’ aspect bothers me. It is an attempt to take this shooting out of its political context, to describe it as a story of two young Muslims who saw a cartoon, and got so angry that they decided to kill eleven people.

The fact of the matter is that the two terrorists didn’t care about freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in France. They were radicalised by the U.S.-led Western interventions in the Muslim world, and in their frustration over the endless killing that’s going on there, they decided to exact vengeance. In their eyes, Charlie Hebdo was a perfectly logical target because it had become a symbol of anti-Muslim mockery.

The message the perpetrators wanted to send is clear: if you continue to attack us, then you’ll pay for it. For a long, long time the West has been able to carry out bombing campaigns, invasions and occupations, stage coups d’état and targeted killings in other parts of the world, without fear of revenge attacks at home. Not so anymore.

Reducing the Charlie Hebdo shooting to a question of freedom of speech is convenient because it allows us to ignore the misery caused by Western interventionism, which ultimately led to the Jihadist resurgence. Massacres and shootings carried out by Muslims, like the ones we saw in France, are now an everyday occurrence in countries that have been ‘blessed’ with Western intervention. Though Islamist groups carry out occasional terrorist attacks in the U.S. and Europe, it is in the Mideast where most of their victims are to be found – and the greater majority of their victims there are Muslim. This is the ‘New Middle East’ that the neo-conservatives in the Bush Administration envisioned when they plotted the Iraq War. [3]

But this is not the only reason for my scepticism towards the ‘we must stand up for freedom of speech’ crowd. Although this is a right that must be defended, it is important to do so without being hypocritical. Charlie Hebdo mocked Islamic figures, and when they were criticised and threatened for doing it, they made a point of not backing down. Instead, they kept publishing such cartoons, which they have every right to do. While this may seem admirable, or even heroic, the magazine doesn’t always stand its ground.

In 2008 Charlie Hebdo was criticised for ridiculing Judaism. Though the magazine had stood up for freedom of the press when it came to mocking Islam, in that case cartoonist Siné was asked by his editor Philippe Val to apologise. When Siné refused, Val sacked him. Siné also received a death threat on a website run by the Jewish Defence League (JDL). There is clearly a double standard being employed by Charlie Hebdo, and it’s not alone.

A similar incident occurred at the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which published the infamous prophet Muhammad cartoons. An Iranian newspaper said that in response it would hold a contest with cartoons mocking the Holocaust as an analogous – and offensive – way to test the limits of freedom of speech. The culture editor at Jyllands-Posten, Flemming Rose, likely not wanting to be seen as a hypocrite, said he would consider publishing these cartoons. Upon hearing this, however, Jyllands-Posten’s editor-in-chief, Carsten Juste, declared that his paper would publish the cartoons “in no circumstances,” called the Iranian contest a “tasteless media stunt” (unlike his own provocation, I suppose) and urged Rose to “take a vacation.” The editor of the newspaper’s Sunday edition, Jens Kaiser, had a few years earlier turned down cartoons of Jesus’ resurrection, telling the cartoonist that they would “provoke an outcry,” although he later said the real reason was because the drawings were sub-par. [4]

Blatant hypocrisy, or unintended bias? To many Muslims this double standard is hard to grasp, and it makes them feel even more outraged. However, there is an explanation for it.

It is important to understand that the criticism stems from different sources. When anti-Muslim cartoons are published, it is mostly the Muslim community that objects. The reaction under these circumstances from what one can call our ‘elites’ – politicians, editors, journalists, mavericks, etc. – is that no matter the content, freedom of speech must be defended at all cost. This elite responds very differently, however, to cartoons containing anti-Jewish mockery: all of a sudden, the content does matter. It is then characterized as a question of ‘hate speech’, not freedom of speech.

The Iranian newspaper chose to focus on a subject it knows to be a Western taboo. In a number of European countries Holocaust denial has even been criminalised (France included), yet you don’t see newspapers publishing texts that question the Holocaust to test the boundaries of freedom of speech. (If anything threatens freedom of speech, it is government-imposed restrictions of this kind.) The issue is so sensitive that even publicly defending the right to question the Holocaust is often regarded as support for Holocaust deniers, and those who occasionally dare to do so invariably make sure to emphasise their utter dislike for the people whose rights they are defending.

