If you’ve read anything about Paul Thomas Anderson’s newest film The Master, you’ve probably read a lot about how the movie is a thinly veiled biography of L. Ron Hubbard and the history the Church of Scientology and Dianetics. Then there are those who have expanded the interpretation of the film to include a vast range of weird religious cults that have infected America throughout history – everything from The First And Second Great Awakenings, to Transcendentalism, to snake handling Pentecostal Christians, to “est” and to believers in the Milton Bradley Company’s Ouji board which can be purchased at a store near you. Interestingly, missing from these interpretations of the film are references to religious cults gone bad and which ended in violence (e.g. People’s Temple, Waco Texas, Heaven’s Gate, etc.).

In retrospect, it makes sense that the more violent cults have not been referenced in relation to this film because in many ways The Master operates on multiple levels that move beyond the mere surface level of its subject. It is a film about American opportunism, sexual repression, and religious fervor, but it is also a movie about how Hollywood itself, of which Anderson is part, is its own kind of cult, selling its own brand of transcendental relief through the silver screen. Maybe movies don’t offer a way to reach heaven or the mystical realm of our past and future lives, but they do give us a place to lose ourselves for the duration of a film. If a director is as adept at manipulating the audience as Anderson is, then the films can even lure us into their doctrine against our will, not unlike the cult leaders he depicts in his films. Even if we read the film as an idiosyncratic vision of the history of whacky American religious cults and namely Scientology as depicted through Paul Thomas Anderson’s eyes, we have to remember that Scientology itself is woven into the Hollywood landscape in figures like Tom Cruise (who plays a cult leader in Anderson’s Magnolia and John Travolta). The news headlines constantly remind us of the connection between Hollywood and Scientology.

Cult leaders are no strange territory for Paul Thomas Anderson. In his first feature film Hard Eight (1996) Philip Baker Hall plays Sydney – a Patriarch Gambler and Cult Leader of Casinos who takes in the young, naïve and fucked up and teaches them “his way” to beat the system and line his pockets with cash. In Magnolia (1999), Anderson gives us the insanely obsessive and hilarious Tom Cruise (a literal Scientologist) who plays the leader of his own Cult of the Cock, a cult that teaches men to be men by “worshipping the cock and taming the cunt.” Already in this film, Anderson has merged whacky American religious obsession with sexual repression. He brings Hollywood into the picture with the figure of Jason Robarbs who plays Tom Cruise’s father and a major Hollywood producer and executive. In Boogie Nights (1997), Burt Reynolds plays a guru of porn, a cult leader in the film industry who brings young people into his fold and exploits them to support his “vision” and his bank account. Finally, in There Will Be Blood (2007), Daniel Day Lewis – a foreboding vision of megalomania—pares down American obsessive behavior and greed by connecting it to Western expansion, economic opportunism, and the oil industry. In this film, which precedes The Master, Anderson shows America’s tendency toward relentless pursuit of success devoid of human emotion and connection. Success itself is an artifice and god to which one dedicates his life.

As Anderson’s images of cult leaders and American obsession have progressed over time, his movies themselves have become more and more hyper-stylized and emotionally removed. In films like Hard Eight and his epic masterpiece of ensemble cinema Magnolia, we could find place for human identification, where we could ground ourselves in sincerity and emotional identification. Both movies provided moments of enormous emotional catharsis. But the more Anderson made films, the more the emotion became subverted by his own private style. The internal components of his films have become so private and so locked inside his own vision, that they resist emotional access from the audience. Yet, people like me continue to watch his work with the fervor and dedication of devoted followers. It could be that is Anderson’s point. He strips us of emotional identification, so we have no choice but to succumb to his vision just like we would to a cult leader, except that we’re watching movies and get to leave the theater when the film stops rolling.

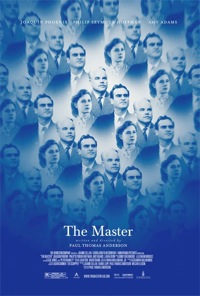

This brings me to The Master in which Philip Seymour Hoffman plays Lancaster Dodd (The Master and Founder of The Cause) and Joaquin Phoenix plays Freddie Quell (a fucked up veteran who becomes one of Dodd’s acolytes). The two actors play against each other with tremendous tension and energy. Both actors completely embody their characters – one showing his absolute obsession with power and control and the other physically embodying the inner torment of a war veteran and the emotional collateral he carries.

Much has been written about the acting performances (which are indeed superb) and the thread of Dianetics within the film, but very few critics have attempted to penetrate below the surface of the movie or analyze it at any depth other than commenting on its style, acting and historical references. One of the reasons so few people have attempted to dig below the surface of the acting and the overt subject matter is because the film intentionally resists analysis. Either what it has to say is written on the surface in its over-the-top performances and blatant reference to cult religions, or its subtext is deeply subverted by the intensely private vision of Paul Thomas Anderson. Like a cult leader, he resists penetration and doesn’t allow access to him or the interior of his film because that would make his “product” vulnerable.

