Less than two weeks in Iran does not make me an Iranian expert or even a seasoned Persian diplomatic hand, but it is more time than nearly all the members of Congress have spent collectively in the country that they chose to revile in celebrating, repeatedly, the speech that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered before the joint session on Capitol Hill.

As best as I can determine the only current or former American lawmaker to visit the Islamic Republic since 1979 is former Representative Jim Slattery (D-Kansas), who went there to a conference in winter 2015. He said of the continuing negotiations to freeze Iran’s nuclear weapons capabilities, “They are very troubled by the prospect of … putting their best deal on the table, only to have US lawmakers reject it.”

Iranian negotiators who watched Netanyahu barnstorm across Washington and the Capitol can have little doubt that any Iranian-American treaty on nuclear arms that is submitted to the Republican majorities in Congress will suffer the recent fate of President Obama—that of marginalization in the call to arms against Iran.

As defined by Netanyahu and ratified by the Congress—at least in a series of standing ovations—Iran is a terrorist nation that is determined to develop a nuclear capability for possible use against Israel.

Implicit in the prime minister’s remarks is the inference that if the United States negotiates a “bad deal” with Iran, Israel will have little choice but unilaterally to take out the Iranian nuclear capability.

By giving Netanyahu a joint session of Congress to draw lines in the sand, the Republican majority was extending its approval of a such a preemptive strike, perhaps figuring that smoldering mountainsides in Iran will make for excellent 30-second outtakes in the next election.

Despite traveling to many corners of Iran—using trains and buses, going where I pleased, and paying my own way—I have no privy knowledge of its nuclear intentions nor its plutonium capabilities. Nevertheless, I did see the country on the ground, and the impression that it left is that of a nation that would serve best as an American ally rather than as an enemy.

The bright lights of the holy shrine at Qom. The city, home to many mullahs, also is where many non-government councils oversee the Iranian Parliament, which meets in Tehran.

Iran is Persian and Shiite, not Arab and Sunni, and most of its foreign policy tensions are with nearby Gulf states, Afghanistan, Sunni regimes, Azerbaijan, and Russia. Saddam’s Iraq—with chemical weapons—attacked Iran for eight years in the 1980s. America might be a global power, but it lies over the horizon, and in my travels no one mentioned the name Obama.

During the 1979 revolution of Ayatollah Khomeini, the specter of the United States played a useful role as the Great Satan, which had propped up the deposed Shah after, in 1953, it took down the government of Mohammad Mossadegh, who had nationalized Western oil concessions.

These events took place before most Iranians were born, and even the former U.S. embassy, where the hostages were held, looks no more evil than a Rustbelt warehouse, despite the best efforts of Hollywood’s CIA bromance, Argo.

However out of date, the phantoms of Islamic-fascism contrast well with American storyboards that depict Israel as a beacon of democracy in a sea of fundamental extremism. No wonder Congress heard most of the Netanyahu speech on its feet or knees.

Seen up close, Iran turns less on its axis of evil, and looks more like a post-imperial society that is trying to make its way in a world where it has few, if any, friends and an isolated economy.

The American hostage-takers from 1979, possibly including former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, have largely departed the political scene, much as Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is in the dotage of his Supreme Leadership.

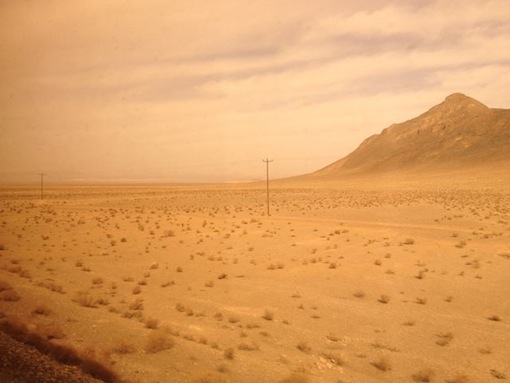

Tabas Desert: near where the American military landed its forces in a failed attempt to rescue the American hostages in Tehran, 1980.

To be sure, the Supreme Cultural Revolution Council vets candidates for federal offices and can veto any liberal initiatives of President Hassan Rouhani, just as operatives in the Revolutionary Guards can still ship car bombs to Hezbollah or missiles to Assad.

Nevertheless, younger Iranians see no more purpose in such state-sponsored terrorism than do their counterparts in the United States (or Israel, for that matter) who want nothing to do with remote drone killings and undeclared wars in places like Iraq and Yemen.

