My family really enjoyed the new Netflix period drama Bridgerton, a kind of technicolor Jane Austen pastiche soap opera which was great fun to watch. Like Austen’s novels, it is set at the beginning of the 1800s in England during the Napoleonic wars. And like Austen it centers entirely around marriage, this time the on-off romance between Daphne Bridgerton and the Duke of Hastings. The events move from one glamourous ball to the next, with lots of heartache in between.

Daphne’s family are well off but her father died, and she is the eldest of three sisters and two brothers. Securing a good marriage is important for her future, but she also wants to marry for love.

A number of inequality experts, including Branko Milanovic and Thomas Piketty, have drawn on Jane Austen’s work as it is a very precise description of life in the 1% and the 0.1% at that time in history. She gives very precise accounts of different levels of economic income and what that entails.

During the time of Austen, the value of money was very stable. The average income remained around £30 a year for nearly a century. For Austen, in order to live a life that was elegant and comfortable, with servants and money for books and amusements, an income of around 20 to 30 times that was required, or around 500 to 1,000 pounds a year (US$683 to US$1367).

In the UK at that time, British aristocracy was about 25,000 people, which was the top 1% of society at the time. They were a class of prosperous property owners. Within this number were the even richer nobles (lords, barons, and knights) numbered around 1,500. Needless to say, this was a very unequal time.

They were living during the transition from an ancient society of nobles and peasants to the beginnings of modern capitalism based on a regime of property ownership — something Piketty writes about at length in his new book, Capital and Ideology.

The first thing to note about these times is that none of the rich people have got rich through working. It is not possible to have the kind of wealth described by Austen and in Bridgerton through a profession. It is only possible by having enough property that you can live comfortably off the interest from that property. The primary way to get rich was to either be born rich or marry someone rich.

Historically this property had been primarily land, and the rents derived from that land. At that time, the annual income from capital was a reliable 5 percent, so you needed capital that was worth about 20 times its annual yield. So an income of 10,000 pounds would require a capital of 200,000 pounds.

While rents from land remained a key source of income, capital portfolios were already becoming more and more diversified. In Austen’s novel Mansfield Park, one of the characters must go to the Dutch Antilles for a year to tend to his plantations. Austen makes no mention at all of slavery, which was its peak at this moment in history. The country was also prosecuting a lengthy and expensive war against Napoleon and financed this in large part by borrowing from the rich.

There is actually a brief moment in Bridgerton when real life intervenes. The local peasants tell Daphne (spoiler alert), now Duchess of Hastings, that their rent has increased and they are facing hardship. The Duke is horrified by this news and spends a couple of days actually working at doing some paperwork as a result. This seems to fix the problem, before he gets bored and the plot moves back to the bedroom.

But generally, these messy real-world events barely make a dent on Austen’s and Bridgeton’s world of Lords and Ladies. Through the miracle of property and ownership it is all transformed into a sanitized and secure income that allows a life of leisure.

In the modern world, the gradations of rich are billionaires, ultra-high net worth individuals (definition varies but generally those with over $30 million in assets), and high net worth individuals (again, definition varies, but those with at least $1 million in investable assets).

The UK, for example, has around 14,000 people who are ultra-high net worth and many more who are high net worth. While ordinary savers are having to cope with negative interest rates, stock markets are booming and the super-rich in today’s world could certainly expect the same rate of return as in the time of Austen, around 5 percent.

So a member of the ultra-high net worth class in the UK would expect a minimum annual income of around £1.5 million, which should allow them to live comfortably with enough books and other entertainments.

Thomas Piketty’s main contention in his most famous book, Capital, is that we are gradually returning to an age where inherited wealth and the returns from income on property will become more and more important.

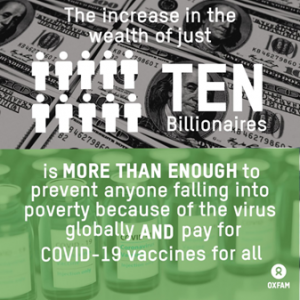

Despite the chaos of Covid-19 and the economic catastrophe that it has caused, the fortunes of the super-rich have bounced back already and continue to grow. Oxfam has just released its annual report tied to the World Economic Forum, the gathering of global elites that usually takes place in tony Davos, Switzerland, but was moved online this year.

Inequality Virus reveals that billionaire fortunes took just eight months to return to their pre-crisis highs, and the richest 10 men have seen their fortunes increase by a staggering half a trillion dollars. Meanwhile it could take 10 years at least for the numbers of people in poverty to return to their pre-crisis levels. Maybe people will look back on Covid-19 as a moment that accelerated the return to a hyper-unequal patrimonial society of the super-rich.

Maybe also in years to come there will be period dramas starring characters based on people like Kim Kardashian, who organized her elaborate 40th birthday party in October last year on a private island while her compatriots faced lockdown, death, and destitution. She was apparently humbled by her privilege at least, which was good to hear.

Photo by Kim Kardashian West.

For now, a second season of Bridgerton has been commissioned, which is great news and will be very popular in our house.