From the onset, The Master is one of the tensest movies ever made. It immediately throws the audience into an uncomfortable state and then toys with the audience for the full 137 minutes of the film. It opens with Freddie Quell guzzling paint thinner or some other toxic concoction on the beach with a bunch of hyped-up and sexed-out soldiers wrestling on the shore in what is an overtly homoerotic war scene. If Jean Genet were to make a movie, it would have this scene in it. Freddie, however, does not engage in the Homo-Wrestling. Instead, he builds a naked woman out of sand, shoves his hand in her genitals, and then masturbates into the ocean, demonstrating his heterosexuality in the extreme. Freddie eventually passes out next to the giant naked sand woman with his head resting against her breast. If that is not a tense way to start a movie and make the audience immediately uncomfortable, then I don’t know what is. Certainly this opening scene does not allow any room for identification whatsoever. Joaquin Phoenix’s distorted and contorted body playing against the homoerotic wrestling scene on the beach, the glaring sun showing every drop of sweat and smudge of dirt on his twisted face, the close-focus askew camerawork – all of it is disorienting, unsettling, alienating and tense.

We then follow Freddie through various mumbled jumbled scenes in which he is fucked-up emotionally, wasted on his toxic drinks, and obsessed with sex. Freddie’s dialogue further alienates us. We can’t understand half of what Freddie is saying because he is so wasted emotionally,

physically and chemically. When he does open his mouth, it’s usually about pussy or cock. Freddie’s messed-up head and wartime trauma have led him to an addiction of drinking poison of his own concoction – cleaning fluids, kerosene, paint thinner, and who knows what else. In between he just wants pussy. While working the fields picking cabbages, he nearly kills a migrant worker with his poison booze. While the audience laughed at many of the opening sequences, it was uncomfortable laughter, the kind of laughter that says, “I have to laugh at this or run away.” There were those in the audience who chose the second option and walked out of the movie because this is a film that forces the audience to feel uncomfortable. Like a cult religion, it forces us to buy into its insanity or leave.

physically and chemically. When he does open his mouth, it’s usually about pussy or cock. Freddie’s messed-up head and wartime trauma have led him to an addiction of drinking poison of his own concoction – cleaning fluids, kerosene, paint thinner, and who knows what else. In between he just wants pussy. While working the fields picking cabbages, he nearly kills a migrant worker with his poison booze. While the audience laughed at many of the opening sequences, it was uncomfortable laughter, the kind of laughter that says, “I have to laugh at this or run away.” There were those in the audience who chose the second option and walked out of the movie because this is a film that forces the audience to feel uncomfortable. Like a cult religion, it forces us to buy into its insanity or leave.

Speaking of religious cults, Freddie eventually ends up on the run where he lands on the (borrowed) cruise ship of Lancaster Dodd. So begins the tense and dysfunctional relationship between Dodd, Freddie and Dodd’s wife Peggy (a truly bizarre performance by Amy Adams). Dodd falls for Freddie’s “poison” – his paint thinner home brew. Dodd can’t get enough of Freddie. He wants to convert him into his fold, and he wants to drink down Freddie’s poison. But really what Dodd falls for is Freddie in general. Much has been made of the “homoerotic nature” of Dodd and Freddie’s relationship and of the opposing acting styles and demeanors of Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix. I observed these two characters from a different standpoint.

Sure, Joaquin Phoenix’s performance of Freddie Quell portrays a man in enormous physical, emotional and psychic crisis. But that doesn’t mean Hoffman’s performance is one of austere purity like many reviewers have noted. When Anderson focuses on Lancaster Dodd’s face — with his day old stubble, his drunken and obsessive red face, his flaky skin and all the physical evidence of his toxic life – he is no pillar of cleanliness and stability. He looks as dirty and debauched as Freddie. In fact, he looks even more so. Dodd attempts to hide his debauchery behind his religious megalomania and The Cause. Freddie wears his dysfunctionality on the surface. As the movie plays on and Dodd seems to both want to heal and exploit Freddie, truly what is happening is that he is in love with Freddie.

