To drive out of Ithaca in the cruel showers of this April you need a soundtrack.

Once you’ve left the citadel of Cornell University and its outlying fiefdoms of sport and agriculture, the countryside hosts trailer parks, weather-beaten houses, junked machinery, and prisons. There is little suggestion of spring, patches of snow still lurking on the banks of swollen rivers and amonst the barren trees. With the a new shroud of leaves not yet unfurled, human poverty confronts the motorist at nearly every turn on the way to the New York City, beginning with rural route NY 79 heading southwest towards to the closest Interstate, I-81, then traversing Pennsylvania before hooking up with I-80 for the final more affluent stretch across New Jersey and into Manhattan.

The towns along the way are devoid of commerce except for gas stations. The former downtowns of post-industrial cities like Binghamton look like they’ve been hosting a civil war: derelict buildings and boarded-up shop fronts alternate with bombed out parking lots. Residents seek refuge in the ailing malls. Prayer appears necessary: from behind the windshield, it would seem that only a miracle will make America great again.

Coming down from the Endless Mountains in northeastern Pennsylvania civilization emerges in the form of Scranton, a place that has attained an unexpected fame—or perhaps infamy—first as the setting for the American version of the television series The Office, and then as the hometown of Joe Biden. Though I can’t claim an intimate knowledge of its civic glories, Scranton seems to be amalgam of malls, slag heaps, and pork-barrel highway projects. Most striking, however, is the landmark spread across the first hills of the Poconos rising up from the city’s southern edge. This could well be the world’s largest junkyard, a vast “parking lot of the dead” as James Dickey put it in his immortal “Cherrylog Road,” though Scranton’s sprawling acres of wreckage hardly seem a compelling place for an erotic encounter.

After the Poconos it’s Delaware Water Gap and then the ever-encroaching sprawl of New Jersey all the way to the Hudson.

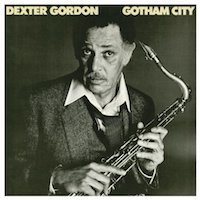

I’ve brought along a random assortment of CDs snatched from my largely  unorganized shelves and thrown the discs into a canvas bag. I reach in and randomly pull out Dexter Gordon’s Gotham City.

unorganized shelves and thrown the discs into a canvas bag. I reach in and randomly pull out Dexter Gordon’s Gotham City.

It’s been about a decade since I’ve listened to this recording. Strange that I haven’t even missed it until now. Great music stays with you until the final erasure, be it slow or sudden, of the personal hard drive.

That I own about half of Dexter’s recorded output isn’t much of collector’s boast, since he spent too much of the 1950s, which would have been one of his most productive decades, in and out of jail for heroin possession, his final release from Folsom coming in 1959. Still, he made more than fifty recordings after his years in the big bands of Lionel Hampton, Louis Armstrong, and Billy Eckstine in the 1940s.

I can’t say exactly why Gotham City, scandalously out of print, holds a special place in my affections, but it does. Yes, there are the dates of thrilling tenor madness with Wardell Gray, and some boisterous sets for Savoy in the mid-40s; also the gleaming monument, “Daddy Plays the Horn”, made in 1955 just before Dexter did a five-year stretch at Riker’s Island penitentiary. Then there is the Blue Note series started before Dexter left to go play a month-long gig at Ronnie Scott’s London jazz club in 1962 (a trip that turned into fourteen years of expatriation in Europe), and continued on occasional trips back to the U.S. There are also the radio broadcasts (issued on Steeplechase) and films from the Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen, the city where Dexter lived for over ten years and which cherished his presence as America never would. There are also the early 70s sessions done back in the U.S.; I would single out “The Jumping Blues” of 1970, if only because it has Wynton Kelly on piano). These were soon followed by Dexter’s return to this country in 1976, an event commemorated in Homecoming: Live at the Village Vanguard , featuring trumpeter Woody Shaw’s marvelous quartet, with Ronnie Matthews making the Vanguard’s out-of-tune piano jump).

Notable monuments of Dexter’s repatriated years are Great Encounters with saxophonist friend Johnny Griffin (“fastest tenor in the West”) in concert at Carnegie Hall, and the live recording from Keystone Korner in Oakland with Dexter’s stellar quartet from the late 70s—George Cables on piano, Rufus Reid on bass, and Eddie Gladden on drums. I’ll admit that I’m not so enthusiastic, though still duly reverential, about the soundtrack for Round Midnight, the role for which Dexter received a Best Actor Academy Award nomination in 1985.