In the course of my travels, I went to all the important religious shrines in Iran—notably those in Mashad and Qom—but in no way would I describe those I saw at prayer as “fanatics.”

In the Western press, Qom is full of hard-core clerics flagellating themselves or calling for the deaths of Americans or Jews. Closer to the ground, Qom is Allah’s Asbury Park, complete with gift shops, cruising teenagers, blinking lights, and, inside the shrine, mullahs on their cell phones and small boys kicking soccer balls.

I have been to mosques in Pakistan, Syria, Turkey, and Egypt, and by the far the most tranquil are those in Iran.

Nor in my experience do Iranians hate Americans, despite the legacies of economic sanctions, military incursions, coups, and support for the Shah’s kleptocracy.

In my travels, when the subject of America came up (which wasn’t often), Iranians expressed the view the few Americans bothered to come to Iran, and knew little about its culture (a Persian civilization more than 2500 years old), its religion (Shia Islam), its politics (nominally a republic, which is more than you can say for most countries in the Middle East), or its foreign policies (in which suspicions about the U.S. and Israel are far down the list of preoccupations).

Nor did I come away from Iran thinking that it has designs to become a regional hegemon. Not even in southern Iraq, with its Shiite majority, is Iran especially interested in annexing those lost provinces of Persia.

Yes, Iran is a patron of Hezbollah and occasionally Hamas and the Palestinians, and a shadow player in the civil wars of Lebanon and Syria. So too is Israel (which has invaded Lebanon and bombed Syria repeatedly) and the United States (which at last count has dropped bombs on or sent forces into seven countries around the Middle East).

Keep in mind, too, that neighboring powers with atomic weapons include Pakistan, Russia, China, Turkey (from NATO), India, and Israel, which, unlike Iran, is not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The irony of American and European economic sanctions against Iran is that they hurt everyone—the banks, merchants in the bazaar, local companies, tour operators, etc.—except those they were designed to influence, the mullahs, who cling to power on allusions to Great Satanism.

Where the sanctions bite the hardest: in the bazaar and among tour companies. Here, the grand bazaar of Tehran.

Do I think the United States and Iran can reconcile their differences? I am not optimistic, if only because both sides have little sense of the other, and not much enthusiasm for shaking loose their shrouds of ignorance.

Few if any of the clerics who oversee Iran’s parliament and president have been to the United States since 1979, and it remains a caricature of the evil empire that funds the repression of the Palestinians, decadent Saudi princes, and reactionary regimes from Egypt to Afghanistan.

To the flag-waving, Netanyahu-loving Congressional echo chamber, Iran is just another Middle East tyranny intent on wiping Israel off the map or a state sponsor of terror.

That the United States—independent of what Israel might want—could embrace the republican ideals in Iran (distant as they might be today) or that Iran could find value in American innovation, investment and ideals, unfortunately, remains a remote possibility.

Such is the tenuous grip of the Islamic revolution on the populace (most Iranians are not particularly religious, by my observation) that it needs Israel and the United State as “good, safe menaces” for domestic political consumption.

Similarly, Netanyahu and his disciples in Congress—thinking of their own reelection campaigns—need to believe that Iran is a vast Nuremberg rally, just waiting for the chance to drop the big one on Israel.

When you get there, Iran appears more as a struggling developing country—with serious problems of urbanization, economic instability, infrastructure, and inflation.

Shrine of Imam Reza, Mashad, eastern Iran: among the holiest sites of the Shiites. Nevertheless, all visitors are welcome to enter.

Left out of Netanyahu’s descriptions of Iran—mind you, he’s never been there either—is anything resembling what I experienced in my travels. I never came upon any armed police, troubles in the street, intolerance, nativism, or extreme nationalism.

Ironically, there is a sense of calm about Iran and Iranians. About the only visible legacies of the revolution are the omnipresent billboard images of ayatollahs Khomeini and Khamenei, and women swathed by the hijab.

My enduring images are of the hundreds of well-dressed, cheerful and well-mannered school children, with whom I was traveling on trains between sites of Persian glory. Invariably they spoke some English and were fascinated with the foreigner, often asking if they could have a picture taken with me.

Their proud parents, equally well-dressed, would meet them at the stations, usually with a single red rose. I could be wrong, but they looked like kids who will grow up to become accountants, dentists, and professors, not holy warriors.

All photographs by Matthew Stevenson.

Matthew Stevenson, a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine, is the author of Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited Whistle-Stopping America. He has just returned from Iran.