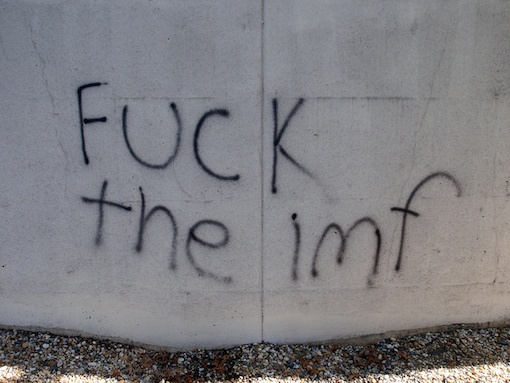

Photo by Daniel Lobo | CC BY 2.0

I was taken by surprise by the headline of the Latin American Herald Tribune: Global Elites Insist on Greater Trade Openness to Halt Populism. The article reports on the IMF general assembly held in Washington over the weekend and it shows just how disconcerted the “global elites” are by the rising tide of disenchantment with the neoliberal gospel not only in the Global South, but in the Center (Europe and the United States) as well. But why all the worry? I thought history ended in 1989, the progressive cycle is now ending in Latin America, and globalization was the fulfillment of the World Spirit.

The headline suggestions that the “global elites” are grappling with what appears to be a contradiction. If “populism” (a term that is probably being used here in a pejorative way) itself is anti-free trade, how can more free trade cure the disease that provokes anti-neoliberal populism?

The article quotes IMF head, Christine Lagarde about her prescription for the “mediocre” world economy that is causing the populist disaffection:

“The first priority for inclusive growth is to escape the ‘new mediocre’ of low growth, low employment, and low wages. That means using all policy tools – monetary, fiscal, and structural: to maximize the synergies within countries – and amplify the impact though coordination across countries.”

Of course, “all policy tools” likely refers here to those tools acceptable to the IMF, not the ones employed by those sovereign nations experimenting with other economic models.

With regard to whatever “populism” might mean here, the IMF statements point not only to the critical consensus of millions of persons in the Global South (the periphery if you like), but also to a growing dissident movement in some of the Global Center countries.

The article does not mention that though the “global elites” are using “all the [neoliberal] policy tools” in Argentina, the “adjustments” that have triggered rising unemployment and a pull back in social investment are causing a growing popular backlash there; and in the aftermath of the institutional coup against President Dilma Rousseff, Brazil is next in line.

To make things worse, the Brexit, says the Herald, “has caused alarm bells to ring in world financial centers.” And that’s not all. “Officials expressed a marked concern for the mistrust of the benefits of global trade evidenced in the presidential election campaign in the United States, the world’s largest economy.”

Yes, the U.S. is the world’s largest economy, but it is worth adding that the US is also among the “developed” world’s most unequal economies with poverty hitting minorities the hardest and more people in jail than any nation on earth. The antipathy to free trade by the electorate is so pronounced, even Hillary Clinton is willing to throw the Trans Pacific Partnership under the bus ( at least for the next four weeks).

The IMF prescription to treat the disease of the inequality generated by the private accumulation of socially produced wealth is more neoliberalism. But this won’t come easy. Since “populism” can often compete effectively at the ballot box, the “insistence” of the use of adjustment-medicine may require a measure of “arm twisting” (to borrow a term from President Obama) with regard to those nations or political parties that do not know what is good for them.

The headline and article suggest that “populism” poses a challenge to the agenda of the “global elites.” The Herald concludes “it is perhaps for that reason that the IMF has expanded the focus of its analysis, which has been traditionally focused on macroeconomic stability and growth, to include calls for the need to fight economic inequality and the negative consequences of globalization.”

Those negative consequences of globalization, however, are arguably not mere accidents, but an essential feature of the capital system.