But for today it’s Gotham City on the way to Gotham. The bleak landscape looks different as soon as I hear guitarist George Benson’s eight-bar introduction to “Hi-Fly” by Randy Weston. Benson is much better known for his pop hits as a singer; his “Give Me the Night” was released the same year as Gotham City in 1980, and four after he made it to number one on the pop charts with his album “Breezin’” and “This Masquerade.” At the time of Dexter’s Gotham session, the pop music money and stardom had done nothing to blunt Benson’s genius for jazz.

At the close of Benson’s introductory choruses to the album’s title track—a seemingly nonchalant blues that, over its ten-minute course, will build to a pitch of fantastical, yet always poised exuberance—there a volcanic drumroll that can only be the work of Art Blakey, reunited on record with Dexter for the first time since 1944 when they were both members of Billy Eckstine’s Big Band, that traveling crucible of bebop. The long arms of Blakey’s drumming embrace all that enter the tent of his big beat, welcoming them with the ebullient counter-rhythms of his left hand and feet, the mighty crescendo of his right hand on the ride cymbal, electrifying the musical space like ionized steam.

Dexter enters with warm-hearted noblesse oblige, lagging far behind Blakey’s beat with aristocratic surety. This refined confidence will be in evidence both in swinging affairs and when he enjoys the album’s lone ballad, “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.” The tallest tenor, Dexter is never in a hurry even at fast tempos like that of “Blues March,” where he’s joined by trumpeter Woody Shaw, whose angular, harmonically displaced lines spark like syncopated ricochets.

What I love so much about Dexter’s playing, something that finds such glorious expression throughout Gotham City, is the balance of the expected with the unexpected. When Dexter shows you around his enormous musical estate, you never go quite the same way; it is the unexpected turns of path through a familiar landscape and his knowing asides that make the tour so enjoyable. When embarking on a Dexter solo you know you will hear certain quotations and other favorite figures, but never in precisely the way you’ve heard them before.

It is also the way these formulae are put together that is so compelling. Each improvised motif seems both the answer to the preceding phrase and the question demanding the next response. The architecture of Dexter’s solos is constructed from these units, whose meanings range from the lofty to the ironic to the farcical. Many of these building blocks are quarried from his own music and from pop, folk, and children’s songs. These motives are deployed with particular deftness on the album, as when his signature quotation of “Mona Lisa,” modulates onto itself across the boundary dividing two stanzas of “Hi-Fly.”

There are those who might say that Dexter’s use of stock phrases is overly schematic, while others might claim that in signposting his improvisations in this way Dexter offers a critique of the art of improvisation itself, ironically laying bare the mechanics of his craft. The great orators of antiquity built up their speeches with well-known rhetorical figures, stock phrases; it was the way in which they manipulated these figures that made their reputations and moved their audiences. Dexter is the Cicero of the saxophone.

Dexter’s inventive largesse has its effect on his sidemen. Benson’s solos are much more than prodigious technical demonstrations, filled with multi-directional arpeggios, virtuosic melodic configurations, rapid bursts of octaves, and a frenetic chordal arrays. The way he complements Cedar Walton’s incisive piano contributions with complex rhythmic commentary seems the perfect solution to the problem of having two chord-playing instruments playing behind a soloist.

It seems hard to deny that it is Blakey’s aegis that inspires his rhythm section colleagues to such great deeds. After Dexter takes his final chorus on “Gotham City,”Blakey starts right off on Benson’s solo with a quick pair of rim clicks on the fourth beat of every other measure. Walton notes this pattern and begins playing off of it. The dialogue here is fierce. Percy Heath’s bass is the grease in that groove, and though thick it’s just this side of combustion.

By the second chorus Blakey is pushing into the ride cymbal on the fourth beat of those measures not given over to rim clicks, momentarily suspending the swing, so that there is a short, shimmering pause in forward momentum. Walton quickly perceives this additional layer of complexity and there is spirited conversation between him and his former Jazz Messenger employer, Blakey. They enjoy a second chorus combining these contrasting inflections of the fourth beat with bassist Heath joining in for its final utterance. Once agreed upon by the entire ensemble, the motif is just as quickly dispersed by the counterpoint of individual intentions. A great band knows when to disband a musical idea and move on. In this passage the dialectic between the ensemble and its members—perhaps the greatest contribution of jazz—reaches perfect and unforgettable synthesis.

I’ve assembled my traveling companions for the drive south through Binghamton, Scranton, Stroudsburg and then east towards New York.

There can’t be more than forty minutes of music on Gotham City, two tunes per side on the old LP. I get Gotham ten times back-to-back before the Empire State building rises above the New Jersey traffic. And then there’s the trip back Upstate.