Around 50 million people perished in World War II, including 5 million Jews. It was a huge disaster, not least for Europe. European school children of today are taught about the anti-Semitic propaganda disseminated by the Nazi regime and how it enabled the extermination of European Jews. They are taught that anti-Jewish hatred and propaganda is dangerous because we know what it ultimately leads to: genocide.

This is why many Europeans (including our elites) respond emotionally to what they perceive as being anti-Semitic, while they don’t respond as emotionally to other forms of racist propaganda, including Islamophobia. This is the reason for the double standard. To oppose anti-Semitism is a value of the elite, and editors that act in violation of this value will be treated like outcasts. A magazine can make a point of printing anti-Muslim mockery in response to threats because it knows that freedom of speech (and of the press) will be vociferously defended by the elites of Europe when the target is Muslim, whereas anti-Jewish cartoons will generate harsh condemnations.

So when Charlie Hebdo or Jyllands-Posten mocks Islam, they are not really testing the boundaries of freedom of speech. And when an Iranian newspaper mocks the Holocaust, it’s not doing so either. If challenging taboos was their purpose, then the Iranian newspaper would publish anti-Islamic cartoons and Europeans magazines would run articles questioning the Holocaust.

What about anti-Christian satire then? If a ‘Christian’ newspaper in the West mocks Christianity it would not cause much fuss because it is no longer a taboo. But if a group such as ISIS did so while persecuting Christians, it would not be regarded as satire.

In short, context matters. That’s why we should not expect the publication of anti-Muslim cartoons while Muslim countries are being bombed and invaded to be perceived as harmless, just like the anti-Semitic cartoons published in Der Sturmer in hindsight cannot be presented to the world as ‘testing the boundaries of freedom of speech’.

Source: http://normanfinkelstein.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/sorry-charlie.jpg

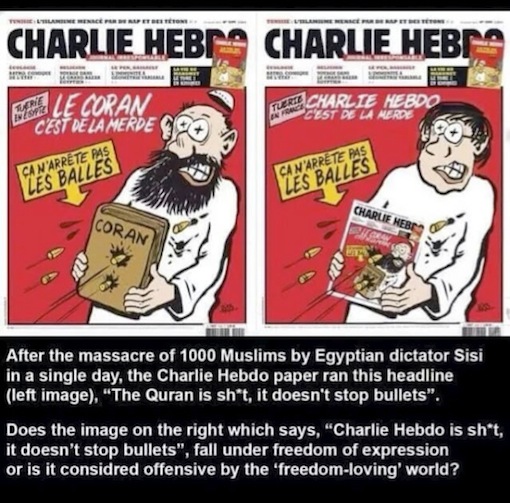

After the massacre in Egypt in August 2014, that claimed the lives of maybe 1,000 people that protested against the Sisi regime, Charlie Hebdo mocked the victims by putting a cartoon on the cover of a Muslim man being shot. The text reads: “The Koran is shit, it doesn’t stop the bullets.” After the Charlie Hebdo shooting someone manipulated the cartoon and changed the text to: “Charlie Hebdo is shit, it doesn’t stop the bullets.” It would have been a suitable cover for the first Charlie Hebdo issue after the tragic shooting, and I’m sure the victims would have appreciated the satire.

Kristoffer Larsson lives in Sweden. He can be reached at krislarsson@gmail.com

Notes.

[1] Survivor of ‘Charlie Hebdo’ Massacre ‘Very Happy Obama Didn’t Come to Paris’, Jonathan Schwarz, Huffington Post (26/1/2015); http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jonathan-schwarz/survivor-of-charlie-hebdo_b_6543718.html

[2] France Arrests 54, Announces ‘Hate Speech’ Crackdown, Jason Ditz, AntiWar.com (1/14/2015); http://news.antiwar.com/2015/01/14/france-arrests-54-announces-hate-speech-crackdown/

[3] Clean Break or Dirty War? Israel’s Foreign Policy Directive to the United States, IRmep (3/27/2003); http://www.irmep.org/Policy_Briefs/3_27_2003_Clean_Break_or_Dirty_War.html

[4] Cartoon row editor sent on leave, BBC News (2/10/2009); http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4700124.stm