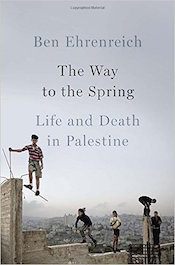

Ben Ehrenreich, an American journalist with an eye for the ironic an ear for the perfect succinct phrase, has created pictures of both village and town life of Palestine under the occupation, behind the Apartheid Wall, and inner walls. “The Way to the Spring” begins in 2011, when the author first visited Nabi Saleh to report on the village protests for the New York Times Magazine, and ends in the fall of 2014, following Israel’s Operation Protective Edge in the Gaza Strip that summer. Ehrenreich lived in the West Bank intermittently between 2011 and 2014, absorbing the world of Palestine, so different from Los Angeles, his home base. He starts small: a village, a surrounded house, a Friday protest.

Since the occupation is about containing people, taking their land, draining their wells, destroying their cultural sites, The Israeli government speaks through different kinds of walls, permanent checkpoints, and flying checks. Ehrenreich shows his reader the physical walls, but further, the subtleties of verbal walls and the walls of armed IDF soldiers and Border police who keep Palestinians out of reach of hospitals, businesses, cultural centers, and even the holy places in Jerusalem and the West Bank.

First, and most obvious, the Separation Wall, called by Palestinian activists the Apartheid Wall. The average height of the Berlin Wall was 11.8 feet, whereas the current height of Israel’s Wall is more than twice as high: 25 feet. One of the joys of this book is that the author does not spend his time reviewing readily available material. Copious endnotes will lead the interested reader to the thickness of scholarship they crave. Clearly anyone attracted to a 400-page book about the occupation in Palestine has heard plenty about the Apartheid Wall and has read in our mainstream media about the struggles, mostly from a Zionist “it’s our right” insistence for years. So the author moves in for tight shots, intimate conversations, small villages that are getting smaller as the illegal settlements swell in size. He is so successful that since finishing this memorable account, I have been wishing I could be in contact with the families from Nabi Saleh and Umm al-Kheir. Are they safe? Who is in Jail and who got out? Is everyone too exhausted to protest every Friday at the Spring?

In his Introduction to The Way to the Spring: Life And Death of Palestine, Ben Ehrenreich makes his intention quite clear. ”I do not aspire in these pages to objectivity. I don’t believe it to be a virtue, or even a possibility.” He considers his work “a collection of stories about resistance, and about people who resist.” I would caution that his use of the word story does not mean the conventional beginning, middle and end. These are stories stuffed with middles, down to the most microscopic detail. By the final chapter we cringe at the tragedy of Palestine: there is no resolution, not one offered even by this astute observer. The burdens of life continue as they did in the beginning of the book, only the hardships proceed at a faster pace. More Palestinians are arrested, more are shot, more are killed.

Ehrenreich takes the reader to view smaller “personal” walls that enclose one or two houses. These “surrounded houses” are being more frequent in the towns of the West Bank. The first one I saw was in Bethlehem in 2006. The owner had painted his dwelling bright red. I can still visualize that small red house standing out from the dun-colored stones and cement wall that surrounded his life. Ehrenreich finds a similar house and recounts his visits with Hani Amer and his family rather than dwelling upon the usual journalistic reportage about  resistance. Amer’s story is recounted so vividly that those readers who have never been to the West Bank will understand the hour-by-hour hardship of daily life after their visit with Amer. The farmer has lost two-thirds of the land surrounding his house as well as five acres on the other side of the barbed wire fence. He can see his land, but he cannot farm it. To protect the incoming horde of illegal settlers, the Israelis built a wall around Amer’s house, well within the Green Line, the internationally recognized border between Israel and the Occupied Territories (oPt). Rarely discussed openly is the underlying intention of the Occupying power that the maze of walls and checkpoints are the prelude to Israel’s pursuit of all the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. The only negotiation Amer was able to make with his captors was that that he could have a key to the locked gate, which he triumphantly painted bright yellow. By the time Ehrenreich arrives at the surrounded house, Amer has planted vegetables, all kinds of fruit trees, even herbs such as the essential Palestinian za’atar. This tough middle-aged Palestinian farmer tells the American journalist, “Instead of seeing the wall, I try to see the garden.”

resistance. Amer’s story is recounted so vividly that those readers who have never been to the West Bank will understand the hour-by-hour hardship of daily life after their visit with Amer. The farmer has lost two-thirds of the land surrounding his house as well as five acres on the other side of the barbed wire fence. He can see his land, but he cannot farm it. To protect the incoming horde of illegal settlers, the Israelis built a wall around Amer’s house, well within the Green Line, the internationally recognized border between Israel and the Occupied Territories (oPt). Rarely discussed openly is the underlying intention of the Occupying power that the maze of walls and checkpoints are the prelude to Israel’s pursuit of all the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. The only negotiation Amer was able to make with his captors was that that he could have a key to the locked gate, which he triumphantly painted bright yellow. By the time Ehrenreich arrives at the surrounded house, Amer has planted vegetables, all kinds of fruit trees, even herbs such as the essential Palestinian za’atar. This tough middle-aged Palestinian farmer tells the American journalist, “Instead of seeing the wall, I try to see the garden.”

