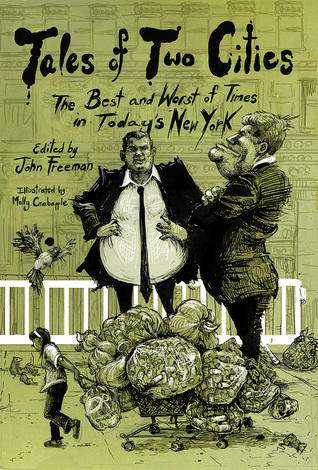

Tales of Two Cities: The Best and Worst of Times in Today’s New York

OR Books (2014)

290 pages

Available in paperback and as an e-book

When I was driving with my family back to England from a day trip to Dunkirk Beach, a French border guard in Calais told us at the Chunnel entry that America was under attack (did I detect a smile?). Later, back in Surrey, we watched the Sky news broadcast of the Twin Towers collapse, as neighbors in our cul-de-sac partied, fireworks and all (were they immune to the situation’s gravity?). Already a longtime ex-pat by then, the distance in time and space led me to respond not with the ululations for vengeance heard across the US mediascape that day but with an echo of my young daughter’s query –“Why?”

As circumstance would have it, almost two years later I visited a friend in lower Manhattan. The reek of horror smoke was still in the air. I wanted to visit Ground Zero, but my friend talked me out of it; maybe, being a psychotherapist, she was sensitive to overexposure to the still-suppurating trauma. In a deft segue of optimism, she said that while not much good had come out of the attack, one silver lining was the kindness New Yorkers were now showing each other, the deference to a shared fragility – the Big Apple, of all locales, had become what G. H. W. Bush had once called for: ‘a kinder, gentler place’.

But no human good seems to last forever, or else it’s always there but gets transformed, perverted, and tremendous amounts of focused will need to be applied to recover it for redemption. Matter can neither be created nor destroyed, not even love. Yet dark energy pervades all, and it didn’t take long for the ageless pathological sharks and charlatans to see a way to make a buck off unspeakable grief and spiritual violation. The financial meltdown of 2008, a crisis which forced Obama’s hand even before he had been inaugurated, was the result of machinations years in the making, the other side of the now-counterfeit coin of contemporary capitalism – no one was there to punch the New Gordon Gekko in the mouth, and what the Triffids did to the towers and symbols That Day, Wall Street snorkel porkers in the treasure trough did to the economy: Make it scream, they cried, and it did.

The divide between the haves and have-nots has grown exponentially since, with New York a focal point because it remains the crucible of a corrupt capitalism and the main barometer of zeitgeist pressure systems exploding the world. The corrosion has been well-documented in such films as Park Avenue.

Is it any wonder that most Americans don’t seem to care if the torture works or not? They just need to hear a scapegoat scream. Turns out Americans live in Guantanamo cells of debt service, credit defaults, slaves to desires stoked by deus in machina algorithms. That’s you on that stool with a hood and a neck noose in the dark. Spend, purge, make room for ever more, barks the dog-god at your feet, Bulimius. And even ‘freedom’ leaves nowhere to go, because no one wants an Equifax credit ratings flunky in their midst, any more than they want terrorists. Kick the stool out: Clint Eastwood’s sniper ain’t coming to save you this time. Punk.

I was thinking of all this, and more, as I waded my way through Tales of Two Cities, a marvelous collection of some 30 narratives about contemporary life in New York City, edited by John Freeman, a former editor of the literary magazine Granta. For today, New York is largely back to being the cold, divided, rude split city it never really stopped being, even in its collective grief a decade ago. Back then, in those early healing days, it was perhaps unimaginable that cops would be shot to death in “revenge” for political events — lockdowns, repressions, all police state stuff– so newly appreciative were people for the perceived sacrifices of those who put their lives on the lines to serve and protect, who put out blazes, and who had suffered so much loss on 9/11. Economic erosion, class divides, rampant homelessness, feudal wages, deregulated rents, grim future tidings – these are the leit motifs of Tales.