In the meanwhile, Dodd’s wife Peggy stands by with her formidable presence and attempts to orchestrate The Cause from the sidelines. Amy Adams’ portrayal of Peggy is as disturbing as those of Hoffman and Phoenix. She is pregnant throughout the movie, an image of American domesticity and hetero stability, yet she does not exude wholesome feminine passivity; she is a portrait of menacing manipulation, spite, and control. Part of the way she orchestrates control takes place in a bathroom sink where Peggy gives Dodd a hand job while she stands there pregnant in her pajamas. When she finishes with “the job,” she wipes her hands on a towel and leaves the room. Surely, this scene is an uncomfortable moment for the audience. But, if you want to read below the surface, it’s Peggy’s way of handling (pun intended) Dodd’s homosexuality while also performing the role of the Public Wife so Dodd can sell his bizarre religious sham to the public. In American culture, you can’t be a religious cult leader and out of the closet!

The public, by the way, are a bunch of rich people who use Dodd and his bizarre melding of mysticism, eastern religion, and his own random thoughts for their entertainment. Dodd is just a fad. He is used by the rich people for entertainment much in the way that Dodd uses Freddie. Everyone is using someone in this movie, and in the eyes of the wealthy, Dodd is just a disposable fad who can be tossed away when he no longer suits their whims.

In the meanwhile, Freddie maintains his devotion to pussy to such a degree that when he attempts to go sober, he hallucinates that all the woman at one of Dodd’s revivals are naked. The camera cruises over every variety of pubic hair and boobs on women ages 17 – 70. At moments the camera holds still on close-ups of pubic hair or aging buttocks. In the meanwhile, the naked and pregnant Peggy looks out at us as a kind of dare. Yes, the uncomfortable moments are stacking up.

While much has been made about the homoerotic bonding between Dodd and Freddie, I beg to differ. This is a movie about opposing sides of sexuality in conflict and connection with each other. The issue at the core of the film is that Dodd is a repressed homosexual who is in love with Freddie, but Freddie is clearly entirely heterosexual to such a degree that his heterosexuality is seen as almost an aberration. Indeed Dodd calls Freddie “aberrated” when they first meet, but Dodd is the one with the aberration if we are to go by standard American social codes. The movie ends with Dodd professing his love for Freddie in song. Freddie turns his back on Dodd and walks away. He lands in a bar and has sex with some bar girl. Freddie plays “The Master” game with the girl, and she just laughs it off. In the end, Dodd’s hyper controlling mystical vision is nothing but one man’s attempt to control his own desires more than others.

The filmmaking style itself does not make the sexuality any more comfortable. Paul Thomas Anderson has become a bombastic, epic, filmmaker whose style is so extreme that even if the subject matter didn’t make the audience uncomfortable (for example in the scene when the pregnant Peggy talks about fucking with dildos) the filmmaking style itself pushes the audience to the brink of acceptable bounds between the filmmaker and the audience. It’s extremely artificial and staged while also closing in on uncomfortable aspects of human nature – the traits that we would rather ignore. So the filmmaking style with its austere, hyper-stylized, a-historical settings is as impenetrable as the characters.

Paul Thomas Anderson seems to have reached the point where he intentionally pushes all the buttons he can push and produces huge alienating idiosyncratic films just so he can test his audience’s commitment to his films. As a filmmaker who makes films that intentionally alienate the audience from emotion but then also seduce the audience into succumbing to their obsessive vision, Anderson is not unlike Lancaster Dodd or L. Ron Hubbard. Like these cult leaders, Anderson tests the followers of his totally unreasonable doctrine, and by testing them he lures them in and holds them captive to his vision. (At least for those who don’t walk out.)

I’m a pretty hardcore film geek and have a very high tolerance for oddness, excessiveness and insanity in films, but even I was overwhelmed by the tension of the The Master for the first hour or so. Finally, I realized that the only way I could “enjoy” this movie was to give myself into it entirely. I had to relinquish myself to its obsessive excessive vision just like I would give into a charismatic cult leader who is completely off his rocker yet somehow irresistible. I did give in, and I came out with lots of interesting thoughts about the movie. However, all my thoughts were really about how Paul Thomas Anderson manipulates the audience by making the audience feel tense, uncomfortable and then converted.

All that said, I remain dedicated to Anderson’s films. I think it’s interesting that when his films contained the most authentic human compassion and expanded their cinematic worlds and emotions to places outside of the insular vision of this 21st century auteur that he referred to himself simply as P.T. Anderson. But the more and more insular, idiosyncratic and alienating his films became, he expanded his name to the complete Paul Thomas Anderson a name as long, wide and expansive as the 70 mm film he uses to record his compulsive visions. I guess that’s Anderson’s point in this movie more than anything. He is Lancaster Dodd, and he won me over again.

Kim Nicolini is an artist, poet and cultural critic living in Tucson, Arizona. Her writing has appeared in Bad Subjects, Punk Planet, Souciant, La Furia Umana, and The Berkeley Poetry Review. She recently published her first book, Mapping the Inside Out, in conjunction with a solo gallery show by the same name. She can be reached at knicolini@gmail.com.