Ehrenreich weaves the story of the Tamimi family into many of the accounts in the book. He has the novelist’s ear for dialogue so that the reader hears the hopeful voice of the peace activist Bassem Tamimi that the protests have meaning, “Our spring is the face of the occupation,” he tells his friend Ben as they walk through the village of Nabi Saleh. Every Friday the villagers, joined by international and Jewish solidarity activists, march toward the spring in an act of protest. “And every Friday Israeli soldiers beat them back with tear gas, stun grenades, and rubber-coated bullets,” Ben observes. Afterward, groups of male teenagers standing some distance away from the adults, hurl stones at the soldiers, who are beyond the reach of their weapons. It seems unnecessary to point out that stones hurled by children are no match for tear-gas canisters and bullets. After months of watching stone throwers rarely hitting their mark, Ehrenreich wonders if they have ever been successful. He contacted the IDF about the results of Palestinian stone-throwing activities, and the IDF confirmed that they have no records of any Israeli solder ever being killed from a stone-throwing incident.

As the months go by, Ehrenreich sketches the weariness that has encompassed Bassem. His children and their friends flock to protests knowing that their homes are no safer than a confrontation line, particularly after Israeli shellfire kill one child in his bedroom months. The protests become darker. Protesters endure prison and torture. They come home. They are beaten. Some survive. Bassem has been in prison for almost a year, for being a leader of the protests. The Israeli military courts seem not to know that according to international law peaceful protests of an occupied people are legal.

As fewer Palestinians attend the Friday protests, our American journalist acquires the gritty feeling most of us experience when spending more than a month or two in the West Bank. He has watched Palestinian friends carted off to jail. He has inhaled tear gas at the Friday protests. He is tired of the checkpoints and the IDF soldiers half his age. Trying to strike up a conversation with an IDF soldier in Hebron turns into “grunts and commands,” neither of which being out the best in me,” he writes. Another year passes. Ehrenreich is having coffee with a young Israeli soldier in Jerusalem, an area not so tension-filled as the West Bank. The young soldier does not question what his superiors have taught him. “If you see a Palestinian with a knife, you shoot him,” he says as though quoting from the manual. “And if you see a settler with a knife?” Ehrenreich asks. “You do not touch a settler,” the young soldier replies slowly.

The book ends as it began. The Israelis continue to swallow more Palestinian land. More people are in prison. The world seems indifferent. Hope comes from those who counter the propaganda that the Zionists diligently manufacture on Twitter, Facebook, and online journals. The deepest consolation is to be found in the books like “The Way to the Spring.” Without melodrama and pathos, Ehrenreich has provided a literary map to the struggle for Palestine. It is almost impossible to wonder on a Friday is the marchers will get to the spring this week.

In closing, I must recognize reactions to this book by some reviewers and within social media. In a number of reviews Ehrenreich has been accused of not analyzing Palestinian terrorism, a word that seems overstated in relation to the daily horrors that Palestinians face. A few suicide bombers, whose activities always make the US mainstream news, are not part of his project. He could not interview them. Reviewers and angry readers have tried to reshape the discourse, reminding us that Jews are the victimized, the ones we must embrace. Assuming the author is Jewish, one gentleman writes on Facebook, “You are a disgrace to the Jewish people. We have enough haters from outside, we do not need one from within.“ Ehrenreich is not Jewish, and he is not writing the book the Facebook guy wants to read, the one that justifies Israeli military actions since the Nakba in 1948. This is not the book that connects the German Holocaust with the fate of Arabs in their homeland. Trying to explain his viewpoint to an interviewer, Ehrenreich says with not so subtle irony, “across the street from the Israeli settlement Beit Hadassah – I saw the words Gas the Arabs spray-painted in English on a wall. I do not think I need to explain why that was so upsetting.”

Fiery reactions to this book have puzzled me. Some reviewers and the angry pro-Zionist social media refuse to acknowledge what Ehrenreich has made explicit: this book is written from the perspective of Palestinians in the towns of Ramallah and Hebron, the village of Nabi Saleh, and the Bedouin village Umm al-Kheir in the south Hebron hills. The author has written the book he wanted to write, not the one that would be easier to read.

In the weeks since publication, Ehrenreich has spoken of the verbal stones that have been thrown at him, mostly through social media. “I was called a Jew-hater times than I can count, as well as a terrorist and a murderer. It was suggested to me that I should, and may, suffer a terrorist attack. I was told that ‘sick, twisted people’ like me ‘should not be allowed to write’ and informed that I will someday answer for the acts of I terror I allegedly support. I was wished a painful death and promised that I will ‘get what is coming to me.’” Most of us who are openly pro-Palestinian and fight for the end of the occupation have been threatened, but rarely so vividly. As an academic, I have been accused of frightening Jewish students in my classes and been given the cold shoulder by colleagues. But I have never been wished a painful death –as far as I know.

Reflecting on his extended time in the West Bank, Ehrenreich knows that it wasn’t all sadness. People laughed a lot. Or perhaps sadness has many faces and laughter is one of them. Palestinians have been carrying the burden of the Zionist illegal occupation for more than half a century. Grief is not special. Year after year Palestinians experience waves of greater and lesser sorrows, but sorrow is always with them. Ben Ehrenreich carries the sorrow too. But he also is amazed “by the grace with which people deal with and struggle against these hardships in their daily lives.”