The collection is packed with slice of life tales as varied as NYC pizza pies – with all the toppings: enormous energy, sage street wit, winsome wisdom, and the grit of Truth. And, I reckon, it would be worth the purchase for Zadie Smith’s edgy comical corset saga alone. But it’s a volume chock full of surprises: There’s Lawrence Joseph’s dazzling lyrical poem; bolshy transgenders; a Czech car mechanic (or is he Serbian?); a widowed former Red Cross chaplain turned bar tender dealing with power games of the entitled; gentrifying landlords driving out tenants by neglecting to heat their flats in mid-winter; Junot Diaz’ tale of reciprocal burglary; Bill Cheng’s memoir of being stuck in a hidden, forgotten cubicle writing copy that celebrates rags to riches go-getters; and so on.

We learn from Valeria Luiselli that “the area now occupied by Columbia University’s Morningside campus was the lunatic asylum until the late 1800s,” and, she adds devilishly, “The city must have been full of them—colonial lunatics, maddened by their own expansionist ambitions, souls sickened by solitude and nostalgia, minds turned against themselves for having seen too much—for having undone so many.” We learn that “the top fifth of the population here earns more than thirty times that of the lowest fifth.” And then Teju Cole treats the reader with samplings of fait divers (small fates), a French form of condensed journalism that attempts to capture the 5Ws in a sentence or two. For instance, this gem of the form: “Lorenzo Corello and Annie Pollilcolski, in Jersey City: love was his question, no her answer, a razor his riposte, critical her condition.”

Tales of Two Cities has been likened as a kind of postmodern update of Jacob Riis’ classic How the Other Half Lives, but that comparison, while valuable in a way, does not deliver full justice to either Riis’ work or to Tales. Riis’ 125 year old narrative is as confronting a black and white study in sociological depravity as any student of popular history is ever likely to read. It should be mandatory reading in high school, along with Howard Zinn’s The People’s History of the US, which it likely inspired.

Riis describes and catalogues the rise of the tenement system in an overcrowded turn-of-the-century New York, which is what ‘the other half’ refers to (although, as Riis points out, by the time of publication upwards of three-quarters of the population of NYC lived in tenements). He describes a ramshackle crazy quilt of unsafe structures reminiscent of Dr. Seuss, where a typical apartment consisted of “one room 12 x 19 with five families living in it, comprising twenty persons of both sexes and all ages, with only two beds, without partition, screen, chair, or table.”

And deeper within these structures were “cave dwellers” composted by the dozens in single rooms without light or ventilation. Who lived in these miserable, cholera-permeated hovels? European immigrants flooding in for ‘a better life’ than what they left behind in London, Paris and Old Praha: Irish, Italians, Germans, Serbs, French, Spanish, Russians, Chinese. “Give me your unwashed huddled masses,” says the sign over Ellis Island, which could have been written by a slumlord, who might have added, “We know just where to crush their spirits and rob them blind.”

Unlike Tales, there is no kinetic energy in Riis’ narrative: pestled people survive mortars of greed and rapacity in miracles of resilience that almost defy human understanding. Such tenements are gone today, although rising rents, relentless un- or under-employment, and the tyranny of debt are forcing sharing situations unseen since at least the Reagan era. But Tales does share with the Riis study a series of snapshots of immigrant life in New York, for almost all the Tales are from the point of view of ‘foreigners’ or ‘hicks’ come to the Promised Land for a better life, just as they did more than 100 years ago.

However, instead of being herded and crushed into matchbook firetraps, some landlords not averse to setting their own tenement towers on fire for insurance, the human loss not factored into the profit, today’s immigrants largely live on the edge of physical survival and often close to falling into the abyss of despair. Today New Yorkers are composted in digital databases, and breathe in the dark, fetid air of compartmentalized debt they cannot escape. Call it: A Tenemental Journey.

Of course, Tales does contain grim reminders of the Riis “cave dwellers”, but this time in the form of the huddled masses who live like Morlocks beneath Manhattan’s surface, the tunnel dwellers, or ‘Mole People’ as the dailies call them. In “Near the Edge of Darkness,” Colum McCann went on an investigative journey of this underbelly and relates his experience thusly,

“The idea of living underground, in the dark, feeds the most febrile part of our beings. The tunnels operate as the subconscious minds of our city: all that is dark and all that is feared, pulsing along in the arteries beneath us. There are seven hundred miles of tunnels in the city. The capacity for shadowplay is infinite. There are hundreds of nooks and crannies, escape hatches, ladders, electrical rails, control rooms, cubbyholes. An overwhelming sense of darkness, made darker still by mall pinpoints of light from the grates of topside. And then there are the rats, in singles, pairs, dozens, sometimes hundreds at your feet. If anything can happen, the worst probably will.” Here is a milieu of madness, of the unconscious turned physical, the Minotaur’s labyrinth come alive.

McCann continues his Cabeza de Vaca-like adventure into the unknown interior of America’s greatest city and discovers it gets darker still: “A consequence of darkness is mystery. The farther underground I went, the more mysterious the people became. A pair of runaways. A Vietnam vet. A man rumored to have once worked for CBS. A former University of Alabama football player who now looked at his life through the telescope of a rack pipe. Bernard Isaacs, a man with long dreadlocks who called himself Lord of the Tunnel. Another man, Marco, a flute player, who lived in a cubbyhole in the rafters and wanted to be known as Glaucon. And Tony, a pedophile who pushed his shopping cart full of tiny teddy bears along the edge of the tracks.”

These are misfits, down-and-outers too far gone even for Tom Waits to rescue in song; a Lonely Hearts Club Band, maybe even too damaged to raise a glass in Charles Bukowski’s Barfly orbit. This is a Night Gallery that stirs and shakes the soul. If you were looking for T.S. Eliot’s “madman shaking a dead geranium,” you’d find him here, now, in the present, giving the lie to the notion of progress in the great tarantella dance of dialectical materialism.

There are other compelling visions and voices worth singling out as well. There’s the almost-archetypal Indian cabbie with a postgraduate knowledge of some obscure facet of myth, cultural anthropology or the like. Taiye Selasi describes one such cabbie as he hauls a rich Russian émigré uptown, his heart broken by his daughter’s American drive for independence: “The Indian man finds this lovely. He is not a cabbie, but the ferryman Charon. One who delivers. Attends to transitions. Bears witness, gives refuge with sound, scent, and story to travelers trapped between points A and B.” Tales is full of such myth-living in-the-making.

Indeed, Tales of Two Cities is all about myths, delusions, and debunked dreams – American, foreigner, human – and you don’t know whether the accompanying riff should be a Mile Davis blues, or Shostakovich cello chiller, or a ragged busker on a kazoo, but whatever it is it can have no lyrics, for there are no words beyond these words that leave one speechless with dismay. As Bill Cheng writes, “They tell you, ‘You are where you deserve to be.’ But I know the way bad luck can build into streaks—a day, a week, a month, a year—all the avenues you thought were open shutting off one by one until all of a sudden you’re drunk and shaking and can’t see or hear for all your howling.” Here’s something they don’t talk about when the Buddhist Geeks talk the Singularity talk.

In his introduction to Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, Jose Barchilon paints a provocative, under-explored pre-asylum life — how Renaisance Europe dealt with the mad by placing them aboard narrenschiffen (ships of fools) and sailing them from port to port, where they’d alight for a few hours or days before returning on the ship and their onward journey into further unknown interiors. Foucault suggests a level of interactivity with and acceptance by the various townspeoples of the strange cargo. It was not so much a case of ‘there but for the grace of God go I’ as it was a tacit acknowledgement of the thin red line that separates madness and civilization.

The Mole People of New York may be fractured and ‘bent out of shape by society’s pliers’, as the Dylan tune goes, but even stripped down in the dark they maintain the dignity of matter and possess the integrity of atomic indestructability. Whereas everyone on the surface carries on as if they truly were the King of Prussia. And mightn’t a Fool just crack a smile, stepping off his ship in New York Harbor, and reading the lead piece in The Fait Divers Daily: “Swimming in the East River, Whitestone found a message in a bottle from the State Hospital on Ward’s Island. It read: ‘Some of us are sane’”?

Tales of Two Cities is, then, not merely about New York, per se, or about modern cities in decline, but more about the expanding cracks and fissures of civilization, the widening chasm between haves and have-nots that betokens, this time, an end to progressivism, to the notion that we’re all in this together, and a cruel, triumphant return to the feudal and industrial, as if Scrooge listened to other ghosts that fateful night and the next day informed Bob Cratchitt he’d have to reduce his hours to avoid Obamacare costs, leaving Tiny Tim without a leg to stand on. And all you could hear was the centrifugal force of a howling wind, and the lone cry for dignity.

John Kendall Hawkins is an American ex-pat freelancer based in Australia. He is a former reporter for The New Bedford Standard-Times.